Beech trees: A complete guide

The beech tree is one of the finest sights in British woodland: effortlessly tall and graceful, offering year-round colour in a hardy, native variety. We take a look at what you need to know about the 'Queen of Trees'.

Is any tree lovelier than the beech? When the new season’s leaves begin to push out from long, pointy buds, we can be certain that spring is here. In no time at all, the emerging leaves will shake out their tightly packed pleats. Many opening buds are rosy-salmon coloured, but as the sap and chorophyll flow, expanding and ironing-out each leaf, the freshest of spring greens will appear in horizontal layers through the tree canopy, casting shadows on the woodland floor.

By summer, in field and parkland, statuesque trees that have survived a century and longer will give deep, welcome shade to sheep and cattle in the hottest days. Autumn sees Fagus sylvatica becoming even more glorious, with luminous hues of liquid gold and burnished copper before they fall.

In ‘mast years’, when the tree’s bristly seed capsules are plentiful, various rodents and birds will eat their fill — and store some more. Among them may be the lime-green, ring-necked parakeet. Ubiquitous in the south-east, these exotic creatures will descend on a well-fruited tree in large, squawking flocks. As a fast-food joint, beech then has few rivals.

Where are beech trees found?

When any child begins to learn how to identify British trees, the beech will be among the first: they are widely established and distinctive. They are generally considered native to south-east England and south-east Wales, becoming established roughly 2,000 years after the last ice age. It grew in particular in a band reaching across the country from the Wash, in East Anglia, to the River Severn.

Today, however, the Beech is naturalised — and indeed common — across the whole of Britain, having been planted widely for the benefit of their timber and nuts.

There is also some evidence that it may have been spread more widely across Scotland and northern England than previously thought, and might be considered native across the country.

Within that, beech tends to thrive on well-drained soil and struggle where the ground is damp; it's often found on chalky soils, limestone and light loam, and particularly in upland locations where some of the very oldest specimens are to be found.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

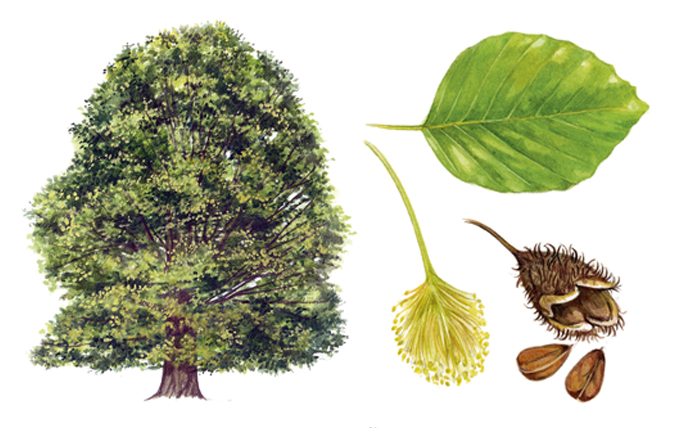

How to identify a beech tree

The mature beech — which can reach 130ft and develop a massive, many-branched dome — is a sight to behold, especially when it comes into bright-green leaf in May. No wonder the tree has earned the nickname ‘Queen of Trees’ (with the King being the oak tree).

They are among the biggest trees in Britain. One along the banks of the River Derwent in Hagg Wood, Derbyshire, was measured at 45m in 2018, and is believed to be the tallest native tree of any kind in the country. A different beech is also the nation's thickest tree: the Plas Newydd Beech on Anglesey, with a trunk girth of 10m.

With bark as smooth as stone, the beech’s trunks inspired the pillars of our great Gothic cathedrals; the tree’s heavy foliage makes for a sacred dark stillness outdoors. The dense canopy means only shade-tolerant plants can survive — in many of the beech woods across the Chilterns you’ll find a forest floor carpeted in bluebells, for example. Some orchids also tolerate the conditions well, as do funghi.

The beech tree leaves are particularly distinctive, with their oval shape, well-defined veins and wavy edges. When the leaves are younger they are bright green and silky; as they age they become darker and lose their softness.

Once the leaves change colour, the beech becomes one of the great sights of the countryside. Splendid stands of these trees set the countryside ablaze in autumn, as their foliage transforms to yellow, orange, then rich red-brown. At their best they are as striking as anything to be found in Japan or New England: ‘Personally, I’d prefer a mellow Buckinghamshire beech to New England’s fiery finest any bright autumn day,’ says Mark Griffiths in his piece on why leaves change colour in autumn.

Both male (tassel-like) catkins and female flowers grow (in pairs, encased by a cup) on the same tree, which, once pollinated by the wind, houses the beechnuts — or beech mast as they’re often known.

Be careful not to mistake a beech for a hornbeam, however: the two have similar leaves and shape and so are often mixed up. The buds on winter twigs of hornbeam lie flat, rather than sticking out at a wide angle as with beech. A fluted trunk also distinguishes the tree, along with hanging clusters of triangular, ribbed nutlets ringed by long, three-lobed bracts.

What is beech wood used for?

Beech timber has been valued since the Bronze Age and the close, straight grain of its wood, which is both hard and smooth, has long made it the go-to timber for furniture, tool handles and kitchen utensils. It's also widely used in sports equipment and musical instruments – particularly guitars. And while it's strong and hard it is still relatively easy to work with, and — thanks to the size the tree grows — can be cut in long lengths making it useful for flooring... though only with care since it's not moisture resistant.

