Curious Questions: How did a scrotum joke confuse paleontologists for generations?

One of the earliest depictions of a fossil prompted a joke — or perhaps a misunderstanding — which coloured the view of dinosaur fossils for years. Martin Fone tells the tale of 'scrotum humanum'.

Children seem to be gripped by dino-mania, entranced by the thought of some of the largest ever land animals tramping over our prehistoric planet. Based on online searches in 2020 Statista revealed that dinosaur toys were second only in the UK to ‘fidget toys’ and comfortably ahead of the rest of the field.

Paleontologists have long been adept at bringing their finds to life. Richard Owen commissioned Waterhouse Hawkins to create life-sized models of dinosaurs for the 1851 Great Exhibition, which later found a home in Crystal Palace Park. The first articulated skeleton of a dinosaur, a Hadrosaurus found in a New Jersey claypit in 1858, was given the Hawkins treatment, the mounting so arresting that the Academy of Natural Sciences had to starting charging for admission to limit the numbers of visitors. Casts were taken and sold to other museums around the world.

Illustrators took up the challenge of putting some flesh on the bones of dinosaurs, one of the earliest illustrations appearing in Camille Flammarion’s book, Le Monde avant la Création de l’Homme (1886). A striking image of an Iguanadon resting its front claws on the fifth storey balcony of a Parisian apartment block, the use of a backdrop of tall buildings to emphasise the creature’s size was soon to become an illustrator’s trope. American newspapers such as American Century in 1897 and New York World and Advertiser (1898), for example, ran illustrations of the far larger Brontosaurus against a background of skyscrapers.

Toy manufacturers soon seized on the fanciful reconstructions of the paleoartists to create thin, scaly figurines. While they were far removed from what scientists now think the creatures were like, they were sufficient to fire a child’s imagination, although they were not wildly popular. There was little commercial incentive for manufacturers to update their moulds to reflect the advances in scientific understanding of dinosaurs during the twentieth century, that is until the film Jurassic Park was released in 1993. The phenomenal success of the film, grossing over $1 billion, prompted toy manufacturers to release a new wave of improved dinosaur toys, making them the must-have toys for children.

Finding fossilised bones was not a modern phenomenon. Myths about dragons, leviathans and other strange creatures probably were developed to give an explanation for the remains of extinct terrestrial and maritime creatures that cropped up from time to time. In ancient Greece King Pelops’ lost ‘shoulder blade’ and the skeleton of Orestes, described by Herodotus as being over ten feet tall, were probably fossilized remains of mammals such as mammoths or mastadons from the Pleistocene era.

