Curious Questions: What should you do if bats take up residence in your roof?

Watching bats flit across the night sky might be captivating, but their presence can be a challenge for the homeowners in whose roofs they roost. Jane Wheatley reports on what to do if a colony has taken up residence.

When Lauren Smart drove from London to view a dilapidated 18th-century farmhouse for sale near Charlbury, in the Oxfordshire Cotswolds, it was love at first sight. ‘I knew it would be a money pit, but I had to have it,’ she admits. What she didn’t know was that a roost of brown long-eared bats was already ensconced in the roof and pipistrelles had requisitioned a gable end.

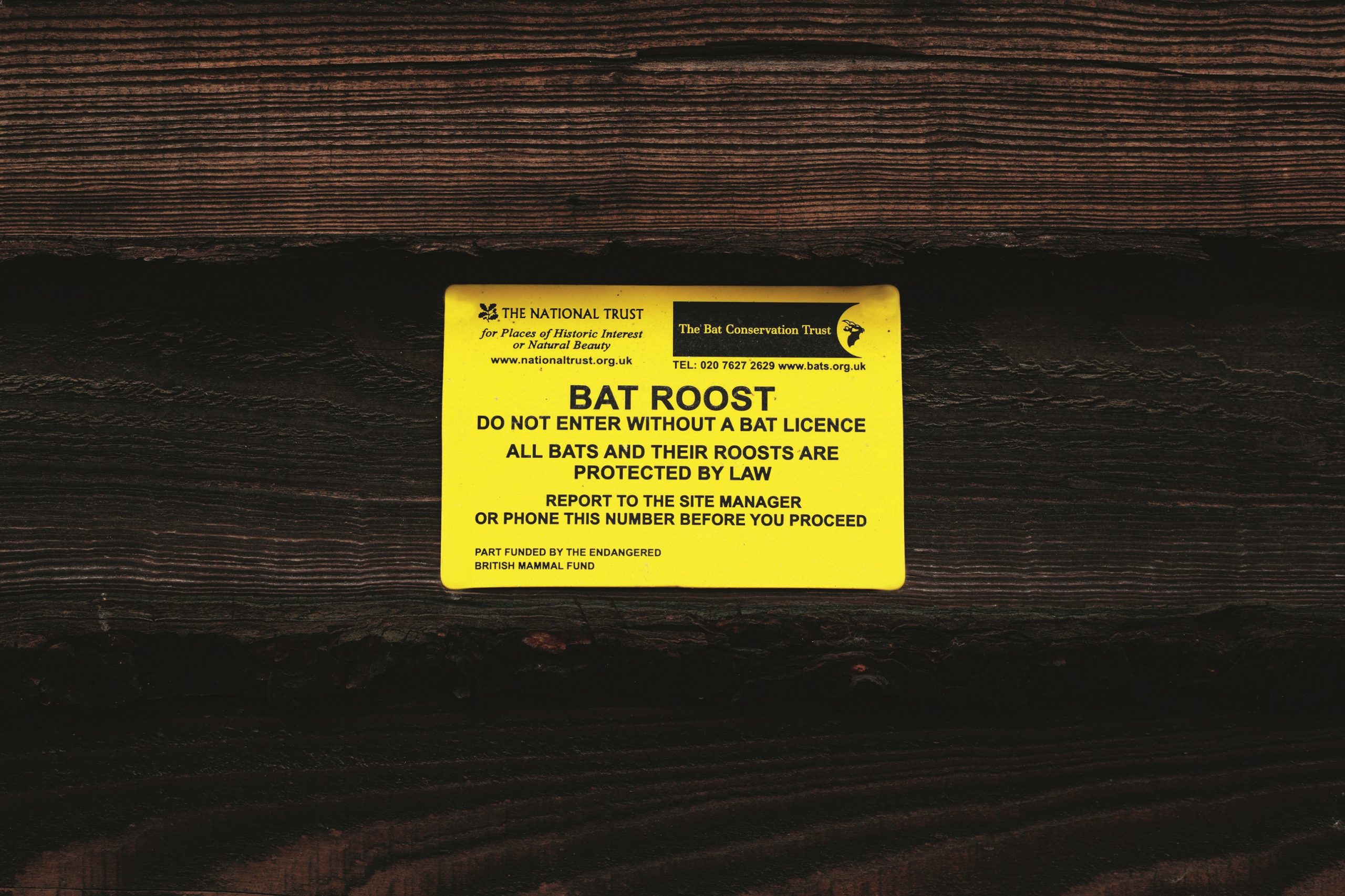

Before the Smarts could submit plans to renovate the house and convert the barn next door, a compulsory survey revealed that both roosts contained female bats with babies. All bats are protected by law, but maternity colonies have a high conservation value, returning to the same roost each summer to have their young: ‘We were told that we couldn’t touch the roof or the loft space until we’d provided alternative accommodation for them,’ Mrs Smart explains.

