Tonight we're going to party like it's 1929: A look back at Christmas Parties of the past

Office Christmas parties have been going on as long as there have been offices, but most of us have little idea about what once went on when our great-grandparents let their hair down. Recent discoveries, however, have unearthed some details of Country Life's Christmas parties of the past – John Goodall takes a look.

A century ago, in December 1918, Country Life was gearing up for its first grandly conceived Christmas party.

The timing was no coincidence. Not only had the magazine, which was founded in 1897, survived the war, but it had emerged from it an established and successful publication. It had also found its editorial voice and forged its crucially important advertising connection with the property market. In the intensely competitive world of magazine publishing at the time, this was a considerable achievement and marked a coming of age.

Frustratingly, however, we know nothing about the celebrations held in December 1918, other than that they took place. We wouldn’t even have known that if Elizabeth Blunt, the daughter of Fred Harden, a former Arts Editor of Country Life, had not contacted the magazine earlier this year and generously passed on some of her father’s papers. This gift, combined with an equally unexpected parcel sent from Australia in 2008 by Tony Noakes, the son of a former Country Life secretary, Winifred Noakes (née Patten), have offered a fresh perspective on the history and personalities of the magazine in the 1920s.

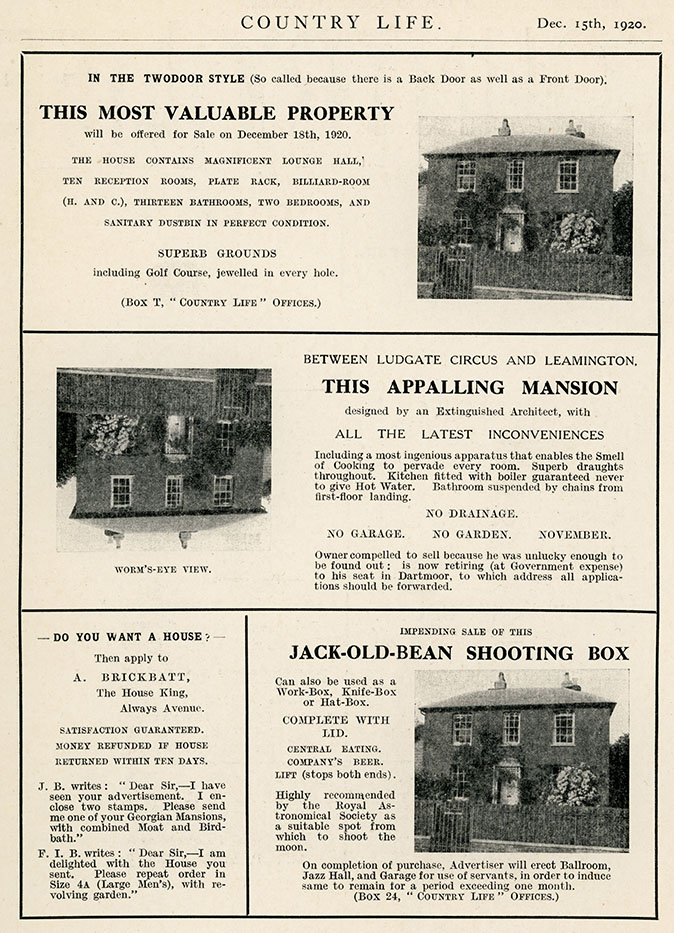

The bulk of the papers comprise ephemeral publications relating to social events that were produced on the magazine’s presses: invitations, tickets, menus and mock publications that satirised office life. All of them are of an extremely high quality, as you might expect given the labour and expertise inherent in producing a magazine every week.

The social round comprised then – as it still does now – a summer outing and a Christmas party. In the 1920s, the latter always fell on a Wednesday and at the fashionable Holborn Restaurant, Kingsway, demolished in 1955.

