From fighting for stockings to flying on the Moon: How nylon changed the world

Almost 90 years after it was first discovered, Martin Fone looks at the history of this mass produced man-made fibre.

On February 28, 1935, Wallace Carothers produced an example of the first wholly synthetic fabric, nylon 6.6, the culmination of eight years of research at the DuPont Experimental Station located on the banks of the Brandywine Creek in Wilmington, Delaware. For decades it was to be found everywhere, even on the moon: a flag made of nylon was the first to be planted on its surface in 1969.

Nylon is formed by combining two carbon-based substances so that they create a solid at the point where they meet. When it is heated and pushed through tiny holes under pressure, thin fibres are formed. These are then quickly pulled away and cooled to produce filaments which, at the time, were stronger and more resistant to heat and water than any other previously developed man-made fibre.

How it came to get its name is a matter of some controversy. In form it was similar to another DuPont produced fabric, the semi-synthetic rayon. Some believe that the original name was intended to be 'No-Run', a reference to its durability, but was dropped because of concerns that it might become a hostage to fortune. The letters were reversed and then morphed through 'nilon' to 'nylon'.

Another theory is that it was derived from the hometowns of the principal scientists who worked on the project, New York and London, while others suggest that it was an acronym of 'Now You’ve Lost, Old Nippon', reflecting the emergence of a credible rival to silk. It may just be, though, that the suffix was an arbitrary selection to conform with the naming convention set by rayon.

What is clear is that the complex manufacturing process, coupled with a patent for the polymer obtained in September 1938, gave DuPont a considerable commercial opportunity that they were keen to exploit. The first commercially available product using nylon was Dr West’s Miracle-Tuft, a toothbrush with synthetic nylon bristles, launched by the Weco Products Company of Chicago. The advertising boasted that this brush without bristles was 'made possible by this triumph of modern chemistry', although in the copy the fibres were said to be made of 'Exton'.

The real cash cow, though, was to prove to be women’s hosiery. In the 1930s silk stockings were all the rage, but their cost meant that they remained a luxury item. The emergence of nylon as a viable alternative to silk meant that stockings could be manufactured more cheaply with the added bonus that they were more robust.

DuPont released four thousand unbranded pairs of nylon stockings to the public for the first time on October 24, 1939. Costing between $1.15 and $1.35 a pair, depending on their sheer, they proved an instant hit, the six shops in Wilmington that were stocking them selling out by 1pm. The New York Times reported that 'customers were lined three deep at the counters', many of the men. When they were rolled out nationally on May 15, 1940, four million pairs had been sold within the first two days.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The availability of nylon stockings, though, came to an abrupt halt when the United States entered the Second World War and DuPont switched production of nylon from stockings to parachutes and other forms of military equipment. Some women resorted to painting their legs while others sourced their stockings from the black market, where a pair could cost up to $20. Inevitably, such a valuable commodity became a target for criminals: one family in Louisiana was robbed of 18 pairs, and the police in Chicago ruled out robbery as a motive for a murder because the nylons were untouched.

The desire for the return of nylon stocking was encapsulated in George Marion Jnr’s song, When Nylons Bloom Again (1943), the lyrics of which included the lines 'I’ll be happy when the nylons bloom again/ Cotton is monotonous to men/ only way to keep affection fresh/ get some mesh for your flesh'. Eight days after Japan’s surrender in August 1945, they got their wish.

DuPont announced that it was resuming production. Its PR department went into overdrive, claiming that it would be able to produce 360 million pairs in a year, a target that its production department was not geared up to meet. When pent-up demand met the cold reality of low stock numbers, trouble was bound to follow.

As supplies of the stockings reached the stores, queues would start forming, 40,000 appearing outside a store in Pittsburgh which had just 13,000 pairs to sell. In New York queues of some 30,000 women were reported. When the stockings sold out, the disappointed women reacted furiously, a paper in Atlanta, Georgia, running the headline 'Women Risk Life and Limb in Bitter Battle for Nylons'. Countless reports appeared up and down the United States of women fighting with each other and pulling hair to get their hands on a pair of nylons. Shelves and displays went flying in the turmoil.

It was not until March 1946 that DuPont reached production levels that met demand and the riots were quelled. The civil disorder marked the beginning of the end of DuPont’s cosy monopoly. The company, rather patronisingly, rebutted accusations that they had delayed production to increase demand and maximise profits by claiming that women had too much time on their hands and nothing better to do than queue and hoard. In 1951, threatened with an anti-trust suit, DuPont agreed to share the nylon licence with the Chemstrand Corporation and then, eventually, with others.

