Curious Questions: Why do woolly hats have bobbles?

Some can rock a bobble hat, others will always resemble Where’s Wally, but the big question is why the bobbles are there in the first place. Harry Pearson finds out as he celebrates a knitted that creation belongs on every hat rack.

Jens Martin Knudsen is known to football fans around the world as the goalkeeper of the tiny Faroe Islands when the team pulled off one of international football’s greatest acts of giant-killing, defeating Austria 1–0 in the 1990 European Championships. It wasn’t the goalie’s string of brilliant saves that attracted the world’s attention, however, but rather what he was wearing on his head: a knitted woollen hat. Mr Knudsen has gone down in sporting folklore as ‘the bobble-hat ’keeper’. That hat, homespun and a little goofy, epitomised the romance of the sporting underdog.

That one of the most celebrated modern exponents of the bobble hat should be a Scandinavian is fitting, as the first person we can confirm wearing one is Freyr, Viking god of peace and pleasure, as he appears on a little 11th-century statue unearthed in Sweden in 1904. Freyr’s hat is tall and the pompom is only the size of an acorn, but one imagines it kept the Norse god’s head warm when he was galloping alongside the fjords astride his pet boar, Gullinbursti.

https://youtu.be/AnbZHNS4O1k?si=Wg9OZbxvmCPm7gES

Wool hats such as the one Freyr is sporting were made using a technique called nålbinding, in which the threads are formed into a tube and then pulled shut at one end. To cover the gathered seam, an adornment was added — sometimes a tassel, but more often a small ball made from mixed offcuts of wool. The bobble hat was born of necessity.

In England and Wales, a simple knit hat much like the modern beanie (see box) became popular in the 16th century. Known as Monmouth caps after the town in which they’d been made since the 1300s, these ancestors of the bobble hat were given a massive sales boost in 1571, when Parliament passed laws making it compulsory for everyone over the age of six to wear a woollen hat on Sundays and holidays.

Mr Knudsen had started wearing his celebrated bobble hat after sustaining a head injury as a teenager and the protective properties of the pompom have long been recognised. The Monmouth cap became the preferred headgear of sailors and they soon added a pompom to the top, not so much for decoration as to stop them hurting their heads on the low ceilings and hatchways on board ship. The tradition of the sailors’ pompom was later transferred to naval berets. In the Netherlands, naval tradition has it that if you can touch a sailor’s pompom without him noticing, it’ll bring good luck. However, if you touch it and he does notice, you must give him a kiss — which may be lucky for some.

The pompom itself (from the Old French pombe, meaning a knot of ribbons) was and is an adornment for all sorts of hats, from Napoleonic infantrymen’s shakos to Roman Catholic clergymen’s birettas via the broad-brimmed hats of the Black Forest and the Scots’ tam o’ shanter. In some societies, the size and colour of the pompom might help identify the wearer, indicating their place in the hierarchy or marital status.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

From the Victorian era, the bobble hat lost ground to flat caps and trilbies, but it enjoyed an unexpected revival in the Swinging Sixties, thanks in part to Mike Nesmith of pop group The Monkees. Mr Nesmith had turned up to the audition for the hit US television show featuring the band wearing a green bobble hat and rarely took it off thereafter. His wife, Phyllis, later explained that the hat symbolised her husband’s decision ‘to be totally himself’. Eventually, the Texan guitarist would start to feel oppressed by his association with the bobble hat (in the original cast list, he was referred to simply as ‘Wool Hat’). After several years of stardom, he finally got rid of it by throwing it into the audience at a concert.

The famed Monkees hat had, however, set a trend among youngsters and it was picked up by football and rugby fans, who began wearing pompom hats in team colours. The bobble hat was given a further punch of panache in the 1960s by French skier Jean-Claude Killy, a man of such warm and twinkly Gallic charm that you suspected he could create an avalanche merely by smiling. It would appear almost impossible for a man to look cool and sexy in a bobble hat, although George Lazenby’s James Bond confidently wore one in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Yet, somehow, the triple Olympic champion managed it.

