A complete guide to the sharks you'll find in the seas of Britain (and the one you'll be glad isn't here yet)

From elusive angelsharks to chunky, sprinting shortfin makos and glow-in-the-dark velvet belly lanterns, award-winning marine biologist Helen Scales gets up close and personal with the sharks that swim in British waters.

The words baby shark may have you humming a maddeningly catchy tune for the rest of the day, but they transport me to a Devon beach and an up-close encounter with the most adorable shark I’ve ever seen. A small-spotted catshark, it was swimming lazily around a rock pool. Roughly the size of a cigar, it was covered in speckles and it must have only just hatched out of its egg case, where it had been wriggling and growing for close to a year. I couldn’t resist picking up the little shark for a moment and gently holding it in the palm of my hand.

Britain is not renowned for its sharks, yet, beneath the waves, there’s a rich mix of species. The tiny catshark I found is one of 21 kinds known to reside full time in UK seas. An additional 40 or so arrive each year as seasonal visitors. Together, they range from deep-sea oddballs and plankton-sifting giants to super-fast sprinters and flattened seabed sitters.

All of them are members of the same group of fish, known as elasmobranchs, the direct ancestors of which have been swimming around the ocean for at least 400 million years. It’s generally easy to spot a shark from a bunch of other fish. They have a characteristic bendy skeleton and jaws that are made not from hard bone, but cartilage — the same soft material from which human noses and ears are made. Sharks don’t have scales either, but skin covered in tiny teeth-like structures, called denticles, which makes them smooth if you stroke them from head to tail and rough like sandpaper in the other direction.

Greenland sharks

Compared with many other fish, these marine predators tend to be very slow growing and long lived — one of their number is thought to be the oldest animal on the planet, the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus), which can live for more than 400 years.

Some, such as the small-spotted catsharks (Scyliorhinus canicula), lay eggs; others give birth to live young after pregnancies that can last for up to two years. Unfortunately, this unhurried pace of life puts many sharks at high risk of overfishing. Globally, one-third of all shark species (and their close cousins the rays) are threatened with extinction.

Basking sharks

The stereotypical idea of shark is a grey, torpedo-shaped predator, like the great white, but, as the British species show only too well, there’s far more to these fish than a huge mouth full of teeth. Biggest of all, at up to a London bus-sized 39ft long, are the basking sharks (Cetorhinus maximus), which have minute teeth that are no good for hunting, but are probably used in mating rituals, when males hold onto females by biting their fins.

Basking sharks arrive in the UK each summer to feast on soupy blooms of plankton, using special organs on their gills to sieve the sea. They were formerly hunted for the vitamin-rich oil in their enormous livers and their populations were devastated. Now, they are strictly safeguarded around the UK, including off the Outer Hebrides in Scotland, where the world’s first marine-protected area was set up specifically for basking sharks.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Blue sharks

Another seasonal visitor is the blue shark (Prionace glauca), which migrates thousands of miles across the ocean, cruising with its sleek, steely-blue body and long pectoral fins.

Shortfin mako sharks

Shortfin mako sharks (Isurus oxyrinchus) also occasionally show up, looking like chunkier versions of blue sharks, only with bigger eyes and snaggletoothed jaws: a swimming powerhouse, they are faster than any other shark, with top-speed bursts of more than 45mph.

Thresher sharks

Thresher sharks (Alopias vulpinus) are spotted now and then off British coasts. Their bodies can be up to 19½ft long, with half of that being made up of their impressive, scythe-shaped tail, which they whip over their heads to stun shoals of fish.

Starry smooth-hound shark

Starry smooth-hounds (Mustelus asterias) are a more common sight — anglers regularly catch them around British coasts and know how to release them alive carefully.

These are small sharks, usually about 4ft long, with delicate grey skin speckled with white spots. They live in shallow water, mainly in the south and west, and seem to be moving further north.