The first task was to convert the barn during the winter when bats move out to hibernation roosts elsewhere. ‘That was the easy bit,’ smiles Mrs Smart. ‘The pipistrelles came back, popping into the crevices we’d provided in the new brickwork and roosting under the bargeboards. We see them every evening swooping in and out; the surveyors counted 59 originally, but I think there are more now.’

The long-eared bats posed a bigger challenge, requiring a large vaulted space to mimic their roost in the house with enough room to fly around. The solution is a new two-storey building, housing garage and gym with bedrooms and a roomy attic on the upper floor — and specially designed access points along the tiled roof. ‘The bat house,’ announces Mrs Smart, opening a door into the warm, dark, windowless space.

The building work, including renovating the interior of the house and linking it to the converted barn, has been completed in several phases, each one prompting a further ecological survey to satisfy the requirements of a full bat licence from Natural England. Only the leaking, patched roof remains to be done this winter, once the bats have left with their babies.

‘So far, the surveys and licence applications have cost about £12,000,’ reveals Mrs Smart, ‘but the indirect costs of the bats have been huge.’ Yet, she seems remarkably sanguine. ‘Well, I work in sustainable finance, so I’m sympathetic to bats. My husband was incredulous at first; he said: “Can’t we just not tell anyone or smoke them out?”’

Bats have been a protected species in the UK since 1981 under the Countryside Act and from 1994 by EU legislation. Planning permission for building or demolition work, which could damage or destroy a roost, is likely to require at least an initial ecological report to establish whether bats are present. However, their absence is no guarantee of plain sailing.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Bernard Eacock is a planning consultant working on the borders of Herefordshire and Wales and advises clients to budget for potential survey costs. ‘In one case, the owners wanted to add accommodation to their existing house, which was obviously entirely unfit for bats; it had a fibrous membrane covering the underside of the roof — bats don’t like that, they get their claws stuck in it — and there was a blanket of cobwebs, which they don’t like either. However, the ecologist doing the initial visit thought he saw a bat emerge from one end. That meant three further surveys over three months at a cost of £3,000 to conclude there were no bats living there.’

At sunset on a calm, late-summer evening, I am standing with Grace Dooley from ecology consultancy Just Mammals on a cobbled yard outside an old brick stable block and coach house. Four colleagues are positioned at strategic points around the building, each with ultrasound detectors. Droppings have already indicated the presence of brown long-eared bats and a lesser horseshoe has been spotted snoozing under a rafter in one of the lofts; now, it’s almost feeding time and we wait.

Nothing happens for what seems like ages, then there is a fast chittering sound from the recorder and something tiny flashes over our heads. Then more chittering, then a little hoot, which I’m told is a social call, ‘making contact with other bats’. Another sound is a buzz, getting faster as a bat hones in on its prey. It’s all rather thrilling and, after an hour or so, everyone’s notebooks have recorded a satisfying amount of activity, including 17 bats counted emerging from the east side of the stable block. What will this mean for the owner’s plans? ‘I will probably recommend keeping one section of loft for the bats,’ says Mrs Dooley. ‘That will still leave plenty of scope for the development; we always aim for co-existence between human and bat.’

Ted Bodsworth heads Windrush Ecology in Witney, Oxfordshire, and boasts that he has never failed to get a bat licence for a client, but the process can be costly. ‘A typical scenario for a loft conversion would be an initial visit and report; three activity surveys, dawn and dusk, with three surveyors and an updated report to the local authority. Then the application for a full bat licence and I come out to supervise the removal of the roof for a day as a condition of the licence. Probable cost between £6,000 and £7,000.’

He tells me about a client who wants to demolish a house prone to flooding and rebuild on higher ground. ‘There was a maternity colony of 333 pipistrelles; alternative accommodation has to be provided before demolition, so a carport will be built in the winter as close as possible and in the same orientation.’

Does that mean that when the bats come back and find their old roost gone, they will say ‘oh look, here’s a nice new home’? ‘Between you and me, that’s probably not going to happen and now you’ll quote me,’ says Mr Bodsworth. I tell him I’ve heard grumbles from owners who have built expensive, so-called bat hotels that have never seen a single bat. He nods: ‘You have to provide suitable mitigation in the expectation that they will use it. If you can assure Natural England that it will be built in time, fit for purpose in the correct orientation and that everything is the best we can do, that’s when you get your licence. The bats may not come back, but I console myself: they are intelligent, they have a wide range; they will find another place.’

