Gilbert White: The naturalist whose poetic but precise words changed how we see the world

The writings of churchman and naturalist Gilbert White are as beautifully exquisite as they are scientifically precise. 300 years from his birth and John Lewis-Stempel

"If people that live in the country would take a little pains, daily observations might be made with respect to animals, and particularly regarding their actions and economy, which are the life and soul of natural history" — Gilbert White, May 12, 1770

In the beginning was the word, and the word was that of the Rev Gilbert White. Ur-naturalist. Prophet of ecology. Creator, with the publication of his The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, of Nature writing. The gifts of White, born 300 years ago on July 18, were his own, but any biographer, in book or in article, must give thanks to the Church of England; the stipend for serving up a Sunday sermon supported the life of White’s other devotion, Nature study. He was the exemplar of that now extinct species, the English parson-naturalist.

Following a career at Oxford’s Oriel College, White returned to his home village of Selborne in 1755, where he inherited a house from Uncle Charles. (Today, The Wakes is a museum dedicated to White and another great Briton, Capt Lawrence Oates, of polar legend.)

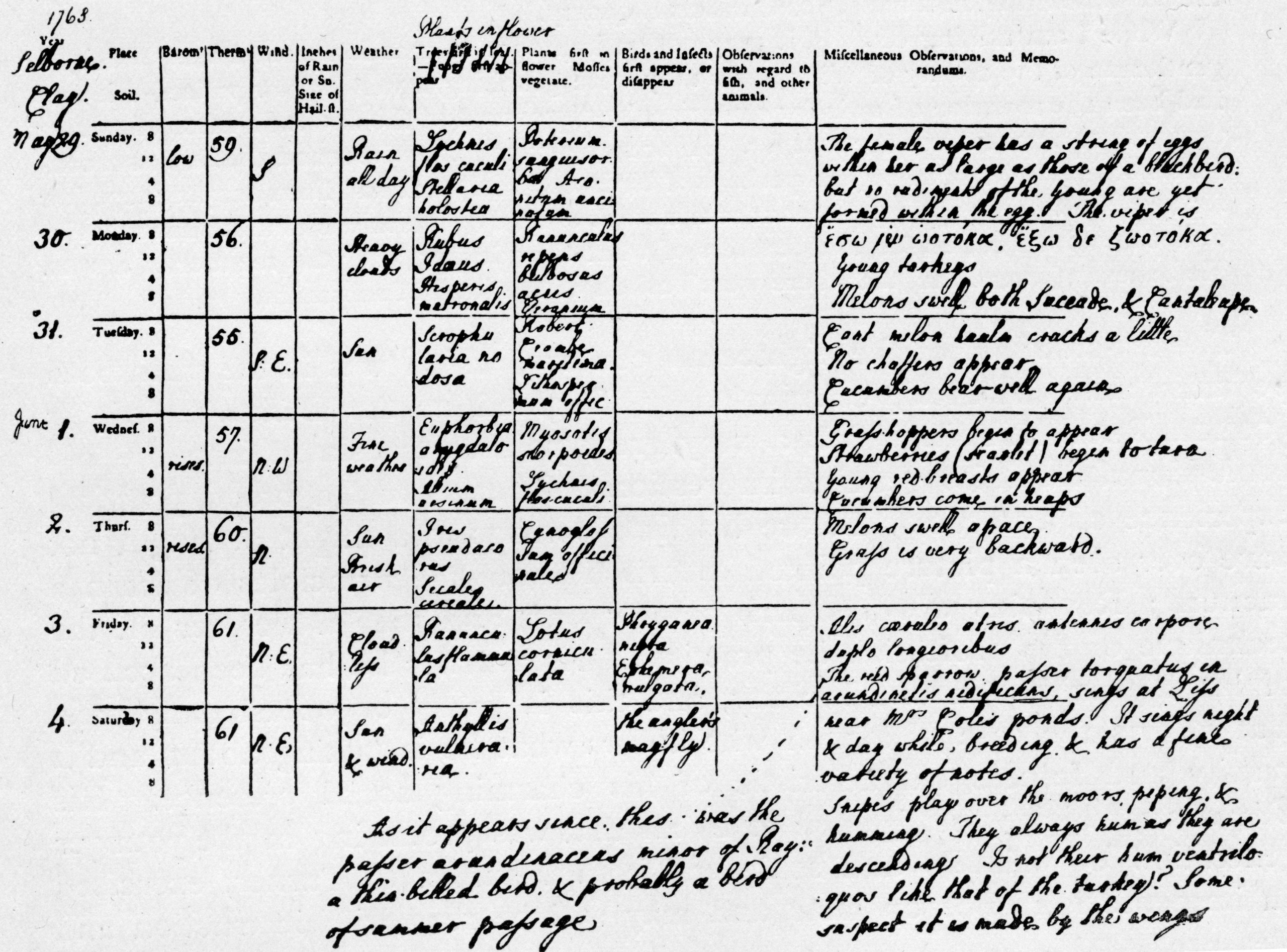

Truly, White’s regnum of this patch of tucked-away, hilly Hampshire should have been unremarkable, all buns and baptisms. Instead, he set about the close study of every natural aspect of the place, from the stone underfoot to the swallows of the air (he was much obsessed with the then mystery of avian migration), from the ‘long hanging wood called the Hanger’ to the rivulet at the end of the village. Each day, until the week before his death in 1793, he recorded the infinitesimal changes of Selborne’s flora and fauna. Parochial has become pejorative when it needs celebration; it was from local study that White expanded knowledge of the natural world, just as ink spreads on blotting paper.

In about 1767, he started up correspondence with two prominent naturalists, Thomas Pennant and Daines Barrington. His epistles to these men form the basis of The Natural History, a compilation published in 1789, the year of the French Revolution.

The gap between the timeless tranquillity of English countryside and the blood-running theatrics of France was absolute. Citizen Marat exclaimed the power of the plebs and the curate of Selborne exalted the earthworm: ‘Earthworms, though in appearance a small and despicable link in the chain of nature, yet, if lost, would make a lamentable chasm.’