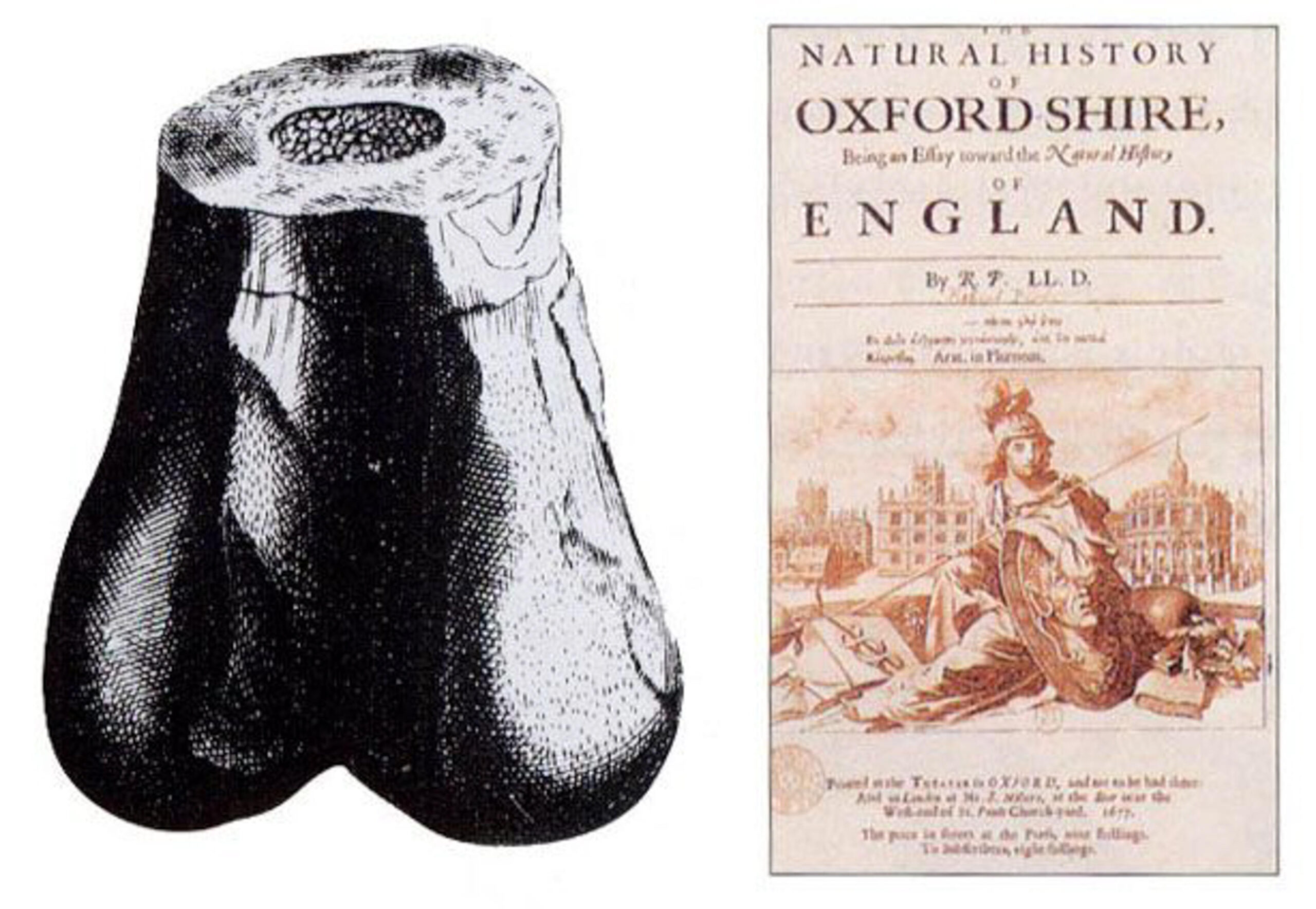

The first ‘scientific’ description of a fossil appeared in Robert Plot’s Natural History of Oxfordshire (1677). Plot identified what had been unearthed in the Taynton Limestone formation in Cornwall as part of a femur, larger than that of a horse or ox. To help his readers visualise the find, he included an illustration — one which would, in future years, play a bizarre role in the history of scientific classification.

Rejecting suggestions that it was a natural formation of crystallised mineral salts or the remains of an elephant brought over during the Roman occupation, Plot suggested that the femur belonged to a giant human being, similar to the Titans of Greek mythology. He devoted several pages of his book to a summary of their history and sought to strengthen his case by drawing comparisons with several contemporary tall humans, including a Dutch woman ‘seven feet and a half high, with her limbs proportionable’, whom he had seen in Oxford.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Almost a century later, naturalist Richard Brookes applied the newly developed Linnaean taxonomical system to British stones, fossils, and minerals in his A New and Accurate System of Natural History (1763). Included in the fifth volume was a description of Plot’s fossilised femur, adding little to the original account. There was an accompanying illustration, again remarkably similar to that in Plot’s account a century earlier save for two points: it was inverted and bore the rubric Scrotum humanum.

