A simple guide to the seaweed of Britain

Naturalist John Wright explains what to look for when you come across seaweed on Britain's beaches this summer.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

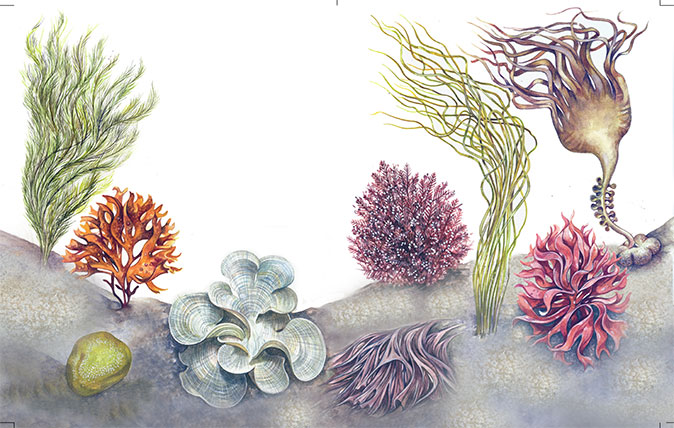

No gardener can match the perfection of beauty found in a rock pool. The many browns, greens and reds of the seaweeds are naturally arranged for greatest artistic effect and currents and small waves dramatically change the view every few seconds as the fronds slip over one another and the light changes. Flashes of iridescent blue from the tiny clustered bubbles of oxygen that collect on the seaweed fronds sometimes outshine those sombre colours.

But its beauty is just the start. Amid the flotsam and jetsam on our beaches lies a rich abundance of brown, green and red seaweeds which can be put to good culinary and cosmetic use. Here are 10 to look out for.

Rhodophyta

(Corallina officinalis)

Although a delight to even the casual eye, Corallina officinalis requires close attention for its more subtle beauty to be seen. The fronds are made up of hundreds of hard, pink, articulated tubes, like some tiny machine. Most organisms take some measure to ensure that they’re not eaten: we run away, but Corallina officinalis builds its fronds out of calcium carbonate and thus makes itself too difficult to eat.

‘Officinalis’, incidentally, is found in the Latin names of species used by apothecaries. In this case, the ground-up seaweed was used to remove intestinal worms – presumably employing the drastic method of scouring them out.

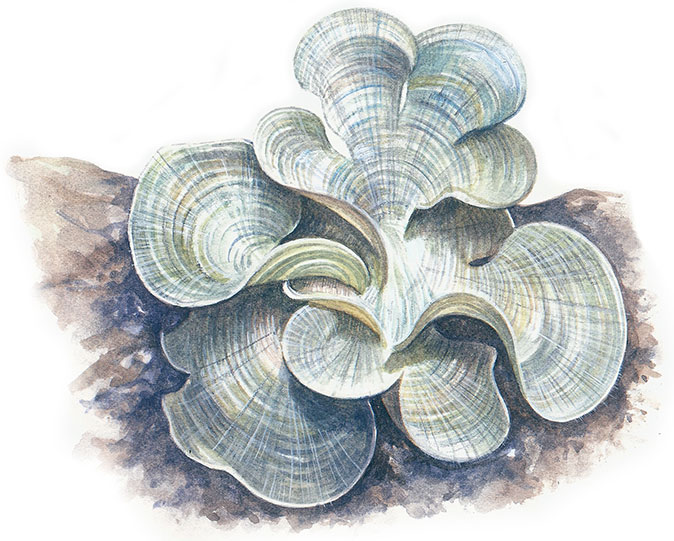

Peacock’s Tail Phaeophyta

(Padina pavonica)

Peacock’s tail is something of a south-coast specialty. It gets a mention because it’s one of the prettiest of the seaweeds, forming clusters of its fan-shape fronds in rock pools. This species is an example of a seaweed that’s found a use as a cosmetic – as an anti-ageing cream.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Carragheen Rhodophyta

(Chondrus crispus)

Seaweed pudding, anyone? Carragheen contains complex carbohydrates called carragheenans, which have a talent for setting a panna cotta. Boiled for half an hour, copious quantities of green slime are produced, which is then strained through muslin and whisked with sweetened warm milk and cream. It’s appropriately tasteless, but the slime puts people off a bit. As one schoolboy exclaimed during a demonstration of seaweed cookery I once gave at my daughter’s school: ‘Yuck, he’s making pudding out of snot.’

