Blue tits: Beautiful birds, wonderful singers... and absolutely no morals

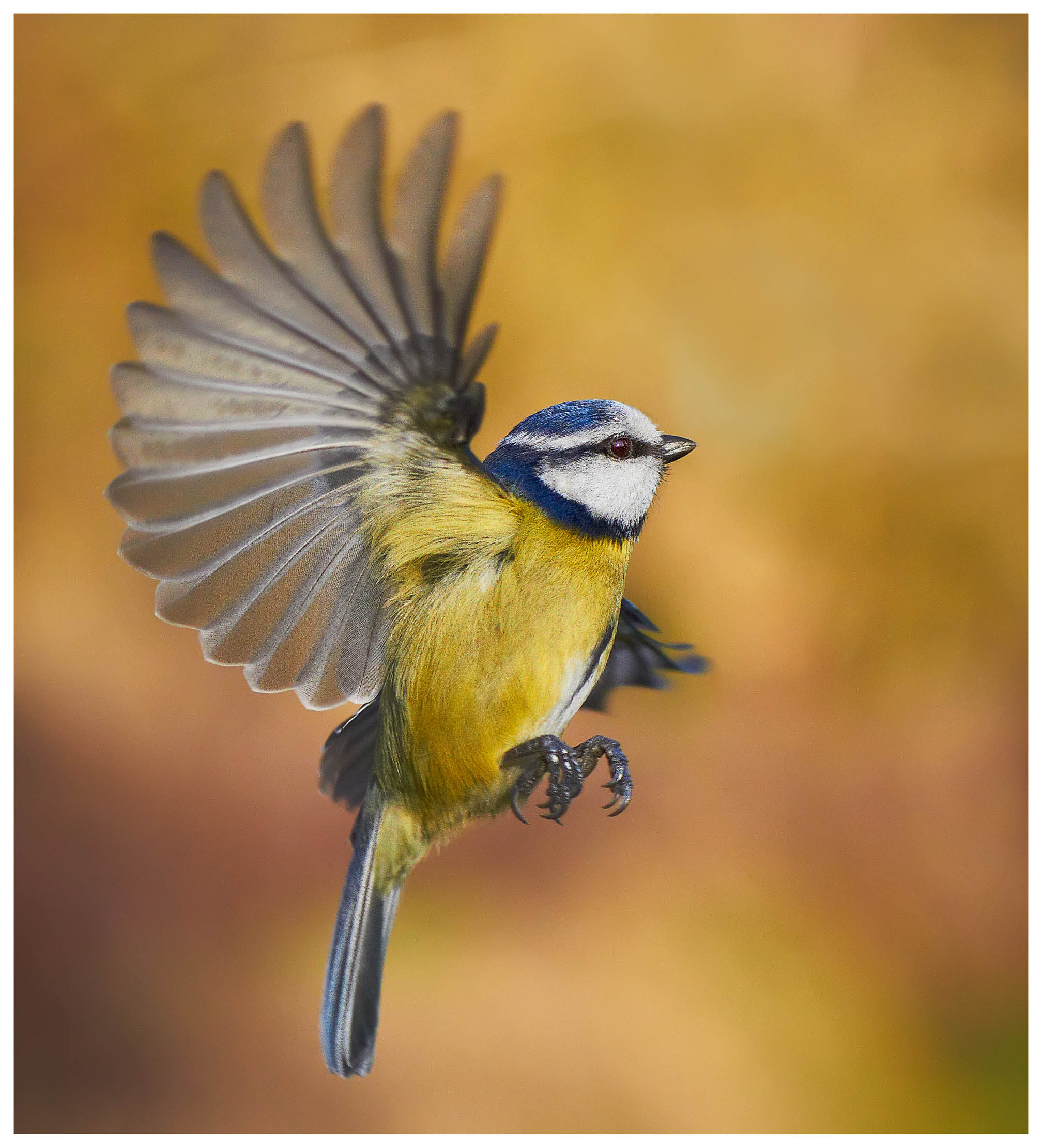

With a cobalt cap, white cheeks and tiny wings, the blue tit might be a picture of songbird sweetness, but its morals leave much to be desired, says Stephen Moss.

Whether you live in a town or in the heart of the countryside, chances are that blue tits stop by your bird feeders. Together with the robin, blackbird and wren, the species is a regular garden visitor, with the British Trust for Ornithology’s Garden Birdwatch recording it in roughly 85% of surveyed gardens, across all seasons. Small, perky and brightly coloured, it is also one of the easiest birds to identify, with its distinctive blue cap, white cheeks and yellow breast. Only 4½in long, it weighs less than half an ounce, between a £1 and a £2 coin.

As are many other resident birds, blue tits are very sedentary: they rarely travel more than 10km (a little more than six miles) from where they were born, although, occasionally, birds do flee hard winter weather on the Continent and turn up in eastern Britain.