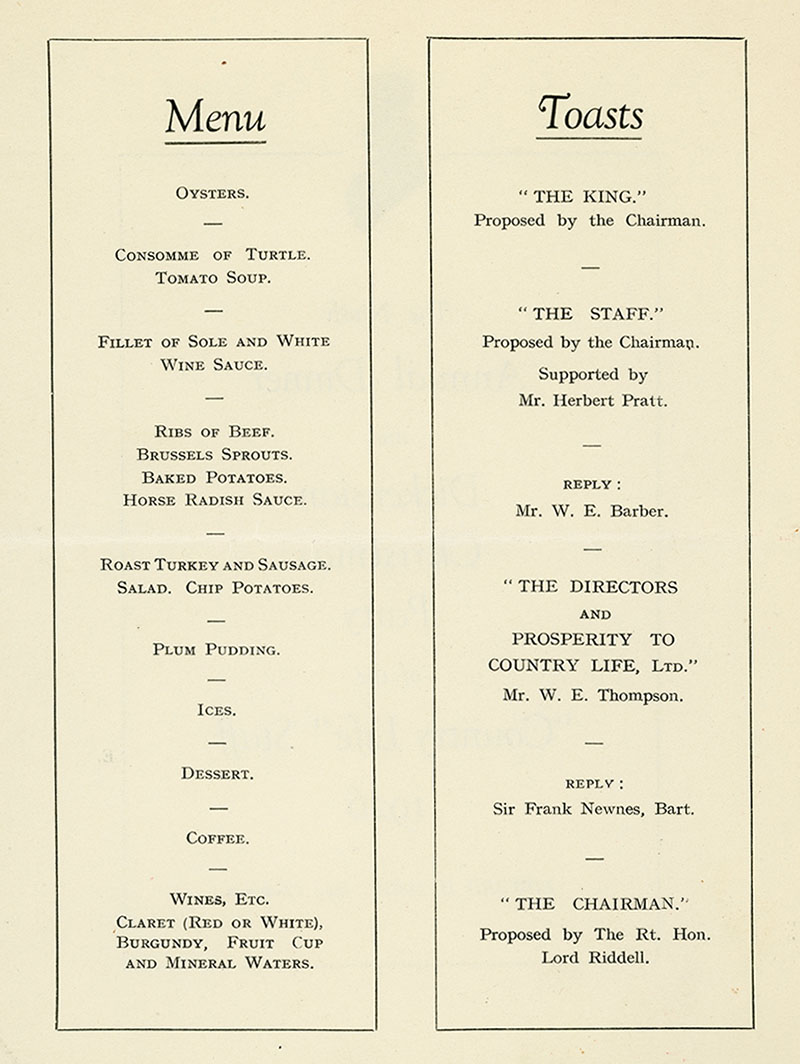

Representative of those parties is the earliest surviving programme and menu card, dated December 15, 1920. It takes the form of a mock, miniature issue of the magazine entitled ‘The staff’s extraordinary number’. On the front was a dinner menu of eight courses (opening, somewhat unbelievably, with turtle consommé, and accompanied by a selection of wines), as well as a toast list – to the King, the staff, the directors, the prosperity of Country Life and, finally, the chairman.

This essential format would remain unchanged at the heart of the Christmas celebrations for the remainder of the decade.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The scale of the dinner is uncertain, but it was clearly a splendid affair. Surviving invitation cards for later years show that Harden variously sat at tables numbered between 50 and 102, so there must have been numerous guests. Miss Patten’s 1923 menu card bears the signatures of 78 members of staff, all of whom presumably attended the meal. This is one of the few indications we have of the staff numbers in the period.

The dress code was – and always remained – morning dress (although, in 1926 and 1927, fancy dress was also permitted). Within the 1920 booklet are absurd advertisements, a Frontispiece photograph of a prize bull and a very arch description of the magazine’s office in Covent Garden, in the form of an architectural article. This incorporates some of the only known photographs of the interior as a working building, including the office of the founding director Edward Hudson, described as ‘The Eyrie of Literature’, and the typesetting room, ‘the chapel’.