This woollen creation is a unisex garment, but, in the days when women favoured elaborate hairstyles, the thought of crushing their expensively assembled waves beneath one would have been unthinkable. The easier haircuts of the 1960s ushered in a more glamorous era for the headwear. The Princess Royal was an early adopter, setting a royal trend that has recently been revived by The Princess of Wales.

For men, the bobble hat’s fashion credibility was dented in the 1970s by Benny Hawkins in Crossroads, who paired his bobble hat with a vacant grin. Latterly, Ed Sheeran has done a Mr Nesmith-like job in placing it back on every chap’s hat rack — and he’s been joined by Harry Styles, David Beckham and Bradley Cooper. Mr Knudsen, meanwhile, continued to wear his bobble hat on the pitch until his retirement in 2007. You can still see his famous headgear, however, as it now hangs in the FIFA Museum in Zurich, Switzerland.

Challengers to the bobble hat’s throne

The chullo

The Andean cap with ear flaps and ties is said to have been inspired by the shape of the steel helmets worn by the Spanish conquistadors

The toque

In its native Canada, the spelling — toque, tuque or touque? — of this knitted cap that was worn by French trappers in the 18th century is often the subject of feverish debate

The beanie

This hat originated in the US in the 1900s, where it was worn by students, often in the colours of their college. The name comes from the slang word for head

The tophue

Scandinavia’s ‘top cap’ was inspired by the Phrygian cap worn by French revolutionaries. It is the preferred headgear of garden gnomes

The toboggan

In the US, bobble hats were often called toboggan hats because people wore them when sledging. However, in the southern states, where snow-covered ground is rare, the name — usually shortened to ‘boggin’ — has come to refer to the hat, not a sled

Harry Pearson is a journalist and author who has twice won the MCC/Cricket Society Book of the Year Prize and has been runner-up for both the William Hill Sports Book of the Year and Thomas Cook/Daily Telegraph Travel Book of the Year.

-

Sanderson's new collection is inspired by The King's pride and joy — his Gloucestershire garden

Sanderson's new collection is inspired by The King's pride and joy — his Gloucestershire gardenDesigners from Sanderson have immersed themselves in The King's garden at Highgrove to create a new collection of fabric and wallpaper which celebrates his long-standing dedication to Nature and biodiversity.

By Arabella Youens

-

The coveted Hermès Birkin bag is a safer investment than gold — and several rare editions are being auctioned off by Christie’s

The coveted Hermès Birkin bag is a safer investment than gold — and several rare editions are being auctioned off by Christie’sThere are only 200,000 Birkin bags in circulation which has helped push prices of second-hand ones up.

By Lotte Brundle

-

From fighting for stockings to flying on the Moon: How nylon changed the world

From fighting for stockings to flying on the Moon: How nylon changed the worldAlmost 90 years after it was first discovered, Martin Fone looks at the history of this mass produced man-made fibre.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: We used to fly cars across the English Channel in 20 minutes — why did we stop?

Curious Questions: We used to fly cars across the English Channel in 20 minutes — why did we stop?It seems hard to believe, but taking your car across the English Channel to France by air actually pre-dates the cross-channel car ferry. So how did it fall out of use almost 50 years ago? Martin Fone investigates.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Who invented the rear-view mirror?

Curious Questions: Who invented the rear-view mirror?Although obvious now, the rearview mirror wasn't really invented until the 1920s. Even then, it was mostly used for driving fast and avoiding the police.