Outside events rarely, if ever, impede on White’s Natural History. It is the book of England’s Eden and, apparently, the fourth most-published book in the English language, after the Bible, Bunyan and Shakespeare. Assuredly, it has been in print since first publication and the 300-odd editions have been illustrated by the likes of John Nash and John Piper.

Artists are drawn to it. Writing to a friend in 1936, Eric Ravilious said: ‘I read [Selborne] every minute I can spare from engraving and other jobs.’ Ravilious’s illustrations for the 1938 expanded edition, The Writing of Gilbert White of Selborne, are dreamily definitive, the absolute apex of art and Whitean words.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

More obviously, biologists have been beguiled by the book. The young Charles Darwin grew up with White’s Natural History at his bedside — even made a pilgrimage to the place, even based The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Actions of Worms (1881) on White’s wormy work. Churlishly, he didn’t give White his due; as paleobiologist Gerhard C. Cadée once remarked, ‘Darwin did not want to have a forerunner’ for his ‘original’ ideas.

To this day, White’s fieldwork is unparalleled. It was, literally, the parish-pump for a new species of biology — specific, scientific and based on the slow, certain accretion of detail. Such was the benefit of being a country cleric, fortuitously removed from the pandemonium of revolution, industrial and political.

The parson had the time to stand and stare. Take this item from 1773, concerning barn owls:

About an hour before sunset (for then the mice begin to run) they sally forth in quest of prey, and hunt all round the hedges of meadows and small enclosures for them, which seem to be their only food. In this irregular country we can stand on an eminence and see them beat the fields over like a setting-dog, and often drop down in the grass or corn. I have minuted these birds with my watch for an hour together, and have found that they return to their nests, the one of them or the other, about once in five minutes…

White put in the praxis. In 1776, to peer-review the claim by French anatomist Herrisant that cuckoos were stopped from laying their own eggs by a ‘protuberance in the belly’, White cut open a cuckoo, ‘exposing the intestines to sight’. Next, he dissected a ‘fern-owl’ (nightjar), an unequivocal egg-emitter, to find it had the same anatomy as Cuculus canorus. Ipso facto, Herrisant’s conjecture ‘seems to fall to the ground’.