At the back was a programme of entertainment, including popular songs performed by members of staff and two sketches. To help the audience, the relevant items on the programme are clearly labelled ‘humorous’.

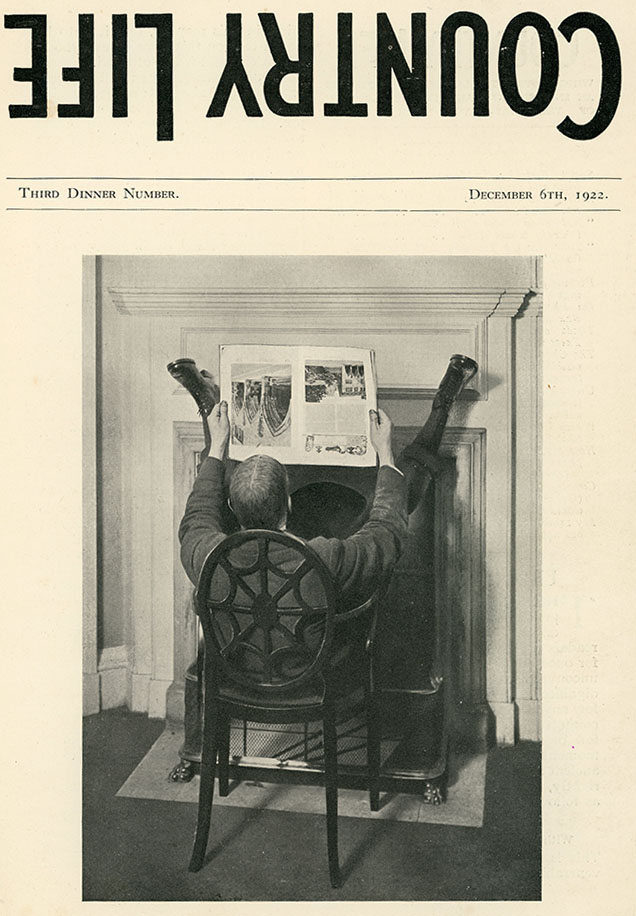

Two years later, in 1922, the magazine celebrated its 25th anniversary and the Christmas party grew more elaborate. Invitations were separately offered for the staff dinner at 6pm and the staff concert at 8pm for 8.15pm. The menu card (possibly distributed with a serious pamphlet history of the magazine called Leaves from the Family Tree in Covent Garden) took the form of a ‘topsy-turvy’ number of Country Life, with another satirical account of the office, this time illustrated with cartoon drawings.

The back cover gave the details of a new play about the magazine written by Christopher Hussey, then a young architectural writer who had joined the magazine fresh from Oxford in 1920. Two typescripts of Hussey’s play The Dummies (a punning reference to a stage in the magazine’s production process) or A Happy Family were preserved in Harden’s papers. He must have acted in the chorus, but Miss Patten played the lead female role, Lady Angelica Chippendale.

This ambitious production spurred the staff on to even greater efforts the following year, with a pantomime drama Printerella, again by Hussey. Only the text of the second two acts survive in Harden’s papers and the plot, an inverted version of the Cinderella story involving a cast of eastern and western journalists that certainly wouldn’t pass the censor today, is hard fully to reconstruct.

With them survive photos of the production; Harden was one of the chorus of husbands to Lilac, proprietress of the news-paper, the Great Chan of Tartary. The dinner itself celebrated the publication of the miniature edition of Country Life for the Queen’s Dolls House in Windsor. A copy was inserted into each menu card.

Printerella probably proved to be the high-water mark of Country Life’s Christmas entertainments. The following year, there was a medley performance called The Arcadian Review, a multi-authored production, structured around the form of the magazine, with sections entitled ‘frontispiece’, ‘leader’ and ‘correspondence page’.