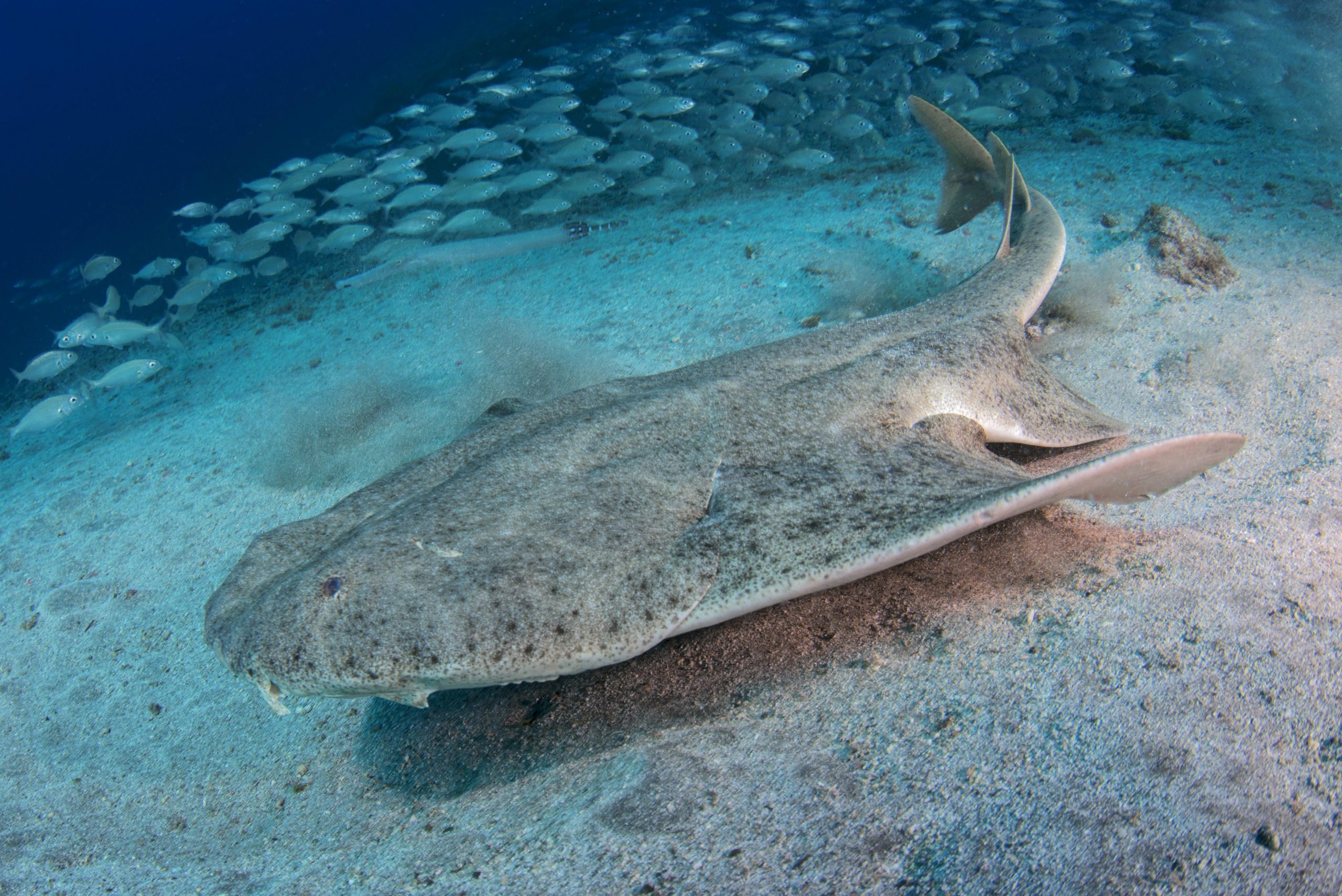

Angelsharks

One enigmatic shark species was for a long time thought to have completely disappeared from British waters due to overfishing. Angelsharks (Squatina squatina) used to be caught and sold in the UK as monkfish, until numbers collapsed in the mid 20th century.

