How many of today's best watches are inspired by the great watches of the past

Retro-inspired wristwatches will endure says Robin Swithinbank, as he charts the timepieces looking both backwards and forwards.

A few months back, I met a retired Austrian gentleman who was in the UK visiting his sister-in-law, a friend of mine. I’m sure she introduced him and told me his name, but, honestly, I wasn’t listening. Rather than respond with my name or even the simple courtesy of a hello, I asked him whether on his wrist that was indeed an original Omega Speedmaster MkII, a watch I happen to be partial to, but had never seen in the wild.

It was. He’d bought it in the early 1970s, not because he was working for NASA (we’ll get to that), but because, as he said with familiar watch-buyer economy, he liked it. He kindly removed it and allowed me to admire its almost seamless barrel-shaped case, its punchy reddy-orange dial detailing and the now smooth and slightly loose links of its metal bracelet.

This, as I reminded him, was the watch Omega that designed for Apollo astronauts to wear on the moon, unlike the Speedmaster Professional, affectionately known as the Moonwatch on account of the fact it actually went to the moon — unlike the Speedmaster MkII, which never did. Something to do with astronaut superstition, a retired NASA engineer once told me.

He knew this, of course, but seemed pleased to have someone to talk to about it, even if I’d clattered through our formal introduction only moments before, eyes squarely on his wrist. What I didn’t know, this being his watch, was that in five decades of ownership, he’d only had it serviced once, yet there it was, still ticking away accurately enough. Omega’s mechanical watches of the 1970s were that good.

I have no tangible connection to the MkII. My parents hadn’t even met when it was made. Yet, having discovered the story behind it in 2014 when Omega re-released it (sadly, without meteoric success), it has become a watch I’d gladly own some day. Why? I’m not entirely sure. I suppose I like the look of it and I do rather enjoy the strained irony hidden in its story (its case shape was designed so it wouldn’t catch on and tear a spacesuit. Useful, you’d think). I like the fact that few people know about it and that it has enormous icebreaker power, as this insouciant little anecdote suggests. As yet, I don’t own one, but the truth is, I’d as happily own the revival piece as the original, no matter how serviceable those retro pieces have proved. To my mind, the story and the aesthetic are wrapped up in both the old and the new.

I suspect as much is true of almost any revival luxury watch introduced over the past few decades — which is most watches. Since the 1990s, Swiss watch brands have been tearing through their archives in search of great designs, many finding rich pickings in their basements. TAG Heuer was among the first, asserting its new-found desirability that decade by reinstating the Carrera and the Monaco, both 1960s designs and now collection linchpins and industry archetypes.

Many others have played the same hand. You could pick Blancpain and its Fifty Fathoms; Cartier and its Santos; Tudor and its Black Bay; Oris and its Divers Sixty-Five; Vacheron Constantin and its newly minted Historiques 222; and many more besides. All watches with a vintage aesthetic plucked from the past and refeathered for contemporary audiences, who lap up the promise of design longevity and modern mechanics.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The biggest of the Swiss watch brands have made this regenerative approach an art form, basing almost their entire businesses on what they did before. Breitling’s growing popularity is hugely reliant on its ‘retro styles’, as it calls them, headlined by pieces such as the Navitimer (in constant production since the 1950s) and the Chronomat, an icon of the 1980s and 1990s (worn by Jerry Seinfeld) now doing good numbers for the company. Arguably, Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet paved the way here, the latter by recycling its lodestar Royal Oak again and again, constantly proved right in its hunch that the original luxury steel sports watch, penned by the great Gerald Genta in 1972, was a perennial winner.

Patek continues to rely on its back catalogue, too, most recently introducing the Ref 5172G chronograph, a watch that, with its syringe hands, bicompax dial and opaline rose-gilded dial, looks at first glance as if it should be the subject of bids in an Old-Masters-themed auction.