More typical of the late 1920s, however, was the ‘Harvest Home’ of Christmas 1925, a programme of music and songs with one comic interlude called ‘The bathroom door’ set ‘early in the morning’ in ‘a large seaside hotel’. It’s not hard to imagine the theme of its humour or the quick-fire exchanges of a ‘Telephone misunderstanding’ performed by an all-male cast of four ‘office imps’ for Christmas 1930.

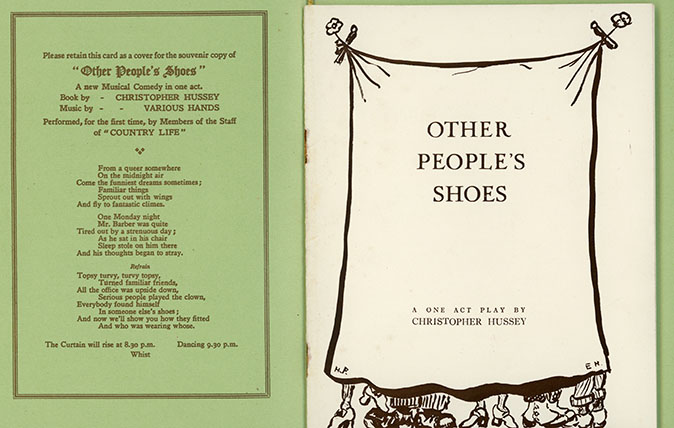

Two further plays are recorded: a ‘Mummers’ Play’ in 1926, the text (now lost) supposedly passed down in the oral tradition from the depths of time, and a one-act ‘musical comedy’, again by Hussey, in 1929, called Other People’s Shoes.

The conceit of this was that everyone in the office exchanged roles during a reform of the magazine (which proves to be a dream). Harden assumed the role of the managing editor for the performance and Miss Patten that of the fashion editor. The short text was printed in the menu card, perhaps evidence that it was to be read rather than acted entirely from memory.

If the performances grew less ambitious, however, the menu cards continued as elaborate as ever. In 1928, for example, the menu included a description of the party as a medieval feast illustrated with line drawings after the Luttrell Psalter and, in 1930, a spoof history of the magazine was illustrated with photographs of senior members of staff montaged into celebrated historic portraits. Cards, dancing and even soothsaying joined the entertainments. The 1930 menu card is the last to survive and this small but engaging window into the human life of the magazine closes.

It would be fascinating if any readers could provide more details – written or oral – about the extra-curricular activities of Country Life in the 20th century.

Credit: Paul Barker / Country Life Picture Library

What's changed in 120 years of Country Life? Everything and nothing

Clive Aslet has been connected with Country Life for all of his working life. Here, he explains how the magazine

Credit: Country Life

How Country Life’s 125-year journey began, thanks to a visionary founder

As Country Life celebrates its 125th anniversary, Michael Hall tells the remarkable story of how the magazine came into being

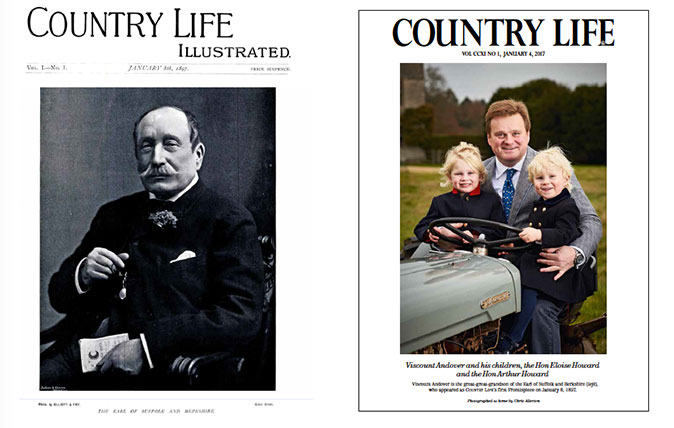

Credit: Country Life - 1897 to 2017

120 years on, how Country Life has continued in a changing world

We look back at the things which have changed in the 120 years since Country Life was first published.

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.