What's for sale on 'the most mouth-watering shopping list in Britain'?

A browse through the summary of works of art and objects of cultural importance with a deferred export license reveals plenty of treasures. What should we keep?

Do you fancy buying a Fra Angelico altarpiece? Now is your chance, as an example appears in the most mouth-watering shopping list in Britain. This is the regularly updated summary of works of art and objects of cultural importance for which the granting of an export licence has been deferred by the Minister for Culture, Media and Sport in the hope that a public institution or private individual in Britain will make a matching offer to acquire it.

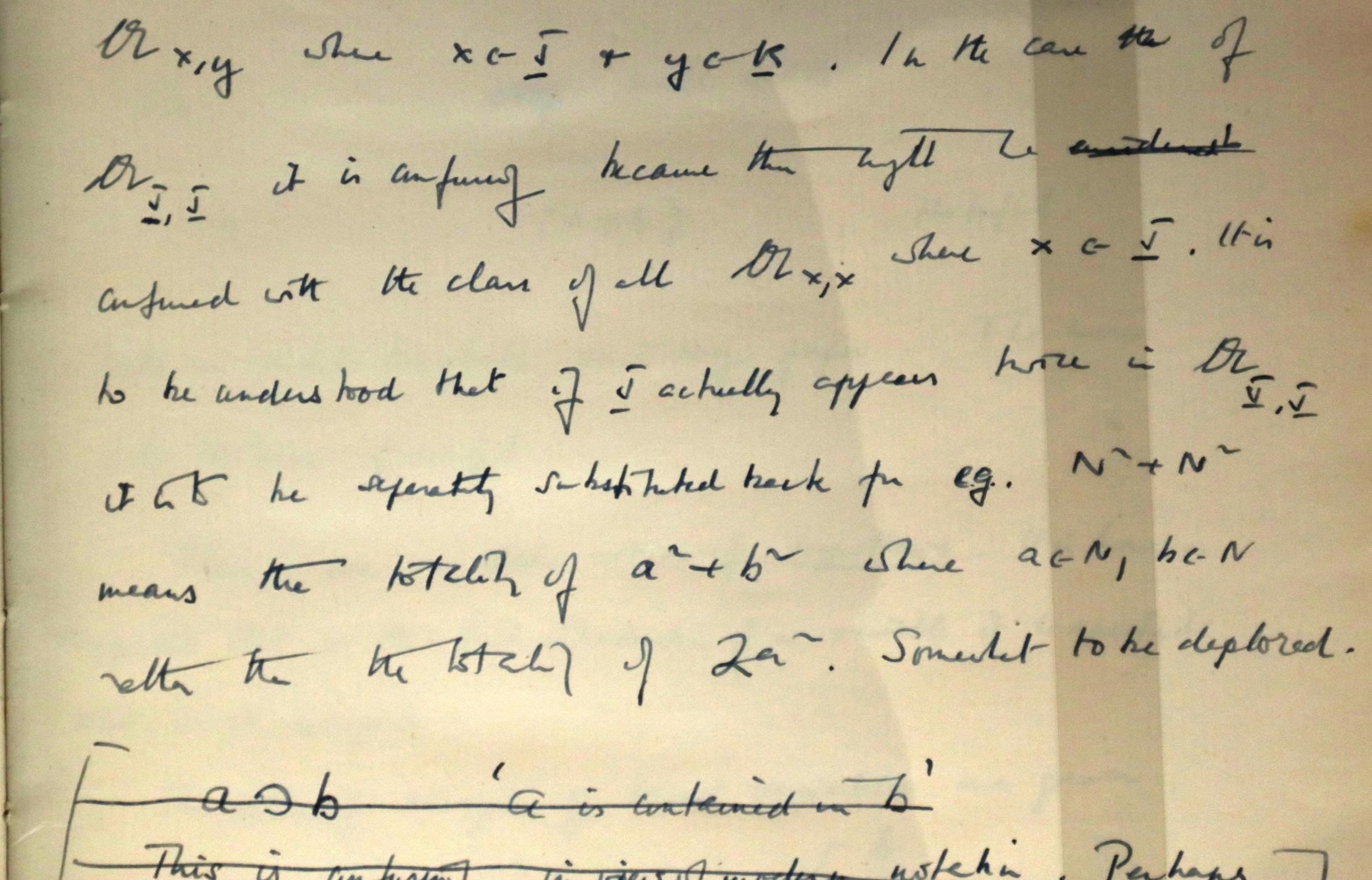

Usually only about one-third of the objects on the list are retained in Britain. The reason is principally cost: the Fra Angelico is valued at a shade over £5 million. Outside the fine arts, valuations are less intimidating: also currently awaiting a decision on an export licence are Alan Turing’s working notes for the Delilah Project, a portable encryption system — voice scrambler — for military operations, developed at the end of the Second World War, which are valued at £397,680.

There have recently been some successes at a challenging level of valuations; in July, for example, the V&A Museum raised £2 million for a superb fragment of an ivory Romanesque altarpiece. Given that cost is not — or not always — the sole issue, this raises the intriguing question of which objects are most likely to be retained.

For an export licence to be deferred, the object in question has to fulfil one or more of three criteria. Is it closely connected with our history and national life? Is it of outstanding aesthetic importance? Is it of outstanding significance for the study of some particular branch of art, learning or history?

In a speech in 2022 to mark the 70th anniversary of the present system of export controls, the then Arts Minister, Lord Parkinson, asked whether other factors might be taken into consideration. Is the work going to be acquired for public display abroad, for example? And might it have stronger connections with the country to which it would be exported?

These questions deserve discussion, but they would complicate a system that has the advantage of clarity. One might argue that the Fra Angelico would be better off in a museum in a country less well supplied with early Renaissance paintings than Britain, but that would fatally undermine the second criterion for deferral.

Turing is a figure of global significance, as well as a national hero. Therefore, it could be claimed that, for example, the National Library of Poland would also be an appropriate custodian of his papers given that country’s role in wartime code-breaking. In the end, it is a matter of gut instinct — it will seem to most people a national disgrace if the Turing papers leave Britain.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

There’s little time to lose: the period of deferral of their export licence ends on November 15; that for the Fra Angelico expires on October 29.

George Stubbs (1724–1806): Hero of the turf

George Stubbs, born 300 years ago, found Nature superior to art and approached his pictures with the eye of an

The Leonardo da Vinci masterpiece that never was, thanks to an assassination, a war, an abduction and an invasion

The great master Leonardo da Vinci was on course to create an equine statue that could have rivalled his greatest

James Fisher is the Digital Commissioning Editor of Country Life. He writes about motoring, travel and things that upset him. He lives in London. He wants to publish good stories, so you should email him.