Why conservation must start at home: 10 British species we need to save to protect our food chain

Simon Lester sends out an SOS for 10 species that we must save to help repair an increasingly fragile food chain.

We tend to get excited about creatures at the top of the food chain, but the frightening truth is that they’re dependent on the flow of energy that ripples up from the plants at the bottom to the apex predators.

It’s this delicate, complex thread that’s under threat because once-common species are rapidly dwindling. Here, we single out 10 species that were far more common 50 years ago, which we should be worrying about.

Common frog

Rana temporaria

Watching the metamorphosis from tadpole to froglet has thrilled many a young naturalist. However, as the common frog has been in steady decline since the 1970s, it’s getting harder to find frogspawn in some areas — often the only indication that frogs are present, as they’re secretive creatures that mainly feed at night on insects, worms and slugs.

Song thrush

Turdus philomelos

This songster belts out its flute-like tones, but a subtler and more sinister sound gives away its presence: the tap, tap, tap of a snail shell being hammered home on the bird’s stone anvil.

These natural sites of industry are becoming rare and, as the snails disappear, so do the thrushes, with their beautifully constructed nests containing four or five bright-blue eggs embellished with black spots.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Sawflies

Symphyta

The 500 species of sawfly have been a valuable food source for some 250 million years. They’re way down the food chain — they’re food themselves — and adults only live for nine days. Their larvae appear at the right time to fuel a productive spring and summer for birds and other creatures. The female lays her eggs in their specific host plant via a saw-like ovipositor, hence the name.

They’re a major pest — they communally and systematically strip each leaf — but their decline on farmland, due to increasingly effective insecticides, has had a major impact on the wild grey partridge.

Skylark

Alauda arvensis

The presence and crystal-clear song of this little brown job on arable or downland brightens anybody’s day, but larks are food for raptors — notably the hen harrier — and, as ground-nesters, they’re also hoovered up by badgers and foxes.

Although adult skylarks devour seeds and invertebrates, their young depend on an insect diet. One reason for their decline is that modern cereal crops are too thick for them to nest in; some farmers turn off the drill to leave small bare plots for access.

Sweet violet and common dog violet

Viola odorata and Viola riviniana

There are 10 species of violet in the UK, but the only one with a scent is the exquisite sweet violet. They’re disappearing from hedgerows due to denser, suffocating grass, the result of misdirected fertiliser, which is worrying as they’re an important part of the lifecycle of several fritillary butterflies and critical for the small pearl-bordered fritillary, as only violet leaves sustain the caterpillars.

Glow-worm

Lampyris noctiluca

When I first saw the strange, bioluminescent light that the rather drab female glow-worm emits from her tail in summer months, I had to look twice to check that I wasn’t going mad, but the enchanting phenomenon is another of Nature’s efforts to attract a mate in the shape of a slim brown beetle, rather than a worm.

However, I suspect that children lulled to sleep by glow-worm-effect night lights would have nightmares if they knew the Dracula-like feeding methods these beetles deploy in order to kill and dissolve their favoured prey of snails and slugs.

Rabbit

Oryctolagus cuniculus

They were brought to Britain by the Romans to feed us, but soon became a staple for several predators. They also quickly became a serious agricultural pest, sculpting the edges of cornfields and allowing arable weeds to thrive. Intensive rabbit grazing of down and heathland gave other plants and invertebrates an opportunity to exploit this niche situation.

However, now that numbers are plummeting due to viral haemorrhagic disease, a massive chunk of biomass is missing from the food chain, which will impact on other species.

