A new ode to Spring, from gambolling lambs to pale wood anemones and the rabbity-nosed velvet of ash buds

Once believed to be summoned from slumber by birdsong, spring is a season of timeless joy for John Lewis-Stempel.

Very old are the woods; And the buds that break Out of the brier’s boughs When March winds wake, So old with their beauty are — Oh, no man knows Through what wild centuries Roves back the rose. — Walter de la Mare

Spring is a timeless joy, whether you are girl or boy. It is a pleasure democratically available to all, dweller of city flat, country hall. Spring! Gaudy yellow cowslips trumpet the news. Spring! A word enough to make the heart sing. Spring! When trees unfurl their leaves, butterflies their wings. Spring! When the birds again sing.

Some of my favoured things of spring are commonplace, which is part of their delight — to know that, since the Stone Agers penetrated these isles’ wildwood, we have delighted in them. I adore with the commitment of a disciple the thrush singing matins against April’s celestial blue mornings — as pure as the first day of Creation — and the rabbity-nosed velvet of ash buds.

In spring the sap rises, as surely as increasing sun rises the spirits. The fancy of animals turns to fecundity, the thoughts of farmers to spring wheat, but it is all the planting of seed. The birds do it, the bees do it, humans too. According to the Bard in As You Like It:

It was a lover and his lass, With a hey, and a ho, and a hey nonino That o’er the green cornfield did pass In spring time, the only pretty ring time When birds do sing, hey ding a ding, ding, Sweet lovers love the spring.

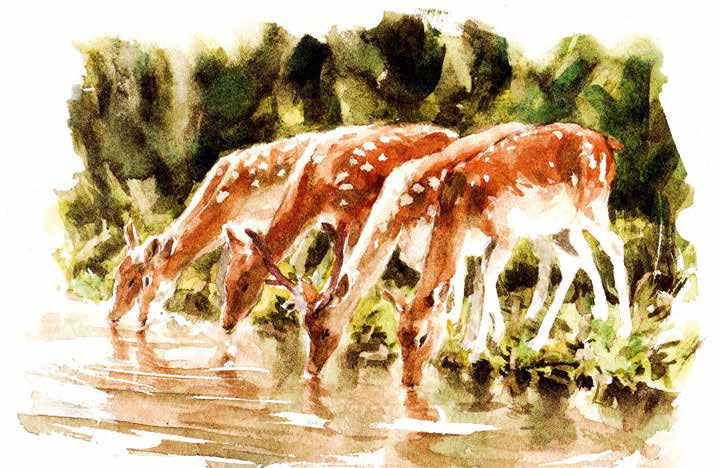

How keenly we look for them, the signs of spring, which come all in a rush, like a list, read rapidly: gambolling lambs in meads, fat trout in brooks, slow-worms sunning on stones, titlarks bleating zee zee in Evesham pear orchards, curlews soaring over high Yorkshire moors crying curlee, blackbirds laying their bluey-green eggs (real Easter eggs!) in Sussex hedges still bare and ruined by winter.

Sometimes, through the March woods, a cold blast comes, a last clutch of winter’s leonine clees, what we in the country call a ‘blackthorn winter’, because it stimulates the sloe tree into white blossom, a lampooning of winter’s snowy mane. Then, suddenly, copses boom with the clarinet cu-cu of the cuckoo, favoured announcer of spring of every poet, ever. For Spenser he is ‘merry Cuckow, messenger of Spring’, for Wordsworth a welcome ‘darling’ — the bird seen, but never heard. Traditionally, he arrives on St Tiburtius’s Day, April 14, yet may not reach bonnie Scotland until April 24. He carries spring up Britain on his back.

The cuckoo and the nightingale, mellifluous and melancholic the latter, get the poets’ chatter, but spring’s truest herald is the chiffchaff, that tiny bundle of feathers that battles the weathers to return to his particular tree. Chiffchaff’s rusty squeak would grate the nerves if he were not so brave-hearted, so bell-clear in his good tidings above March’s rude wind — ‘It is spring!’ The chiffchaff is the guarantee that spring will come.

By May, the chiffchaff will be joined by warblers many — 12 million songbirds come here in the ‘great arrival’ — steering magically by the stars to join the crescendo in the dawn chorus. The avian aubade in May is Nature’s musick that poor musicians seek to imitate, were they but birds themselves.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Deep in the wood, now going on green, the woodpecker drums on the stag-headed oak and the trees echo with his bass percussions, to the bemusement of the blue-eyed fox cubs playing at the scrappy entrance to their earth. As for flowers, who isn’t happy to see the frail, pale wood anemones illuminating the forest floor, which the rains of winter made mire?

And then every bowery corner reverberates with birdsong, is blurred by lines of darting birds making eggy nests. Winter is slow monochrome film; spring is fast colourised cinema. Spring is always beautiful, always the victory of the jeunesse dorée (fashionable and wealthy youngsters). As snaily-paced aging takes us over, so we value our springs the more. They are our well-spent youth, our prayer, our hope, our rebirth, our resurrection, our life to come.