Gutweed Chlorophyta

(Ulva intestinalis)

A seaweed of the upper shore, gutweed is able to tolerate very low salinities. Both common and Latin names come from the fronds, which are, in fact, tiny tubes. These inflate with the oxygen of photosynthesis and float in rock pools like curled intestines. It’s a rather boorish seaweed, fast-growing under normal conditions; its growth becomes overwhelming when the sea is polluted with nitrogen and phosphorous compounds.

At Sandy Bay in south Devon, some years ago, I discovered that its mile of very wide sandy beach had disappeared completely beneath an 8in layer of this seaweed. The council had begun bulldozing it into several seaweed mountains, which produced no-go areas on the beach because of the impressive (and lethal) smell of hydrogen sulphide. Actually, there is another, nicer, smell associated with Ulva species – that of truffle. The chemical common to both is dimethyl sulphide. It is of critical importance for regulating climate by controlling cloud formation and most of it comes from seaweeds.

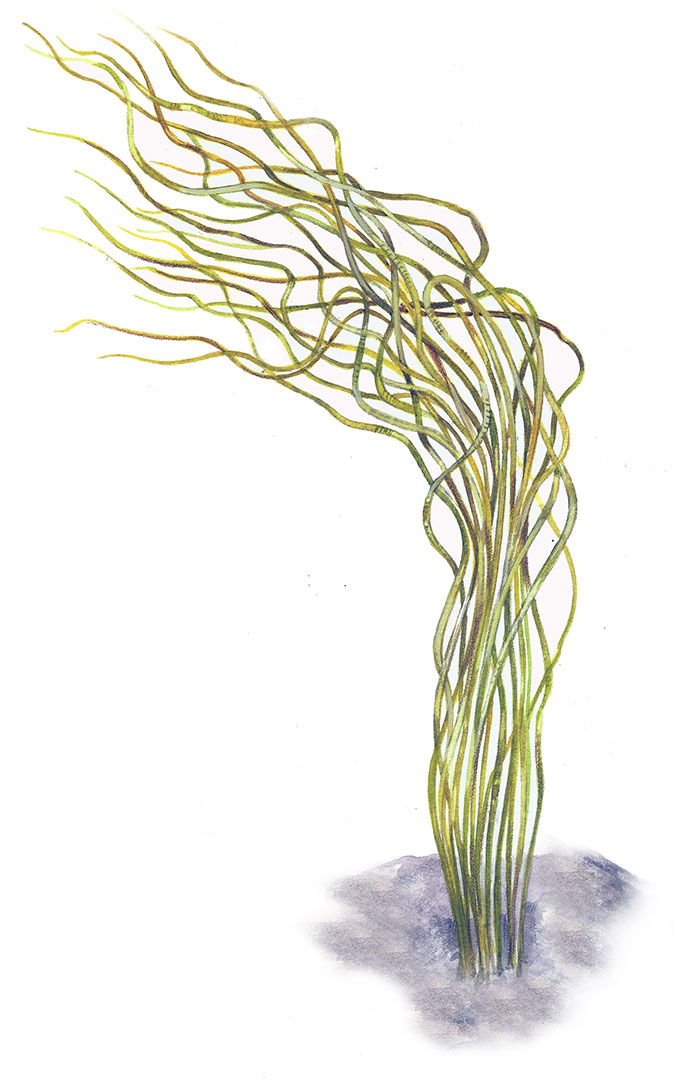

Thongweed Phaeophyta

(Himanthalia elongata)

Although this species is also known as ‘sea spaghetti’, I prefer thongweed because it brings those sea nymphs to mind. Thongweed forms dense populations that look like very coarse hair draped over the rocks at low tide. The long fronds are branched and 61⁄2ft long. They grow from mushroom-shaped structures of about 1in in diameter that are attached to the rocks. These ‘mushrooms’ are very often found on their own, causing confusion to those new to phycology. Thongweed is edible.