Nylon proved revolutionary in other ways. Its use in the manufacture of lightweight luggage ushered in the age of carry-on baggage on aircraft, while, in combination with the tufting method of construction, nylon brought the cost of carpeting to a level that most household budgets could afford.

Dubbed as the 'Year of the blending of fibres' by the Textile Recorder, 1951 saw the emergence of blended fabrics, nylon often paired with wool or polyester, or spandex. While remaining cheap and retaining the properties of nylon, they eliminated some of the problems that had previously emerged, making the fabrics more breathable, less prone to unravelling, and less likely to store a static charge that gave a nasty surprise to the unwary.

The lure of nylon, though, began to wane from the 1970s when environmental concerns took centre stage. Its strength and durability made it difficult to dispose of, taking between thirty to 40 years to degrade, while incineration released toxic fumes and ash containing hydrogen cyanide. The manufacturing process was energy-intensive, used enormous quantities of water, and produced as a by product nitric oxide, a greenhouse gas that is 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Washing nylon fabrics introduced microplastics into the water system and discarded nylon products were increasingly seen as endangering wildlife.

Manufacturers responded to these concerns by reducing the amount of nylon in their products or by finding substitutes. Nevertheless, the global market for nylon was still valued at $31.09 billion in 2023.

As for Wallace Carothers, he never saw the success of the product he had worked so hard to develop. A depressive, he swallowed a lethal cocktail of lemon juice and potassium cyanide on April 28, 1937. While his death was widely reported in the United States at the time, his fame did not possess the durability of nylon and he quickly slipped into obscurity.

Surely, the 90th anniversary is a time to remember his contribution, producing a material that was truly revolutionary in its day.

Martin Fone is the author of 'Fifty Curious Questions: Pabulum for the Enquiring Mind'

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

Bye bye hamper, hello hot sauce: Fortnum & Mason return to their roots with a new collection of ingredients and cookware

Bye bye hamper, hello hot sauce: Fortnum & Mason return to their roots with a new collection of ingredients and cookwareWith products sourced from around the world, the department store's new ingredients and cookware collection is making something of a splash.

-

A seven bedroom Buckinghamshire rectory that might be a little haunted

A seven bedroom Buckinghamshire rectory that might be a little hauntedGrade II-listed the Old Rectory is a home of astounding charm and beauty, and comes with a friendly visitor.

-

Curious Questions: Why do woolly hats have bobbles?

Curious Questions: Why do woolly hats have bobbles?Some can rock a bobble hat, others will always resemble Where’s Wally, but the big question is why the bobbles are there in the first place. Harry Pearson finds out as he celebrates a knitted that creation belongs on every hat rack.

-

Curious Questions: We used to fly cars across the English Channel in 20 minutes — why did we stop?

Curious Questions: We used to fly cars across the English Channel in 20 minutes — why did we stop?It seems hard to believe, but taking your car across the English Channel to France by air actually pre-dates the cross-channel car ferry. So how did it fall out of use almost 50 years ago? Martin Fone investigates.

-

Curious Questions: Who invented the rear-view mirror?

Curious Questions: Who invented the rear-view mirror?Although obvious now, the rearview mirror wasn't really invented until the 1920s. Even then, it was mostly used for driving fast and avoiding the police.

-

Curious Question: Did the limerick originate in Limerick?

Curious Question: Did the limerick originate in Limerick?Before workers wasted time scrolling Twitter or Instagram, they wasted their time writing limericks.

-

You rang, your majesty? What it was like to be a servant in the Royal Household

You rang, your majesty? What it was like to be a servant in the Royal HouseholdTending the royal bottom might be considered one of the worst jobs in history, but a life in elite domestic service offered many opportunities for self-advancement, finds Susan Jenkins.

-

Curious Questions: Why are there so few smiles in art?

Curious Questions: Why are there so few smiles in art?Centuries of portraits down the ages — and vanishingly few in which the subjects smile. Carla Passino delves into the reasons why, and discovers some fascinating answers.

