The man who made Glasgow: Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928)

The legacy of Scotland’s best-loved designer transcends the tragedies of his life and greatest work, says Charlotte Rostek.

Breaking out almost exactly four years later to the day, last month’s devastating second fire at Glasgow’s famous School of Art has spectacularly marred this 150th anniversary year of the designer and architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh. The public outpouring of grief on both occasions was and is profound and testifies to the real sense of loss that is felt in relation to one of Glasgow’s most iconic buildings and flagship educational institutions.

The silence, instead of the customary inner-city buzz, that now surrounds the site at Garnethill is disturbing. People stop at the edge of the cordon to view the shell – while it still stands – and move on. It is an exhibition of an unscheduled and unwelcome sort, which seems to mock the increasingly dynamic rehabilitation of Mackintosh and his legacy in his home city.

The contrast on entering another beloved Glasgow institution, Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, could not be greater. Here is the city’s centrepiece for the celebratory year and the most ambitious Mackintosh-themed exhibition for more than 20 years.

More than 250 objects, some rarely or never seen in public before, have been organised thematically and chronologically to explore Mackintosh’s creativity in the context of his contemporaries and of Glasgow itself – that exciting, expanding, cosmopolitan city, the burgeoning industries of which fostered an entrepreneurial spirit and buoyant private and civic patronage. This stimulating environment, coupled with the visionary direction by ‘Fra’ Newbery, then Head of the Glasgow School of Art, provided fertile ground for a whole generation of talented young men and women articulating dynamic ideas and a new artistic language – notably that unique variant of Art Nouveau known as the Glasgow Style.

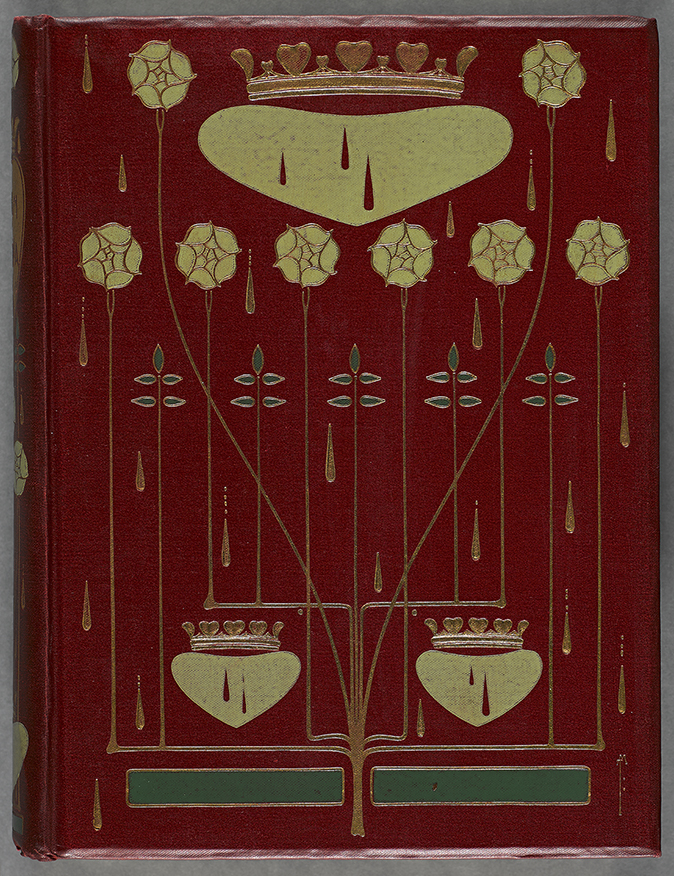

It comes as no surprise that the theme of art education sits at the centre of the exhibition. A rich array of objects illustrates the impressively diverse range of media in which students were able to receive rigorous training, allowing them to forge commercially successful careers: glass, ceramics, metalwork, furniture, needlecraft and embroidery, stained glass, bookbinding, mosaic, botanic drawing, interior design, to name a few. Among the artefacts are Mackintosh’s adorable watercolour Sea Pink; Talwin Morris’s influential designs for the publishers Blackie & Son; Jessie M. King’s book illustrations, which led to an international career; Ann MacBeth’s embroidered and appliqued The Sleeping Beauty; and Dorothy Carleton Smyth’s striking cover design for Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, one of the highlights in this section.

