2,000 years of the dock leaf

Generations have sworn by dock leaves to take the sting out of a brush with stinging nettles — but modern medicine disagrees. Ian Morton explains more as he delves into the history and lore of this plant.

Stung by nettles? Rub the rash with a dock leaf. Who doesn’t know that? And it appears it was always so. The Anglo-Saxon chronicles of the late 9th century recorded it. In 1386, in Troilus and Creseyde, Chaucer quoted an ancient charm to be recited as the leaf was applied: ‘Netle in, dokke out.’ Folk practice and herbal advice down the centuries confirmed the idea and it was surely no coincidence that nettle and dock so often grew in close proximity.

And yet, the efficacy of the dock leaf in countering the chemicals released by Urtica dioica — the nettle — is dismissed by modern pharmacology. Scientists claim that the juice released from the leaves of Rumex obtusifolius has ‘no pharmacologically relevant properties’— in other words, it does absolutely nothing. Yet researchers do concede that it can still help: apparently the rubbing action, together with a placebo effect that’s been entrenched for millennia, does relieve the sharp pain of a sting. So carry on regardless of the science, just as countless generations have done in the past, and countless more will continue to do so in the future.

Relief from nettle stings was only part of a wider medicinal bounty apparently offered by dock leaves. Their virtue was declared in Bald’s Leechbook, a 9th-century collection of ancient medical lore (a manuscript of it is held by the British Library), as a remedy for ‘water-elf sickness’, an ancient expression that covered skin eruptions including chicken pox, measles and ergot poisoning (‘leech’, a dismissive word supposedly based on the use of the slimy annelid for blood-letting, derives from laece, Anglo-Saxon for doctor).

Bald’s text declares: ‘I have wreathed round the wounds the best of healing wreaths, so the baneful sores may neither burn or burst, nor find their way further, nor turn foul and fallow, nor thump and throb, nor be wicked wounds, nor dig deeply down: but he himself may hold in a way to health.’

The familiar broad-leaved dock Rumex obtusifolius had a variety of folk names, some reflecting its practical application. Butter dock arose from the dairy-farming practice of wrapping butter blocks in the leaves to keep them cool on the way to market. Doctor leaf was an East Anglian tribute to its value as an instant wrap for a bleeding scratch. Elsewhere, it was bitter dock, kettle dock, bluntleaf and smair dock. Rural folk appreciated the cooling and soothing effect of fresh leaves placed in their shoes. When tobacco arrived on these shores, gentlemen lined their pouches with dock leaves to keep the contents moist.

