The eloquence of line: Raphael’s drawings at the Ashmolean Museum

Caroline Bugler admires the beauty and expressive power of Raphael’s drawings.

Raphael (1483–1520) was a golden boy, blessed with a superabundance of talent, energy, charm and good looks. Although he died when he was only 37, he managed to squeeze an astonish ing amount of work into a brief career that started when he was barely in his teens, while he was living in his native Urbino.

He was only 25 when summoned to Rome by Pope Julius II in 1508, yet he had already carried out important artistic projects in the central Italian cities of Città di Castello, Perugia, Siena and Florence and made the acquaintance of the leading Italian artists of the time, including Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci.

The papal Court was a hotbed of artistic rivalry and intrigue—the famously curmudgeonly Michelangelo, who was at work on the Sistine Chapel, certainly felt threatened by the brill ant newcomer—but Raphael managed to navigate his way through the artistic politics and was given the prestigious task of decorating the Pope’s private rooms in the Vatican Palace.

The virtuosity of Raphael’s frescoes and oil paintings is evident at first glance, but the drawings offer a more intimate insight into his creative process as well as evidence of his extraordinary skill with pen, stylus and chalk. Some 120 of them are on show in this exhibition: 50 come from the Ashmolean’s own holdings and they’re supplemented by rarely seen examples from international collections, including the Albertina in Vienna and the Uffizi in Florence.

Raphael used drawing for a variety of purposes: to explore initial thoughts; to observe figures from life; to work out and modify poses and gestures before committing them to paint; to discover the expressive potential of the different media of charcoal, chalk, ink and metalpoint; to resolve entire compositions; and as the means of communicating his intentions to an army of assistants.

He also sometimes sent drawings as gifts to influential patrons and connoisseurs as friendly proof of his mastery. He gave one of them—a study of nude men—to Dürer and the German artist annotated it with an inscription stating that Raphael made it ‘to display his hand’. A vivid example of his dexterity, it shows the same bearded model in different poses, the red chalk applied with a harder touch for the sharply defined contours and softer strokes for the finely modelled musculature.

All the drawings on show depict figures—bodies in their entirety or in part, faces, hands and drapery—and the way they move and interact. There is always more emphasis on gesture and pose than on the spatial construction and one of the most eloquent sheets clearly illustrates the detailed thought that Raphael gave to this rhetorical aspect of his art.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

A black-chalk study for two of the foreground figures in his Transfiguration altarpiece commissioned by Pope Clement VII, it shows the heads and hands of two Apostles, one young and one old, their contrasting express ions and gesticulations conveying their different reactions to the fact that they are unable to cure a possessed boy without Christ’s assistance.

That study is highly finished, but Raphael was equally cap- able of quick notation, jotting down the essentials of a pose and trying out ideas and vari ations in a few quick strokes of the pen that look almost like doodles. In one of his sketches of a Madonna and Child, the lines exploring the shifting positions of the Christ Child’s legs loop restlessly to and fro, while the more static facial features are indicated in heavier, confident outlines.

The drawings also reveal the eclectic nature of Raphael’s inspiration and how he could draw upon a store of remembered images and blend them into something new. His study for the figure of Adam in the Disputà, a fresco in the Stanza della Segnatura, the Pope’s reception room in the Vatican, is a case in point. Its pose recalls Classical prototypes, such as the ancient Roman statue of the Spinario, a boy picking out a thorn in his foot, the Belvedere torso and the thrown-back head of the priest in the Hellenistic sculpture group Laocoön and the muscular body echoes Michelangelo’s nudes. Yet all these resonances are perfectly synthesised in a figure whose immediacy suggests it was drawn from a live model.

Exhibitions of drawings always demand concentrated looking on the part of the viewer, but this is not a dry academic show. The prime aim has been to present the drawings as experimental, inventive and dramatic works that can be enjoyed without any prior know ledge, rather than to painstakingly trace their exact relation- ship with the paintings. How ever, if you feel like comparing Raphael’s draughtsmanship with that of his contemporaries, the National Gallery’s ‘Michelangelo & Sebastiano’ exhibition, featuring several drawings by Raphael’s two arch rivals, is on until June 25. Shortly after it closes, the National Portrait Gallery’s ‘The Encounter: Drawings from Leonardo to Rembrandt’ opens on July 31 with an impressive array of portrait drawings.

‘Raphael: The Drawings’ is at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, from June 1 to September 3 (01865 278000; www.ashmolean.org)

Credit: The Art & Antiques Fair Olympia

Get free tickets to the The Art & Antiques Fair Olympia

Country Life readers are being offered free tickets for The Art & Antiques Fair Olympia.

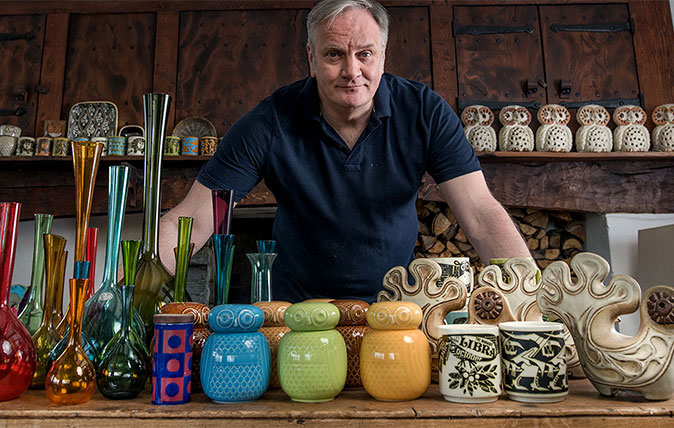

Why the British love eccentric collections – and what you need to know to start your own

The British are inveterate collectors of all sorts of items – Country Life's Anna Tyzack caught up with several of them.

How to move an art collection

Relocating can be stressful at the best of times. We reveal the art of moving art.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Kingswood School

Kingswood SchoolKingswood School is an independent, co-educational school in Bath where intellectual rigour, creativity, and compassion thrive.

By Country Life

-

Vintage tractors and memories of summers past, with Oliver Godfrey

Vintage tractors and memories of summers past, with Oliver GodfreyOliver Godfrey, head of machinery at Cheffins, joins the Country Life podcast to talk about the joys of vintage tractors

By James Fisher