The pace of spring quickens more! Of the butterflies the brimstone is first afloat, hesitant yet carefree, testing the temperature, reassured flies all about, a travelling spot of sunshine wherever she goes. The buzzy bee in her heavy stripy fur coat is better wrapped against late frost as she house-hunts in the hedge bottom (where she disturbs the slumbering spiny hoglet). Above the suburban back lawn, just mown — first time this year — gnats dance in faerie fountains.

Spring! A world in motion.

Over the growing grass of the meadow — I could revel in it, roll in it! — blow sweet primrose breezes. Cuckoo flowers nod their pale-pink heads in approval. The lambs born, my shepherds’ main duty done, in the soft arms of evening, I watch the child-sheep play king of the castle on the long-dead, fallen-over trunk of elm, as weather-whitened as bone. In warmer air, lengthening days, they, too (the farm animals), know the happiness of spring. Of sun on the back.

Up in the sky, larks mount the celestial blue to remind us of our lexicography: ‘spring’ is from the Old German spryng, to ascend. In meads rioting with floral colour (red clover, the white version, too, and speedwell’s blue) hares box, the girl fighting off the suitors, fur flies under the neighbourly chatter of swooping swallows, here for the springtime eruption of insecty things. The elevating drone of a billion gauzy wings is as much the sound of spring as the turtle dove’s cooing.

We, the creatures on two legs, have our own salad days in spring. My mother, a Herefordshire farmer’s daughter, picked hawthorn leaves (‘bread and cheese’) from the lane hedge on the way to school. Is anything lovelier than a country lane in spring? The way the verge-side flowers tone, both with each other and with the bright green grass. Yellow dandelions, red campion and delicate white stitchwort under doily cow parsley, already beginning to reach out over the tarmac.

Mind, I think it is at the pond that spring is to be seen at its most elemental. The verdancy of the willow’s wands is perhaps its earliest proof. Ramsons, in the lee of alder, are potent as smelling salts. Wake up, ’tis spring!

Under water dotted in rings of beauty by April’s rainbow showers, the male stickleback in full fig — red belly and blue eyes — stakes a fiefdom, just as the birds of the air do, just as humans of the Earth do. (March, named for Mars, God of War, was the beginning of the Roman military calendar.) The desperation to breed is most acute in the toad, which emerges from winter hibernation, that living death, to mate with indiscriminate, mewing frenzy in the ancestral pond.

What is the prompt that wakes the toads, bluebells, the Daubenton’s bats in their hollow ash tree on the cote of the pool? Scientists aver it is 6˚C-plus on a mercury gauge and the ‘photoperiodic (light-time) switch’. Longer, lighter days in plainer words. Personally, I like the medieval idea, that spring is summoned from its sleep by the singing of the birds.

The best prose, poetry and music of spring

- John Clare — I love the little pond to mark at spring

- George Orwell — Some Thoughts on the Common Toad

- William Shakespeare — Sonnet 98

- Rev Gilbert White — The Naturalist’s Journal, February–May, 1780

- Richard Jefferies — Hours of Spring

- Robert Browning — Home-Thoughts from Abroad

- Gerard Manley Hopkins — Spring

- Claude Debussy — Printemps

- Igor Stravinsky — The Rite of Spring

- Frederick Delius — On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring

Credit: Getty

Snow, rubber gloves, lubricant gel... and moments of wonder and joy: The reality of lambing in winter

John Lewis-Stempel's dispatches from lambing season focus on the early March snows which made a tough job into an battle.

Credit: Philip Bannister / Country Life

The extraordinary writing which made John Lewis-Stempel Columnist of the Year

Read three of the beautiful, evocative articles which made Country Life's John Lewis-Stempel the Columnist of the Year.

Credit: Guardians of the Forest, Llanrhychwyn, Snowdonia, Wales ©Simon Baxter / Landscape Photographer of the Year

A walk in the woods: Tranquility, beauty, and a 500,000-year-old connection to our ancestors

John Lewis-Stempel appreciates the calm tranquillity of woodland as he wanders through his own treasured Cockshutt Wood.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

In praise of nightingales: 'I’ve listened to Gregorian chants in Gothic cathedrals — but the greatest musical performance I ever heard was outside my bedroom one night'

It’s 200 years since Keats penned ‘Ode to a Nightningale’, but this otherwise drab bird’s rich, sorrowful song is worth

In praise of ponds, the water havens that 'teem with life as fantastic as anything in science-fiction'

A chance reading of George Orwell brought John Lewis-Stempel to the realisation that he'd neglected his own ponds. He explains

-

How many bees, Channel 4 and a Catch 22: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 6, 2025

How many bees, Channel 4 and a Catch 22: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 6, 2025Tuesday's Quiz of the Day features a famous road, nature and science.

-

Tasburgh Hall: From a Buddhist centre to a seven-bedroom family home in 23 acres

Tasburgh Hall: From a Buddhist centre to a seven-bedroom family home in 23 acresThe property, in Norfolk, was once four separate apartments, but has been lovingly re-stitched back together.