-

Tanks, tulips and taxidermy: The strange lives of Britain's most eccentric collectors

Tanks, tulips and taxidermy: The strange lives of Britain's most eccentric collectorsFive collectors of unusual things, from taxidermy to tanks, tulips to teddies, explain their passions to Country Life. Interviews by Agnes Stamp, Tiffany Daneff, Kate Green and Octavia Pollock. Photographs by Millie Pilkington, Mark Williamson and Richard Cannon.

-

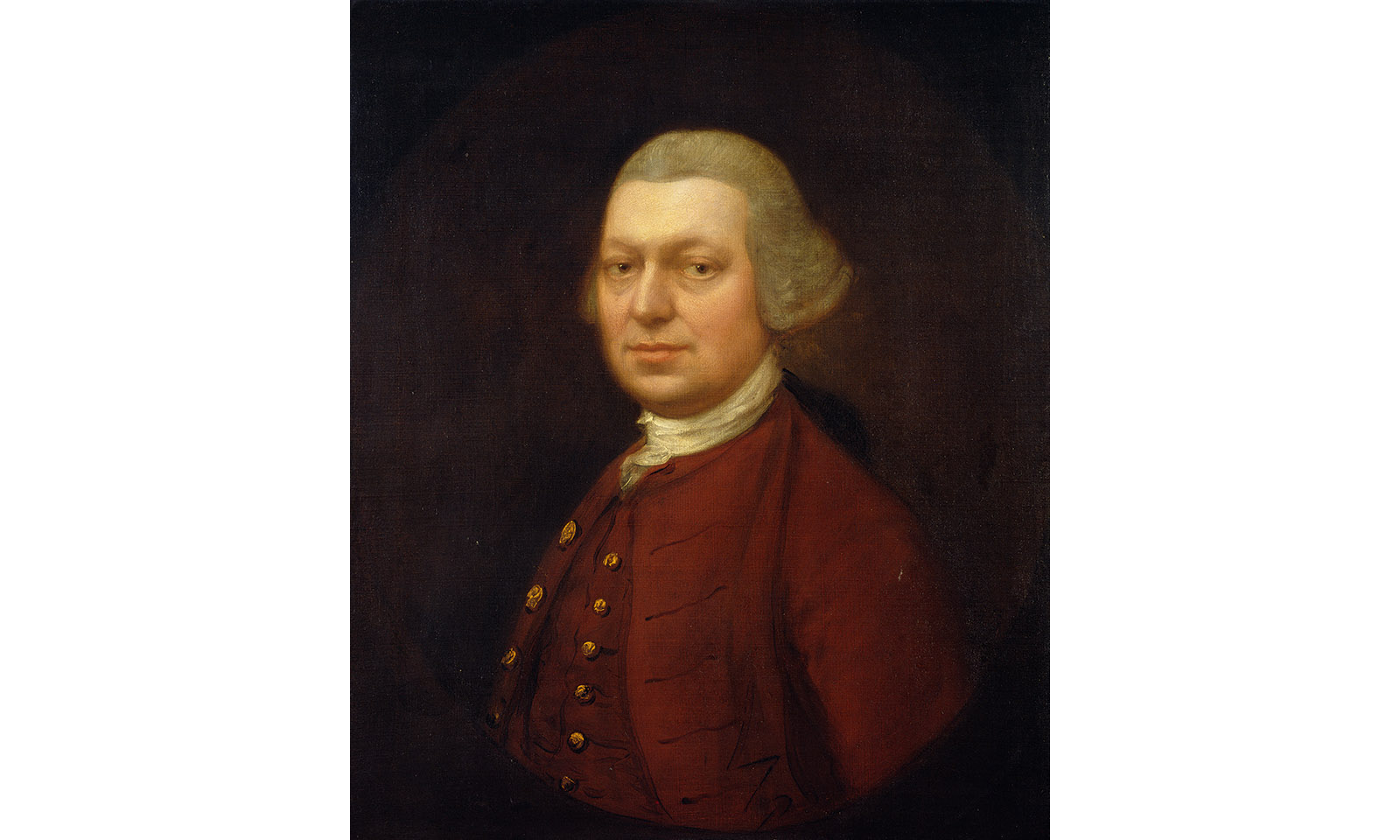

One of the cleverest pictures ever made, and how it was inspired by one of the cleverest art books ever written

One of the cleverest pictures ever made, and how it was inspired by one of the cleverest art books ever writtenThe rules of perspective in art were poorly understood until an 18th century draughtsman made them simple. Carla Passino tells the story of Joshua Kirby.