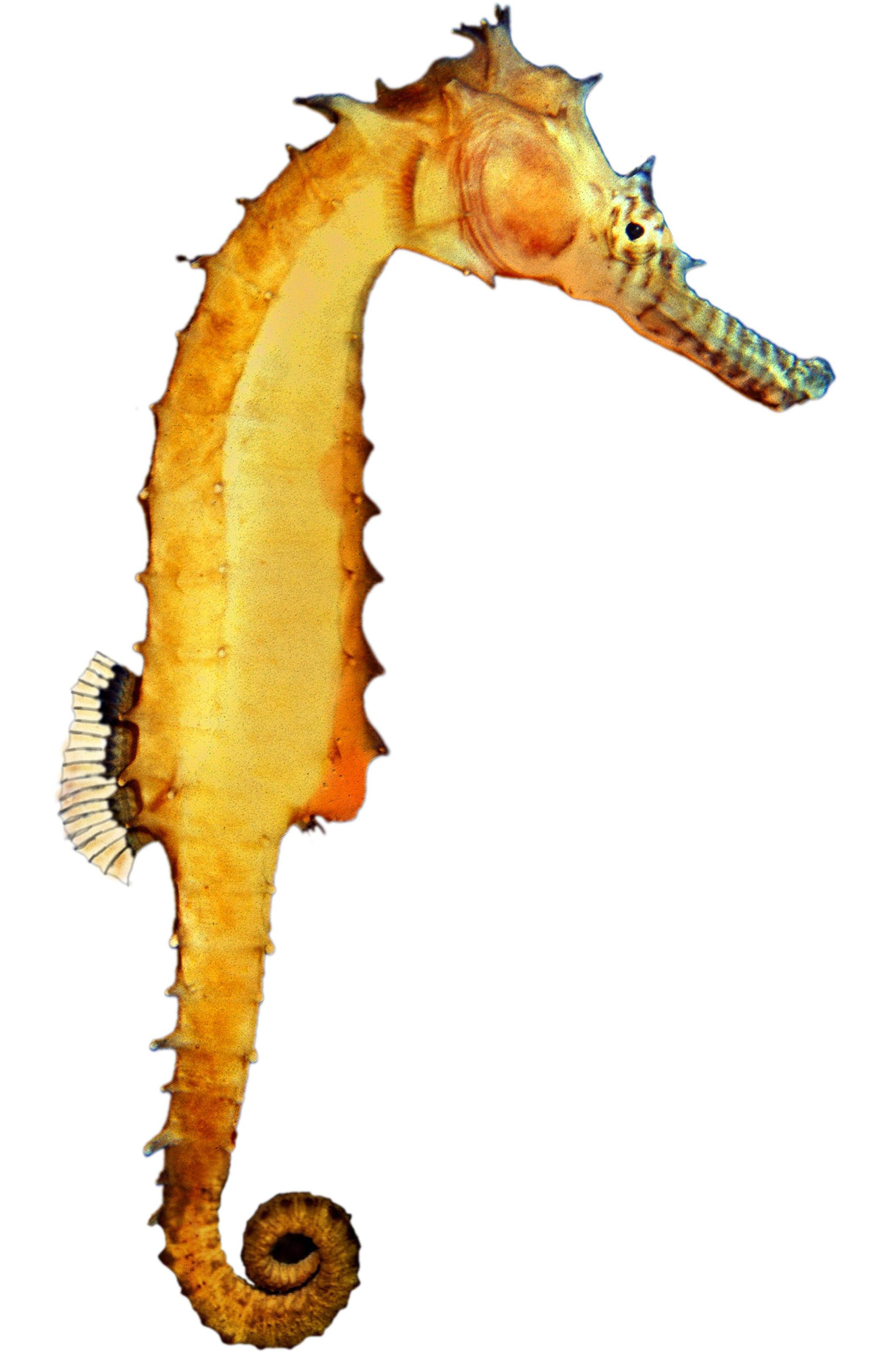

Spiny seahorse and short-snouted seahorse

Hippocampus histrix and Hippocampus hippocampus

These two types of seahorse need such a pristine seabed to thrive that their presence indicates a healthy habitat, often including eel grass. Poor swimmers, they use their tails to anchor themselves to the weed, while sucking up food through their trumpet-like mouths.

Arguably one of our most politically correct creatures — they mate for life and the male both incubates and gives birth to the young after receiving the females’ eggs — their numbers have dropped alarmingly in the past 10 years. Studland Bay in Dorset is believed to be the only place where it’s still possible to see both species.