It can also be used as firewood, since the logs are easily split and will burn well. Beech is the wood traditionally used to smoke kippers.

Can you eat nuts from a beech tree?

The short answer is ‘yes’. Indeed, the fruit of the beech tree — also known as beech mast or beechnuts — used to be eaten much more frequently than they are now, though that’s scarcely surprising as you’d be hard-pushed to find them in the average supermarket today.

The tree’s relatively rapid spread across the country is thought to be in part due to Neolithic Britons planting them for food; but it wasn’t just a northern Europe phenomenon. Over on the continent, the ancient Greeks were also known to eat beech mast.

Harvesting them at scale is essentially impossible, so they’re the preserve of foragers. They can be eaten raw, though as they contain a toxin called saponin glycoside it’s best to cook them first, unless you want the wind to blow through more than just the treetops.

Five minutes in a pan should do the trick; and you’ll be able to find a few recipes out there, from beechnut oil to beechnut butter. Historically, they have been pressed for oil and even ground as a coffee substitute — both are particularly popular in France.

How long do beech trees live for?

A beech can live a very long time indeed — certainly 400 years and older, particularly if they’re pollarded (i.e. pruned in order to limit its maximum growth). The Plas Newydd Beech on Anglesey is thought to be even older — and at 10m in girth, it’s the thickest-trunked tree in Britain.

How many types of beech tree are there?

By far the two most common types of beech are the European Beech — Fagus sylvatica, the one found across Britain — and the American Beech, Fagus grandifolia. A further dozen naturally-occurring varieties do exist in Asia, but gardeners have created dozens of variations of beech and the RHS now list over 150.

Of those — and aside from the main two varieties — you’re most likely to come across Copper Beech (Fagus sylvatica 'Purpurea'), Weeping Beech (Fagus sylvatica 'Pendula'), Japanese Beech (Fagus crenata), Chinese Beech (Fagus engleriana) and the exquisitely pretty Tricolor Beech (Fagus sylvatica 'Purpurea Tricolor’).

How do you grow a beech tree?

Look for a well-drained, sunny spot that's away from any frost pockets, which can damage the young leaves. Sunnier spots are best to get the strongest colours from purple-leaved varieties, while a little light shade will help golden varieties thrive.

You can either get a plant from a nursery — if so, planting between October and February is recommended. Alternatively, you can grow a beech from a seed: plant it as soon as you forage it in the Autumn.

Water the growing beech for the first couple of seasons, and keep its base free of other plants — a layer of bark chips or leafmould at the base will suppress weeds and help the young roots. They don't need feeding, but from the second season onwards general-purpose fertiliser can help them grow a little more quickly if that's what you're after, and also help the plant recover after pruning.

How do you grow a beech hedge?

Beech makes superb hedging, thanks in large part to one quirk of the plant: when it's trimmed and shaped, the leaves don't fall off in winter. This means that it can act as a natural visual barrier all year round.

They can be kept small (as little as 2ft/60cm) or grow many metres high. So much so, in fact, that the longest and tallest hedge in the world is a beech: the Meikleour Beech Hedge in Scotland is 530m long (a third of a mile) and 30m (100ft) high.

The beech used is the same plant — Fagus sylvatica — as the tree, though you can also make a hedge from Copper Beech. Source one from a hedging specialist and you'll get plants that are the right size and ready for planting at 45-60cm intervals (18-24 inches).

Pruning it back in August will set the shape and encourage the hedge to keep its brown leaves all winter; it'll need tidying again in Feburary.

Beyond the care you give to a normal tree, watch out for older branches growing out of control, and keep an eye on any sign of fungal infection.

How have beech trees inspired literature?

In the 1770s, James Stuart lined the approach to his house in Co Antrim with beech trees. These grew into the tunnel of writhing limbs now known as The Dark Hedges, a landmark so gothic in atmosphere that it has served as a location for Game of Thrones.

Beech trees inspired fantasy stories well before that, however. J. R. R. Tolkien drew on all manner of ancient folklore and mythology in his ‘Lord of the Rings’ trilogy and it is thought that a visit to the standing stones encircling the village of Avebury in Wiltshire inspired one of his most striking sets of characters. Near the eastern entrance of the earthworks at Avebury can be found four magnificent copper beech trees, their roots knotted and intertwined into a textured carpet on the ground.

This calls to mind Tolkien’s ‘Ents’, the walking, talking, tree-like creatures that act as guardians of the forest. Tolkien even goes on to describe how, in old age, Ents would lay down their roots permanently, becoming ‘treeish’ in their wizened state.

Additional writing: Mark Griffiths, Simon Lester, Toby Keel

A simple guide to identifying British trees

Simon Lester goes out on a limb to identify species and stop us barking up the wrong tree.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

The 10 most famous trees in Britain, and the (often grisly) stories behind them

Alan Titchmarsh: The joy of identifying trees in winter from the merest scrap of twig

Our columnist Alan Titchmarsh gives thanks for the tough training he received half a century ago – and how it

Looking after trees: Signs of stress, what to do, and when to call the experts

Kenton Smith and Tony Kirkham, author of the Haynes guide Trees, give their tips on making sure the trees in

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

The Ash: Is this the last stand for one of Britain's great native trees?

Mark Griffiths celebrates the historic, handsome and irrepressible native ash.