Furbellows Phaeophyta – aka kelp

(Saccorhiza polyschides)

A monster of a seaweed, it’s our largest at up to four yards in length. Remarkably for something so large, it is an annual. Furbellows is more splendid than beautiful. Its fronds form massive fingers that are attached to a flat ‘palm’, that, in turn, is attached to an arm with frilled edges. Like most seaweeds, Furbellows has a holdfast to fix it to rocks. It’s a massive, warty, inverted cup, which can form a habitat for small marine creatures.

Nearly all kelps are ecologically important for another reason – they form extensive kelp forests. An important ingredient in miso soup is something called kombu. Like a bayleaf, it’s removed after cooking, its flavour-enhancing glutamates left behind. Kombu is another kelp species, but Furbellows is identical for culinary purposes. I hang it and other kelps on my washing line to dry, a habit that’s cemented my reputation for being a bit odd.

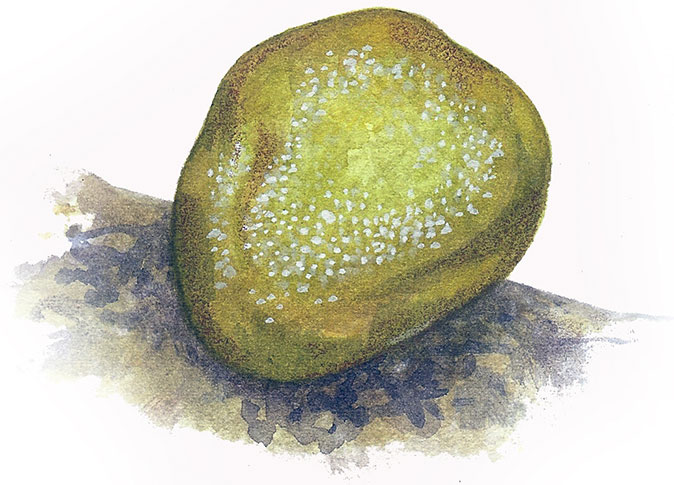

Oyster Thief Phaeophyta

(Colpomenia peregrina)

This odd-looking seaweed – which is about the size and more or less the shape of a tennis ball – is not a native species. It came first to France, arriving with the cultivated Pacific oyster, then made its way to the south coast of England. Despite being a foreign introduction, it’s never caused any problems, just the little buzz of joy in seeing something so peculiar bobbing about in the sea.

And the common name? Well, it sometimes grows on oysters. When it gets to a certain size, its oxygen-filled body is sufficiently buoyant to lift the unfortunate oyster from the seabed and float off with it.

Laver Rhodophyta

(Porphyra umbilicalis)

The membranous brown fronds of laver can be found at low tide, covering rocks like discarded plastic bags. Impossible to eat raw, laver must be cooked for a heroic 10 hours. Only then will the cell structure break down to release the intense umami flavour locked inside. The result of all that cooking is a sticky, brown paste known as laver bread, which people either love or hate.

An almost identical species, Pyropia yezoensis, is cultivated in the Far East in the millions of tons. This is not used to make an oriental laver bread, but nori, the black papery covering of sushi rice. It was a difficult species to cultivate until breakthrough work by the English phycologist, Kathleen Mary Drew-Baker in 1949, when she published the life cycle of Porphyra species. This formed the basis of a multi-billion-dollar industry and Drew-Baker is honoured in Japan with a monument and the impressive title ‘mother of the sea’.

Dulse Rhodophyta

(Palmaria palmate)

Once considered an incomprehensible habit of the Celtic fringe, eating seaweed has now become very fashionable in Britain, if not exactly mainstream. The main issue is how you cook the stuff. Most seaweeds have special applications in the kitchen and you can’t simply boil them up. However, dulse is the exception because you can.

It can be boiled or steamed like cabbage and the result is very cabbage-like in appearance because the red fronds turn instantly green on cooking. And the taste is very similar if you forget the fairly strong flavour of iodine.

I eat about half a dozen seaweeds, but dulse is my favourite because it’s so versatile and, of course, it tastes good and is extremely nutritious. I collect about 65lb every year. What I can’t eat fresh, I wash and dry on my daughters’ trampoline in the garden. I dry it further to crispness in a low oven, then blitz it in a powerful blender until it’s nearly a dust. Sprinkled on scallops or sea bass, it beats any fancy sauce.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.