Cowslip

Primula veris

It’s still possible to enjoy grassland studded with their nodding yellow heads, but only in places where they’ve been nurtured. If they thrive in spring, it’s a good indication that there will be a floristic treat throughout summer, as other rarities have their time.

With a sweet perfume, they provide an early source of nectar for many insects and are the primary food plant for the Duke of Burgundy butterfly.

Three-spined stickleback

Gasterosteus aculeatus

This diminutive but pugnacious fish provides a tasty snack for a wealth of species higher up the food chain, from kingfishers to pike. These tiddlers have long entertained children, for whom finding them while dabbling in a stream might be their first hands-on experience of Nature.

The three-spined stickleback positively glows at spawning time, when males build nests and adopt a bright-red belly, with complementary bright-blue eyes.

Credit: Alamy

The six types of owl you’ll find in Britain

Gamekeeper Simon Lester offers his guide to these mesmerising creatures, from the pocket-sized Little Owl to the fearsome Eagle Owl

Credit: Getty / Duncan Usher / Minden Pictures

Beware the Great Grey Shrike: The pretty songbird with the temperament of Vlad the Impaler

Simon Lester takes a look at the great grey shrike, a delicate-looking songbird whose innocent appearance belies its sadistic tendencies

Britain’s birds of prey: The Country Life guide to all of the UK’s raptors

Raptors’ supersonic vision, effortless aerial acrobatics and ruthless hunting instinct make them the undisputed masters of the skies, but can

Curious Questions: One for sorrow, two for joy – but why are we so superstitious about magpies?

Superstitions swirl around all manner of different birds, but never more so than with magpies. We take a look at

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?The team behind London's first mixed-use ‘wellness village’ says it has the magic formula for tempting workers back into offices.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