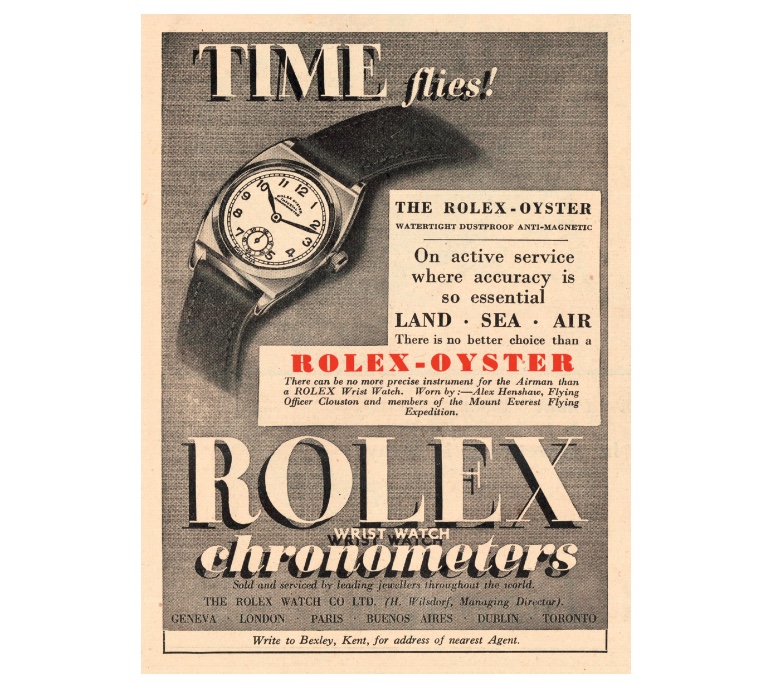

Rolex? Rolex is the nonpareil here. Wags quip that the green and gold superbrand only has one watch, reference to the fact its models are all basically the same shape, one it’s been peddling for generations. After all, despite the general list of Western contemporary mores, it’s perfectly possible that, if something was good once, it might still be good now. As Pierre Cardin reflected in later life: ‘My old vintage designs are so popular now. I must have been on to something.’ This year’s new Rolex Air-King, for example, is a borderline facsimile of the model it replaced. And the one before that, and so on. I hear no complaints.

Commercially, it seems, the persistent return to designs of yesteryear makes sense, but it’s tricky to determine what it is that keeps us coming back for more of the same, again and again. Novelty and innovation, we’re told, are the lifeblood of any business and watchmaking wouldn’t be afraid to say the same. There are countless brands, many of them small-scale independents, reinventing the horological wheel with convention-busting forms and bewildering mechanical movements, yet the large-scale luxury watch companies prefer to employ visual signposts to the past. Signs of innovation are likely to be tucked away in the small print explaining the materials and manufacturing techniques employed to ensure your new watch is up to the scrutiny of daily wear, not exposed in the designs.

Why? It’s only a theory, but my take is that the real lifeblood of the luxury-watch industry, the fuel that turbocharges it, isn’t game-changing evolution, but nostalgia. Nostalgia is the currency that keeps watchmakers solvent — and there’s nothing wrong with that. We only need open our newspapers to understand why a little Kodachrome-flavoured aspiration might be welcome. As John Steinbeck said with searing pathos: ‘In the souls of the people the grapes of wrath are filling and growing heavy, growing heavy for the vintage.’ If I might forgive myself, I imagine a nostalgic bent is also what led me to dispose of the pleasantries during that brief encounter back in the summer. What must life have been like when the fellow made his purchase? The intrigue will never be satisfied and so it remains. For such reasons, the vintage aesthetic isn’t going anywhere. Expect more of the same. This year. Next year. Always.

Five new watches inspired by the original classics

Rolex Air-King

Rolex created its Air-King in 1945 for the British RAF. At 34mm, it was large for the time, hence ‘King’. In the eight decades since, it’s become one of Rolex’s most-loved designs, which might explain why the silhouette of this year’s new model is so strikingly similar to the original. The typography on the dial is lifted straight from a model released in the 1950s with a new specification of 40mm, Oystersteel, £6,150 — rolex.com

Vacheron Constantin 222

Released in 1977 and designed by a young Jorg Hysek, the 222 was named for the years since Vacheron Constantin had been founded. It joined a growing roster of stainless-steel luxury sports watches led by Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak, but was discontinued in 1985 as the infamous Quartz crisis took hold. It only reappeared this year, this time in 37mm of gold. Historiques 222 in yellow gold, £60,500 (020–7578 9500; www.vacheron-constantin.com)

Patek Philippe Ref 5172G

Flick through the pages of any auction catalogue worth its salt and you’ll find Patek wristwatch chronographs dating back to the 1920s. The pure, frankly joyful aesthetic of those standard bearers continues to saturate the brand’s current chronograph collection, witnessed by this year’s white-gold Ref 5172G. £64,760 (01892 534018; www.gcollinsandsons.com)

Breitling Navitimer

Back in the early 1950s, before computerisation, wristwatches still had the power to be hugely effective tools. Breitling’s original Navitimer had a built-in slide rule for making all sorts of navigational calculations from the cockpit, assuming you knew how to use it. This year’s 70th-anniversary collection celebrated the design’s remarkable longevity. Navitimer B01 Chronograph 41 in steel on gold, with brown-alligator leather strap, £7,000 (020–3988 2224; www.breitling.com)

Piaget Polo

Yves G. Piaget knew how to work high society. His 1979 Polo luxury sports watch design was unashamedly aimed at those we now refer to as high-net-worth individuals and was frequently spotted on the wrists of luminaries of the time, including Andy Warhol and Björn Borg. The 2016 revival piece isn’t the spit of the original, but it’s become the brand’s bestseller. Piaget Polo Green Date, £25,300 (020–3364 0800; www.piaget.com)

-

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagne

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagneAn upwardly mobile spaghetti Bolognese, lasagne al forno, with oozing béchamel and layered meaty magnificence, is a bona fide comfort classic, declares Tom Parker Bowles.

By Tom Parker Bowles

-

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025Thursday's Quiz of the Day asks exactly how popular Baywatch became.

By Toby Keel