What they lack in long-distance flying, however, they make up in energy: they are constantly active, because, being a small bird, they need to eat between one-quarter and one-third of their body weight every single day in order to survive, especially during the short and chilly days of winter. Outside the breeding season, they often travel in mixed flocks with other small songbirds, maximising their chances of finding food.

If they do survive the winter — typically, a blue tit will live for two or three years, although the oldest ringed bird went beyond its 10th birthday — they will start to pair up early in the spring, with the male courting the female by bringing her morsels of food. He will then defend his territory by singing his rather tuneless, slightly irritable song, which repels rival males, as well as cementing the bond with the female.

The pair will then seek out a place to breed: they evolved, as have many woodland species, to nest in holes and crevices in trees, but, together with so many of our garden birds, they take readily to artificial nest boxes, which can now be fitted with cameras to see what goes on inside.

Whether they have chosen a natural or an artificial site, the female alone builds the nest out of pieces of grass, loosely arranged to form a circular cup. She makes a small depression in the centre, which she then fills with soft moss, where she will lay between eight and 10 eggs — one of the largest clutches of all our garden birds. Once this is complete, the female starts to incubate the eggs and the chicks hatch between 13 and 15 days afterwards. They only have one brood.

Then the real hard work begins: both male and female spend every daylight hour hunting down oak moth caterpillars or other invertebrates and bringing them back to the nest to feed their hungry chicks.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

On average, they must find no fewer than 1,000 food items every day — and that’s not counting what they need to keep up their own energy. Outside the breeding season, they feed on a wider range of food, including seeds and nuts, often visiting bird tables and hanging feeders to snatch a free meal.

Since the BBC’s Springwatch was first broadcast in 2005, blue tits have always been among the stars of the series — a particularly memorable one was Runty, the smallest chick of the brood, which presenters Bill Oddie and Kate Humble finally witnessed leaving the safety of his nest box for the outside world, after much encouragement from his parents.

Or his supposed parents. The Latin saying that ‘the mother is always certain, the father isn’t’ holds especially true for blue tits: scientists have discovered the astonishing statistic that 40% of the species’ nests contain at least one chick — and often more — that’s not the offspring of the male bird rearing it.

Once thought to be monogamous, most male songbirds seek to maximise their chances of raising more young — thus passing on their genetic heritage — by mating with females other than the one with which they have paired up. Females, of course, cannot simply raise more chicks, but they can hedge their bets by mating with other males, so that their family includes more diversity than if they stayed faithful to their mate. They have devised clever strategies to avoid being spotted when being unfaithful, but, sometimes, males will notice the intruder and chase him away before the damage is done.

When it comes to picking a mate, one of the most extraordinary aspects of blue-tit biology comes into play — one that is impossible for us to see. When we look at a male or female blue tit, they appear identical to one another; yet the blue cap of the male is not only more intense than that of the female, but the females use this intensity — which they can see because, unlike us, they are able to detect ultraviolet light — to choose between potential mates.

Despite their beauty and widespread presence across British gardens, parks and woodlands, blue tits rarely feature in our literature, unlike robins, thrushes or wrens. There is, however, one notable exception: George Orwell’s poem Summer-like, which places this humble little bird centre stage:

A blue-tit darts with a flash of wings, to feed Where the coconut hangs on the pear tree over the well; He digs at the meat like a tiny pickaxe tapping With his needle-sharp beak as he clings to the swinging shell.Then he runs up the trunk, sure-footed and sleek like a mouse, And perches to sun himself; all his body and brain Exult in the sudden sunlight, gladly believing That the cold is over and summer is here again.

It’s a lovely tribute to one of our favourite garden birds — one with a fascinating, if slightly risqué, secret life.

Picture credits: Alamy, Getty, Shutterstock, Nature Picture Library

Why some birds mate for life – and why some play the field (and the trees, ponds and rooftops)

Cooing doves might be synonymous with lasting love, but, when it comes to romance, the bird world isn’t entirely faithful,

The Blue Tit: The cheerful harbinger of Spring

Victoria Marston takes a look at the cheerful, colourful bird whose busy activity is such a feature of the season.

Stephen Moss is a BAFTA-winning television producer, author, Guardian birdwatching columnist and naturalist living in Somerset, where he runs an MA in Nature and Travel Writing at Bath Spa University. His latest book, ‘Ten Birds that Changed the World’, is published by Faber. His website is www.stephenmoss.tv.

-

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old Masters

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old MastersThe younger generations’ appetite for everything vintage bodes well for the future, says Huon Mallalieu, at a time when an extraordinary Old Masters collection is about to go under the hammer.

By Huon Mallalieu

-

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comeback

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comebackThe Kentish glory moth has been absent from England and Wales for around 50 years.

By Jack Watkins