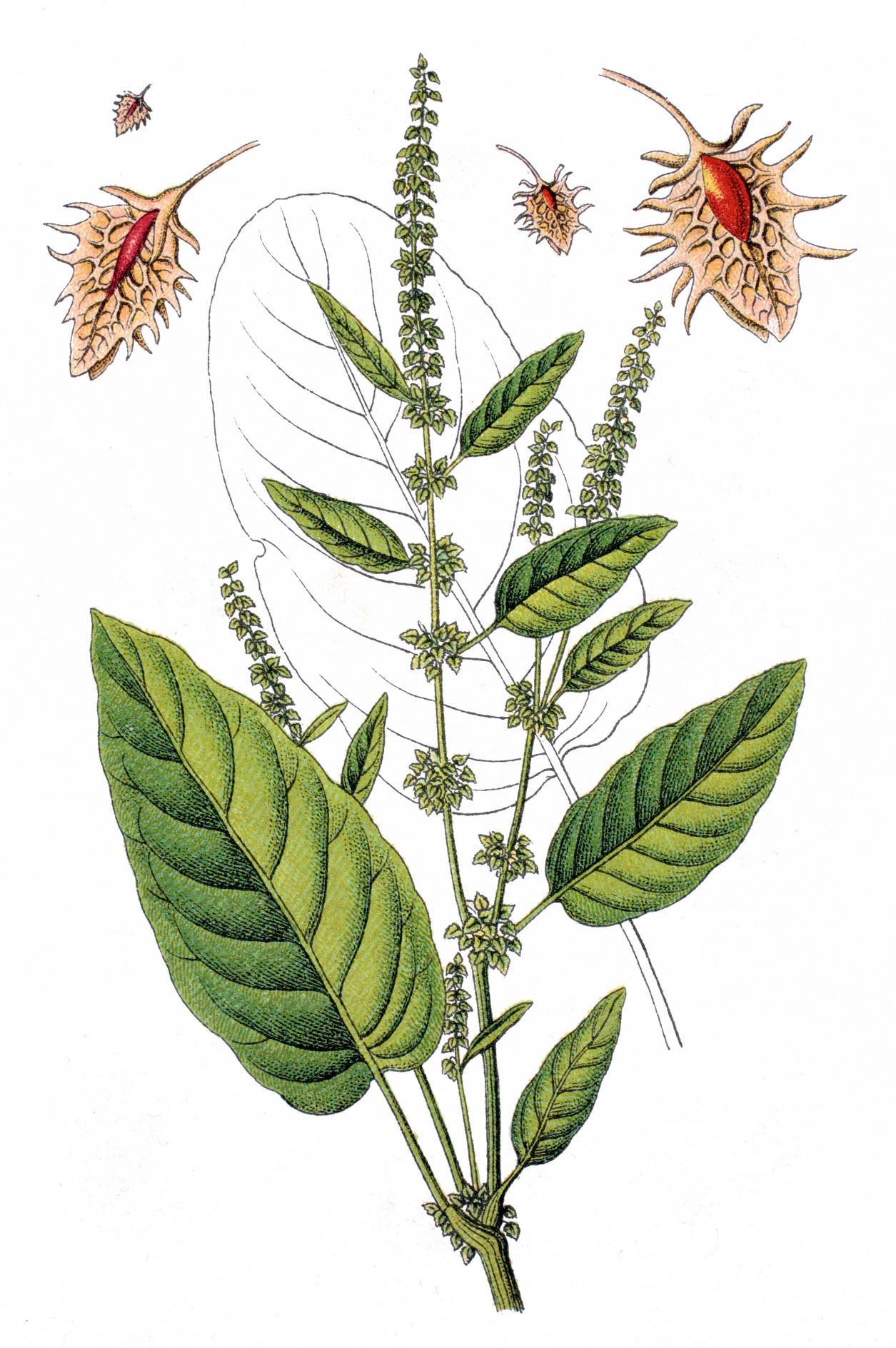

Equally valued was the curly-leaved Rumex crispus, also known as the yellow dock, sun dock or narrowleaf. Country children called it curly-cow or cushy-cow, squeezing the leaf stems to extract sap. Its crushed taproot was widely prescribed as a healing poultice for bumps, cuts and bruises, to be administered either plain, mixed with butter or boiled in vinegar and combined with lard. Culpeper declared in his Complete Herbal of 1653 that ‘the yellow dock root is best to be taken when either the blood or liver is affected by choler’. It was further thought to be a treatment for depression and loss of mental capacity and, in remote rural areas where Gaelic beliefs still lurked, its mystic power was used to release a child from possession by an unkind spirit.

Culpeper, an alchemist as well as a herbalist, who acknowledged the planetary influence that assigned docks to Jupiter, also valued the red dock Rumex sanguinea, found in shallow water: ‘Commonly called bloodwort (it) cleanseth the blood.’ He was a fan of all docks, which ‘have a kind of cooling (but not all alike) drying quality’, and recommended the consumption of their seeds, which he said ‘stay lasks (dysentery) and fluxes of all sorts’ and were ‘helpful for those that spit blood’. Culpeper was, in fact, harking back to ancient Greece, where Hippocrates recommended dock seeds to aid digestion and Dioscorides prescribed them for dysentery.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Together with sorrel relatives in the buckwheat family Polygonaceae, docks number some 200 species with worldwide distribution. The tallest variety, growing up to 6ft in height on river banks and less widespread and familiar than its field and wayside relatives, is the great water dock Rumex hydrolapathum. Its root was used in ancient times to treat loose teeth and soft gums. Pliny the Elder named it Herba Britannica, but not because it was British — the word was compiled from the Teutonic brit (tighten), tan (tooth) and ica (loosen).

When Julius Caesar’s troops were in the Rhineland, they suffered from diseased mouths and weakened limbs and were alerted by the local Frisii tribe to treatment with its root extract. Although scholars question whether the disease was indeed scurvy, this supposition passed into medical lore.

Considering ‘that plague and hurtful disease of the teeth, gums and sinuses called Scurvie… a disease happening at sea among Fishermen’, John Gerard surmised in his 1597 Herball that other plants might have been involved. Yet the dock survived such doubts and Royal Navy physician James Lind noted in his Treatise on the Scurvy of 1772 that ‘an infusion of this herb… has for some years past been sold in London as a great specific for the scurvy’. Notorious quack Dr John Hill prospered by purveying it, raiding the Chelsea Physic Garden for plants until he was banned, whereupon he grew them in his own garden in what is now Lancaster Gate.

All such enduring traditions considered, it seems a palpably brutal and single-minded bureaucracy that lumped our two common docks, the broad-leaved and the curly-leaved, together with ragwort, the creeping thistle and the spear thistle, under the provisions of the 1959 Weeds Act, requiring landowners to prevent their spread under threat of a £1,000 fine — but it was understandable.

The dock proliferates with undue generosity. The unprepossessing flower spike of a single plant can produce up to 60,000 seeds and a typical acre of arable land has been estimated to contain five million seeds, which can lie dormant for up to 50 years as their chemical constituents include one that inhibits microbial decay — an instance of self-medication, it would seem.

Both broad-leaved and curly-leaved docks flourish everywhere except areas prone to flooding. They like field margins, neglected corners, well-trodden and disturbed patches of ground and over-grazed land. Cattle farmers were never unhappy with docks because they help to avoid bloat (did they but know that its tannin helps precipitate soluble proteins). Sheep, goats and deer may graze it, but not horses.

The leaves also contain phosphate, magnesium and potassium, and deposits in cattle slurry spread on pasture in turn encourage new dock growth. Kitchenwise, the young leaves may be used raw in salads and cooked in vegetable broth and stews, making a fair substitute for spinach, although amounts should be regulated as the oxalic acids will promote kidney stones.

Swollen tongues and black mouths: Competitors tuck in at World Nettle Eating Championship

The Bottle Inn in Dorset is the host venue for the annual World Nettle Eating Championship, which invites entrants to

Curious Questions: How, and why, do people eat stinging nettles?

Every summer, people from around the world gather at a pub in Devon for the World Nettle Eating Championship. But

Credit: Alamy

Vegetables, cows and horses star in very countryside-friendly list of the best jokes at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival

The winners of the comic competition have been announced, while gags about Churchill, Brexit and Harry Potter have also received

After some decades in hard news and motoring from a Wensleydale weekly to Fleet Street and sundry magazines and a bit of BBC, Ian Morton directed his full attention to the countryside where his origin and main interests always lay, including a Suffolk hobby farm. A lifelong game shot, wildfowler and stalker, he has contributed to Shooting Times, The Field and especially to Country Life, writing about a range of subjects.