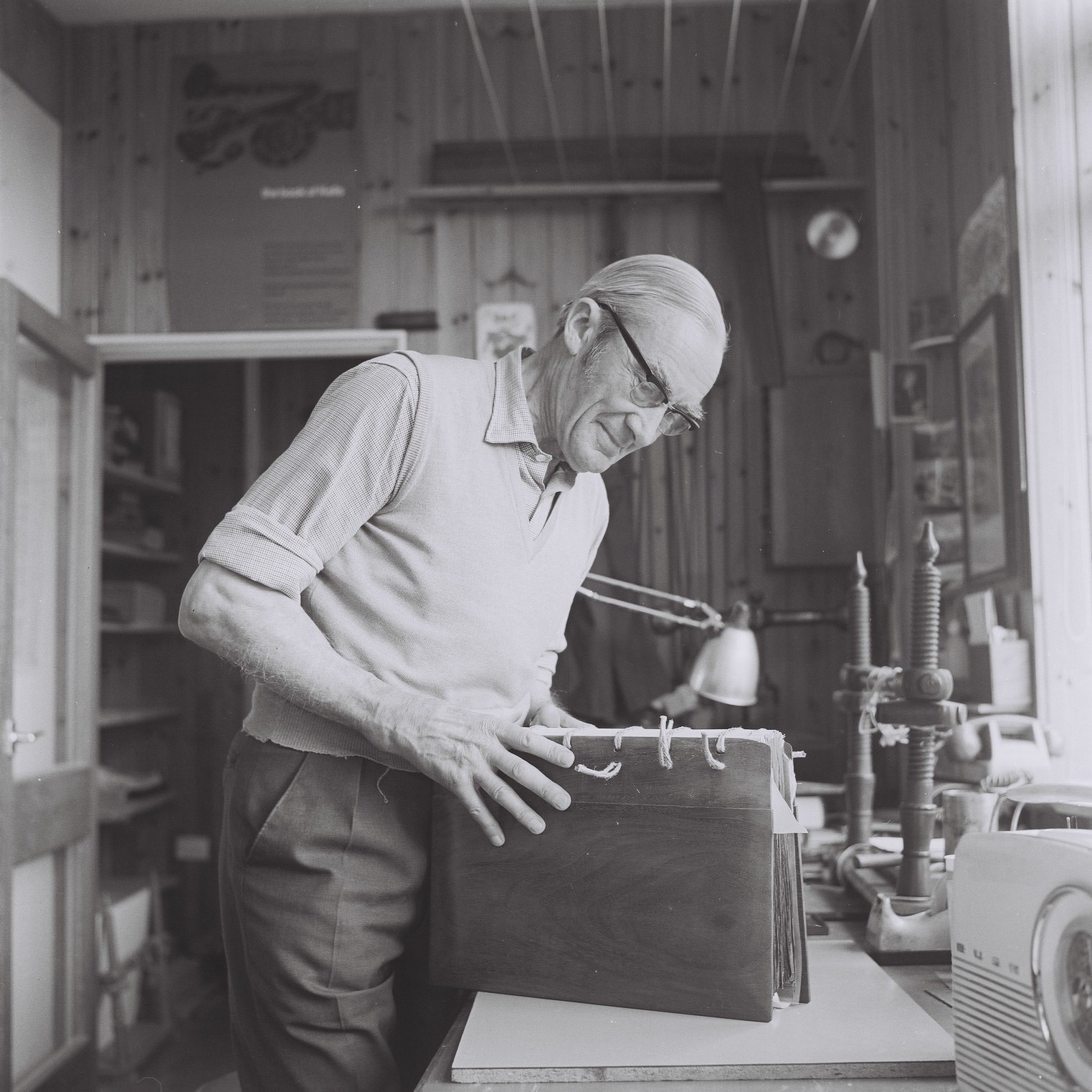

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comeback

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comebackThe Kentish glory moth has been absent from England and Wales for around 50 years.

By Jack Watkins

-

The birds of urban paradise: How to get twitching without leaving the city

The birds of urban paradise: How to get twitching without leaving the cityYou don't need to leave the concrete jungle to spot some rare and interesting birds. Here's a handy guide to birdspotting in Britain's towns and cities.

By Richard Smyth

-

Food with a pinch of salt: The crops we can harvest from the sea

Food with a pinch of salt: The crops we can harvest from the seaFilling, rewarding and nutritious, vegetables and plants grown in saline environments — whether by accident or design — have plenty of potential. Illustration by Alan Baker.

By Deborah Nicholls-Lee

-

White-tailed eagles could soon soar free in southern England

White-tailed eagles could soon soar free in southern EnglandNatural England is considering licensing the release of the raptors in Exmoor National Park — and the threat to pets and livestock is considered to be low.

By Jack Watkins

-

Britain's whale boom and and the predator that's far scarier than a great white shark, with wildlife cinematographer Dan Abbott

Britain's whale boom and and the predator that's far scarier than a great white shark, with wildlife cinematographer Dan AbbottThe wildlife cinematographer Dan Abbott joins us on the Country Life Podcast.

By Toby Keel

-

'They are inclined to bite and spray acid to protect territory': Meet the feisty red wood ant

'They are inclined to bite and spray acid to protect territory': Meet the feisty red wood antBy Ian Morton

-

The King wants YOU: His Majesty's call-to-arms for under-35s across Britain

The King wants YOU: His Majesty's call-to-arms for under-35s across BritainThe King’s Foundation has launched its ‘35 under 35’ initiative — a UK-wide search for ‘the next generation of exceptional makers and changemakers’ who want to work holistically with Nature.

By Amie Elizabeth White

-

'A big opportunity for a small, crowded and beautiful country': Fiona Reynolds on how the Land Use Framework can make Britain better

'A big opportunity for a small, crowded and beautiful country': Fiona Reynolds on how the Land Use Framework can make Britain betterThe Government’s Land Use Framework should be viewed as an opportunity to be smarter with our land, but conflicts need to be resolved along the way says Fiona Reynolds, chair of the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission.

By Fiona Reynolds