His endeavours coincided with a moment in Georgian England when scientific inquiry was suddenly fashionable. The Natural History replaced the hitherto-existing falsehoods of folklore with piercingly exact (but felicitously expressed) observations. For example, White’s letter about a peacock’s tail:

Happening to make a visit to my neighbour’s peacocks, I could not help observing that the trains of those magnificent birds appear by no means to be their tails; those long feathers growing not from their uropygium, but all up their backs… By a strong muscular vibration these birds can make the shafts of their long feathers clatter like the swords of a sword-dancer, they then trample very quickly with their feet, and run backwards towards the females.

White’s was a life of firsts. He was the first to identify the harvest mouse (Micromys minutus), just as he was the first to distinguish the chiffchaff, willow warbler and wood warbler as three separate species. He discovered the noctule bat. He was the first to do a seasonal census of birds and instigated modern theories on bird migration. Biologists still read him for insight and information today.

Nothing in the natural world was alien to White. He slit open a viper to reveal the live young; he wrote a magisterial mini-treatise on echoes, complete with advice on constructing garden follies for best sound quality.

Our ideas about life on planet Earth were changed by the Victorian men of science, the Darwins and the Huxleys, the Russells and the Hookers — but they stood on White’s bones. If those contributions to the school of natural history are significant, his observation of events in Selborne over 40 years led him to develop the notion of a ‘food chain’, the interdependence of all things, thus commencing the modern study of ecology.

Scientists can be sniffy about White, suspecting that his religion rendered him un-objective (he has even been left off lists of ‘great British naturalists’). Actually, it was his religion that caused such intense personal wonder at the world.

In revering God’s work, the Reverend rejected, happily, the prevailing Descartian Enlightenment orthodoxy that fauna were mere flesh-robots, but proposed instead that they had inner lives. The members of the ‘winged nation’ are capable of a sort of talk, he told Barrington: ‘The language of birds is very ancient, and, like other ancient modes of speech, very elliptical; little is said, but much is meant and understood.’ In this respect for the creatures of the earth, the sea and the sky, he stands very close to us today.

Of course, none of the above wholly explains why The Natural History has proved so damnably readable across the churn and change of the centuries. Well, because it is English Literature, capital L, to rank alongside Austen, the King James Bible, Chaucer and Orwell. Literariness in Nature writing is a dangerous thing, too often rotting purple, the stuff so deliciously burlesqued by Evelyn Waugh in Scoop. ‘Feather-footed through the plashy fen passes the questing vole,’ penned poor Boot. White, very much a practising naturalist, always keeps the quill in check. His are the words that are poetic, but precise. He is the lovable, learned friend by one’s side, his only wish to show you his parish’s splendours.

Open any page of The Natural History and, immediately, you are there in Selborne, with the Reverend pointing out the stone curlews with their legs reminiscent of ‘a gouty man’, wood warblers making a ‘sibilious shivering noise in the tops of tall woods’ or telling you that the marsh titmouse, from early in February, makes ‘two quaint notes, like the whetting of a saw’.

Of course, he bemoans the weather. Bastilles might tumble, but England’s dodgy weather endures. In summer 1776, the vicar of Selborne noted:

My grapes, that used to be forward and good, are at present backward beyond all precedent, and this is not the worst of the story: for the same ungenial weather, the same black cold solstice, has injured the more necessary fruits of the earth, and discoloured and blighted our wheat.

Even in England’s Eden, a little summer rain must fall.

‘Drawn to Nature: Gilbert White and the Artists’, a showcase of White’s enduring influence, is at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, West Sussex, until November 15 — see www.pallant.org.uk

Curious Questions: How did a stork with a spear through its neck solve the mystery of the migration of birds?

For thousands of years, most people were convinced that birds hibernated in the winter — until a staggeringly resilient stork proved

The terrible truth about the cuckoo, and the 'monstrous outrages' it perpetrates on its foster parents and siblings

The cuckoo is a bird whose behaviour is so horrendous — when judged by human standards, at any rate —

Country Life's guide to England's 10 breakthtaking national parks

One year on from Michael Gove's consultation on our nation's national parks, we round up the reasons to visit the

Four people who've made farming and conservation work in perfect harmony

Farmers are often blamed for damaging wildlife populations, but, here, four land managers whose passion for conservation is making a

Toby Keel is Country Life's Digital Director, and has been running the website and social media channels since 2016. A former sports journalist, he writes about property, cars, lifestyle, travel, nature.