Recent studies have shown that angelsharks are still around, in particular off the coast of Wales, but they are not easy to spot in the wild. They are flat and lie still on the seabed, partially buried in sand, waiting for hapless prey to wander by. Scientists working closely with anglers and fishermen have learned that angelsharks are still occasionally getting caught and have found fragments of DNA in sea-water, which indicate that live angelsharks must have recently swum by (DNA quickly breaks down in the environment). In 2021, diver Jake Davies filmed a young angelshark in Cardigan Bay, proving that females are using these waters as a nursery area. Now the species has been brought back from obscurity, conservationists are working on plans to protect the survivors and rebuild their numbers.

Blundnose and Sharpnose sixgill and sevengill sharks

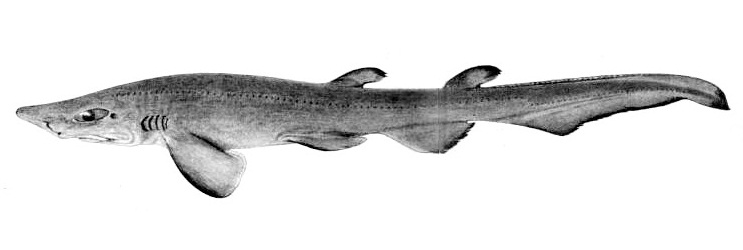

The strangest British sharks are the ones that live a long way beneath the waves.

Among the deep-sea denizens are species that don’t have the sharks’ conventional five-gill slits on the wide part of their bodies, but one or two extra — the bluntnose sixgill (Hexanchus griseus) and sharpnose sevengill sharks (Heptranchias perlo).

Frilled sharks

Another six-gill creature is the frilled shark (Chlamydoselachus anguineus), which has a long, chocolate-brown body, like an eel, and odd three-pointed teeth.