Jeremy Bugler always knew there were bats on his farm in Herefordshire’s Wye Valley; they roost in his attic, he sees them flitting about on his evening dog walk and the upper floors of an old timber barn are liberally coated in bat poo. However, it wasn’t until the Herefordshire Bat Research Group came to survey the place with nets, harp traps, infrared cameras and detectors that he learned he was host to 11 species, including noctules, natterer’s and a visiting barbastelle. ‘I had no idea there was such richness,’ he notes.

On a sunny summer afternoon, we walk down through water meadows thigh deep in wildflowers to the mere, one of a series of former ice ponds surrounded by alder and willow. ‘We farm fairly negligently, so it is a perfect habitat with plenty of food on the wing,’ points out Mr Bugler. ‘I often see whiskered bats skimming the water.’

Back at the farm buildings, we climb a flight of stone tallet steps to find a maternity colony of lesser horseshoes snuggled under the rafters of the barn and, next door, a substantial long-eared roost. Mr and Mrs Bugler once considered converting the barn for residential use: ‘But we never got around to it. I told the surveyors, we do absolutely nothing here, they said: “Please carry on”,’ he adds with a smile. ‘It was a nice endorsement of indolence.’

What is a garden hermit?

Martin Fone takes a look at the curious history of the hermits who spent years living happily in the grounds

10 ways to insulate a period property

Modern technology might offer sustainable, cost-effective heat sources, but the best-value unit of energy is the one you don’t lose

Credit: Getty Images

How to stop a dog destroying your lawn

Ben Randall fields a question about how to stop a pooch with a penchant for digging holes in its owner's

-

Curious Questions: Will the real Welsh daffodil please stand up

Curious Questions: Will the real Welsh daffodil please stand upFor generations, patriotic Welshmen and women have pinned a daffodil to their lapels to celebrate St David’s Day, says David Jones, but most are unaware that there is a separate species unique to the country.

By Country Life

-

Nobody has ever been able to figure out just how long Britain's coastline is. Here's why.

Nobody has ever been able to figure out just how long Britain's coastline is. Here's why.Welcome to the Coastline Paradox, where trying to find an accurate answer is more of a hindrance than a help.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious questions: how an underground pond from the last Ice Age almost stopped the Blackwall Tunnel from being built

Curious questions: how an underground pond from the last Ice Age almost stopped the Blackwall Tunnel from being builtYou might think a pond is just a pond. You would be incorrect. Martin Fone tells us the fascinating story of pingo and dew ponds.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: What's in a (scientific) name? From Parastratiosphecomyia stratiosphecomyioides to Myxococcus llanfair pwll gwyn gyll go gery chwyrn drobwll llan tysilio gogo goch ensis, and everything in between

Curious Questions: What's in a (scientific) name? From Parastratiosphecomyia stratiosphecomyioides to Myxococcus llanfair pwll gwyn gyll go gery chwyrn drobwll llan tysilio gogo goch ensis, and everything in betweenScientific names are baffling to the layman, but carry all sorts of meanings to those who coin each new term. Martin Fone explains.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: How did a scrotum joke confuse paleontologists for generations?

Curious Questions: How did a scrotum joke confuse paleontologists for generations?One of the earliest depictions of a fossil prompted a joke — or perhaps a misunderstanding — which coloured the view of dinosaur fossils for years. Martin Fone tells the tale of 'scrotum humanum'.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Why do so many animals have bright white bottoms?

Curious Questions: Why do so many animals have bright white bottoms?Why do so many animals have such obviously flashy appendages, asks Laura Parker, as she examines scuts, rumps and rears.

By Laura Parker

-

The 1930s eco-warrior who inspired David Attenborough and The Queen, only to be unmasked as a hoaxer and 'pretendian' — but his message still rings true

The 1930s eco-warrior who inspired David Attenborough and The Queen, only to be unmasked as a hoaxer and 'pretendian' — but his message still rings trueMartin Fone tells the astonishing story of Grey Owl, who became a household name in the 1930s with his pioneering calls to action to save the environment — using a false identity to do so.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Why do all of Britain's dolphins and whales belong to the King?

Curious Questions: Why do all of Britain's dolphins and whales belong to the King?More species of whale, dolphin and porpoise can be spotted in the UK than anywhere else in northern Europe and all of them, technically, belong to the Monarch. Ben Lerwill takes a look at one of our more obscure laws and why the animals have such an important role to play in the fight against climate change.

By Ben Lerwill