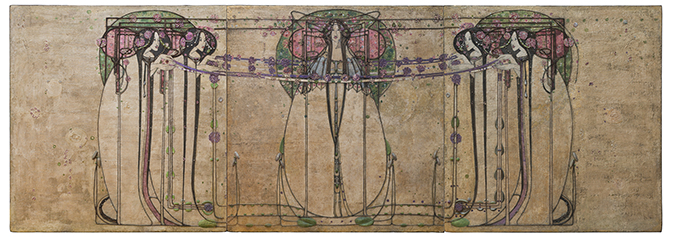

It’s not just beautiful, finished objects, but also the act of making itself that is explored in this exhibition. Pencil lines on Margaret Gilmour’s unfinished repoussé tray reveal the process of working metal, but it’s Margaret MacDonald’s magnificent May Queen that brings us most tantalisingly close. One of a pair made for the Ladies’ Luncheon Room in Glasgow’s Ingram Street Tearooms, the 15ft panel was originally installed well above head height; now we can see at eye level its twine and beads, loosely woven canvas, gesso and paint – even Margaret’s fingerprints preserved in some of the plaster.

The exhibition takes Mackintosh gently away from the commonly held perception of the isolated genius and weaves him into a rich and colourful tapestry of contemporary work. It hints at the relationships, the creative dialogue with fellow artists and companions, that forged stylistic similarities. However, it also highlights remarkable divergences. Mackintosh stands out. His was a more radical and innovative talent. The ‘shocking’ early poster designs of the ‘Spook School’; the deceptively simple adaptation of the square as a central motif for his groundbreaking furniture designs from about 1904; his architectural masterpieces The Hill House and the west wing of the Glasgow School of Art (here presented in film) – all reveal his departure from the mainstream.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Yet, after the achievements of his early career, Mackintosh’s work became unfashionable and his reputation faded. Disillusioned, he left Glasgow in 1914, never to return, and died in London 14 years later, aged just 60. Some of his contemporaries also followed their successes with early death, obscurity or worse, and quiet off-shoots from the main flow of the exhibition include a room devoted to the extraordinary architectural schemes of James Salmon Jr (1874–1924) and an almost sacral presentation of the exquisite Four Seasons by the Macdonald sisters, Frances (said to have killed herself) and Margaret, Mackintosh’s wife.

Hermann Muthesius, the German architectural writer, wrote in 1902 that ‘those who want to see art should bypass London and go straight to Glasgow’. Certainly this fulsome exhibition shows that the city’s richly artistic, progressive climate produced an astonishing legacy. It is a tragedy that one of its greatest buildings has now been lost, but the ideas that made the building great survive. And the esteem in which its architect is held makes us dare to hope that the School of Art will soon be rebuilt as the physical embodiment of those transforming ideas.

‘Charles Rennie Mackintosh Making the Glasgow Style’ is at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Argyle Street, Glasgow, until August 14 (0141 276 9599; https://www.glasgowlife.org.uk/museums/venues/kelvingrove-art-gallery-and-museum).

Charlotte Rostek is a Trustee of the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society, Curator Emerita for Dumfries House and consultant to Scottish Auctioneers Lyon & Turnbull.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

'That’s the real recipe for creating emotion': Birley Bakery's Vincent Zanardi's consuming passions

'That’s the real recipe for creating emotion': Birley Bakery's Vincent Zanardi's consuming passionsVincent Zanardi reveals the present from his grandfather that he'd never sell and his most memorable meal.

By Rosie Paterson

-

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabinQatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin has been setting the standard for Business Class travel since it was introduced in 2017.

By Rosie Paterson