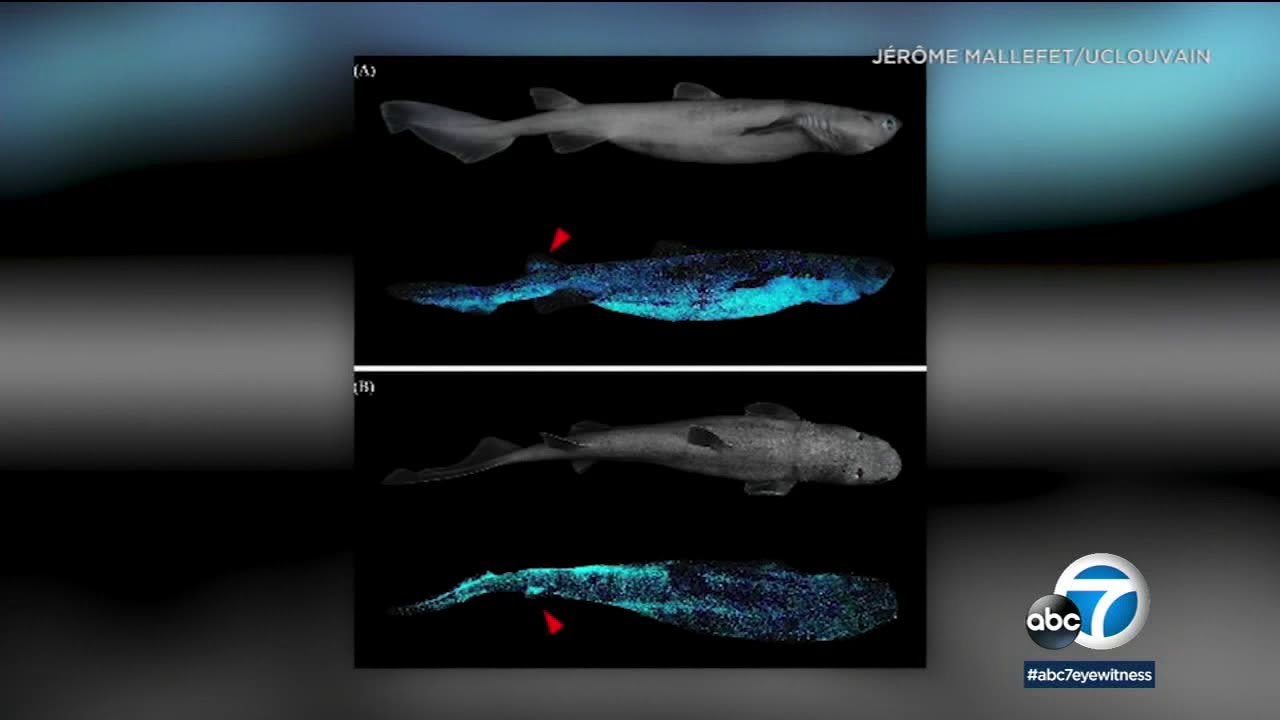

Velvet belly lantern sharks

Swimming through deep UK seas, mostly in the far north-west, are several sharks that glow in the dark. Velvet belly lantern sharks (Etmopterus spinax) have black skin with shining spots on their bellies that emit a dim blue light.

These lights hide the shark’s dark silhouette when seen from below, helping them to sneak up on prey and avoid being spotted by predators.

Kitefin sharks

Kitefin sharks (Dalatius licha) are the world’s largest known bioluminescent sharks, at close to 6½ft long. It’s possible they use their belly lights to illuminate the seabed to hunt for prey as they slowly swim along.

Mouse catsharks

Mouse catsharks (Galeus murinus) were given their delightful name on account of their small size. Fully grown individuals don’t get much bigger than 1½ft or an arm’s length.

They are members of the same family as the small-spotted, with similar oval-shaped, cat-like eyes, but there’s no chance of coming across one in a tide pool. They live on deep continental slopes, between 984ft and 4,265ft down.

Smalltooth sandtiger shark

This has been a bizarre year for sharks in Britain. In March, a smalltooth sandtiger shark (Odontapsis ferox) was spotted alive off the coast of Hampshire and a swimmer pulled it back out to sea, hoping it would swim safely away. Sadly, it was later found dead on the beach and it sparked a race to secure it for science. This species of shark has rarely, if ever, been seen in this part of the world. Normally they’re found much further south in warmer seas.

Television historian Dan Snow lives close to Lepe beach, where the shark washed up, and, when he heard about it, he dashed home from London. By the time he arrived, trophy hunters had already cut off and taken away the head and tail. Mr Snow made a public appeal for the return of these rare shark body parts so scientists could study them.

But that was only the start of the sand-tiger-shark affair. In April, a massive, 13ft specimen was found on a beach in Co Wexford, Ireland. Another appeared a month later, floating dead in Lyme Bay, off Dorset. Scientists are still wondering why this trio of rare sharks showed up so near each other. It could be that warming seas are drawing the species further north. Why these ones died also remains a mystery.

Are Great White Sharks and Tiger Sharks ever found in Britain?

Elsewhere in the ocean, these predators are responding to climate change and shifting their ranges — not least great white (Carcharadon carcharias) and tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier), which are migrating further north along the coasts of the US.

Despite numerous reported sightings of great whites (above) around the UK, there’s no concrete evidence that they’re inching closer to these shores.

This poses another puzzle, because conditions here are right for them. In the summer, the seas are their preferred temperature (about 16˚C) and there are plenty of harbour and grey seals for them to hunt.

Scientists are not entirely sure why great whites haven’t obviously moved into British seas and they’re keeping a close eye out for any that might arrive.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr Helen Scales is a marine biologist, writer and broadcaster. She is author of many books about the ocean including the Guardian bestseller Spirals in Time, New York Times top summer read The Brilliant Abyss and the children’s books What a Shell Can Tell and Scientists in the Wild. She writes for National Geographic Magazine, the Guardian, and New Scientist, among others. She teaches at Cambridge University, is a storytelling ambassador for the Save Our Seas Foundation and science advisor for the marine conservation charity Sea Changers.

World’s first protected area for basking sharks to be set up in Scotland

Scotland wants to create the world’s first protected area for basking sharks

If you go down to the beach today... be careful not to step on a potentially-deadly jellyfish

Look, but don't touch — large numbers of colourful Portuguese man o' wars have been stranded on the UK coastline.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025Wednesday's quiz tests your knowledge on literature, National Parks and weird body parts.

By Rosie Paterson