Brookes clearly believed, like Plot, that the fossil ‘exactly resemble[s] the lowermost part of the thigh-bone of a man’, but crucially just before his description of the fossil he had remarked how ‘other stones have been found exactly representing the private parts of a man’. The illustrations accompanying the text were only identified by the page number of their description and it is possible that the illustrator, in inverting the fossil so that it looked like a male private part, labelled it accordingly.

On the other hand, it might just have been a joke.

Either way, it was to cause enormous difficulties for future paleontologists.

The French philosopher and naturalist, Jean-Baptiste Robinet, included a description and illustration of the fossil in his Considerations philosophiques de la gradiation naturelle des forms (1768). Although much was drawn from Brookes’ description, Robinet went further, claiming to be able to identify the musculature in each ‘testicle pouch’ and remarking that the central cavity resembled a urethra. Rejecting the idea that the fossil was the petrified bone of a once-living creature, he thought it was a geological phenomenon created by ‘mineral germs’, a theory that was not widely accepted.

William Buckland described ‘an enormous fossil… reptile’ in Notice on the Megalosaurus or great Fossil Lizard of Stonesfield (1824), which had been unearthed in the slate near the Oxfordshire village. He assumed it to be ‘an amphibious animal’, unsurprisingly as Mary Anning’s Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus and Georges Cuvier’s giant monitor lizard, found in Maastricht, were clearly water-dwelling. Today we know that Buckland’s Megalosaurus or ‘great lizard’, was a six-meter long land-dwelling carnivore. Crucially, Brookes’ Scrotum humanum was probably a femur from a similar Megalosaurus.

"Scrotum humanum had priority over Megalosaurus bucklandii and future generations of paleontologists were stuck with this uncomfortable fact"

In 1827 Gideon Mantell, applying Linnaean rigour to Buckland’s fossil, gave it the type species of Megalosaurus bucklandii, while Richard Owen, in 1842, used the name Megalosaurus to describe one of the genera that defined the group Dinosauria. By this time, it was beginning to dawn on the perceptive scientist that dinosaurs were distinct animals in their own right rather than just types of large lizard.

This raised a significant taxonomical dilemma, though. Under the Linnaean system the first name given to a specimen has taxonomic priority over later names. Inescapably, not only was Scrotum humanum a valid binomen but it was also the first generic and specific name to be applied to a non-avian dinosaur. In other words, Scrotum humanum had priority over Megalosaurus bucklandii and future generations of paleontologists were stuck with this uncomfortable fact.

The question of what to do about it rumbled on well into the late twentieth century. A rather obscure rule in the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) came to the rescue. The last time that the term Scrotum humanum had been used in scientific literature was in 1899 and by 1970 paleontologists were able to apply to have it designated as a nomen oblatum or forgotten name so that its taxonomical priority could be overridden. The ICZN agreed in a decision described at the time as ‘perhaps fortunate’.

However, the very saviours muddied the waters again in 1985 when revising the code, the ICZN dropped the nomen oblatum rule. Paleontologist William Serjeant had to make a special application for Scrotum humanum to be suppressed once more so that it could not take priority over a name deemed to be more appropriate.

Curiously, the original fossil that caused all the fuss disappeared without trace, possibly shortly after Plot had described it. Probably Brookes had never seen it but the consequences of his error, deliberate or accidental, rumbled on for a couple of centuries. Sub-editors, beware!

There's dinosaurs in them thar hills: How Britain discovered the Megalosaurus

There's not much to say about the Oxfordshire village of Stonesfield, apart from the fact that it was once 'covered

Good news for South London's most famous dinosaurs as the National Heritage Lottery Fund set to spend £30 million on its 30th anniversary

Castles, railway stations and Victorian dinosaurs are among the beneficiaries as the National Lottery Heritage Fund announces its latest plans.

There are 200 chalkstreams in the world, almost all are in England, and they're the most biodiverse freshwater habitat on the planet

Chalkstreams were forged millions of years ago when Europe was largely underwater and developed into unique and complex habitats that

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.