By Martin Fone

-

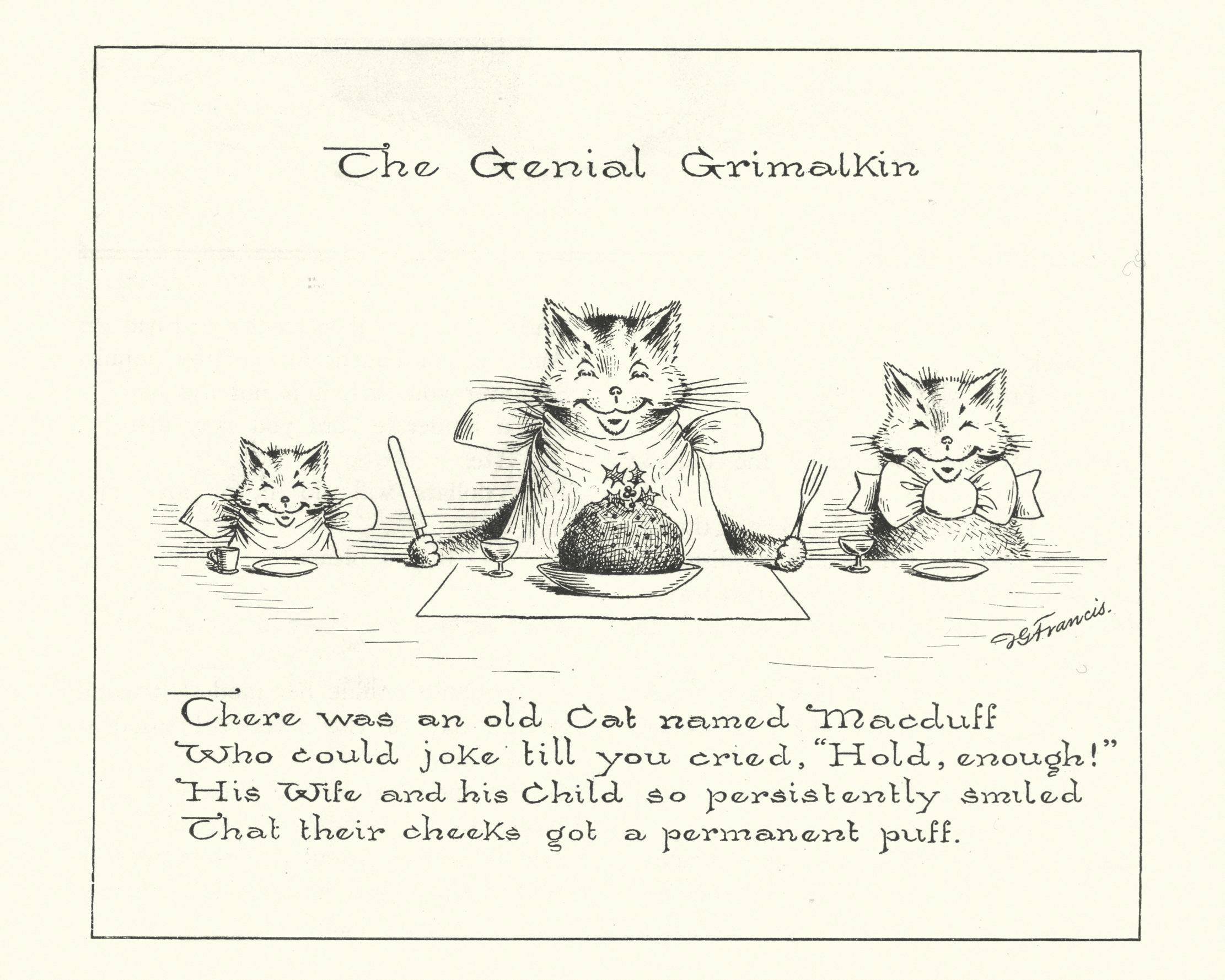

Curious Question: Did the limerick originate in Limerick?

Curious Question: Did the limerick originate in Limerick?Before workers wasted time scrolling Twitter or Instagram, they wasted their time writing limericks.

By Martin Fone

-

You rang, your majesty? What it was like to be a servant in the Royal Household

You rang, your majesty? What it was like to be a servant in the Royal HouseholdTending the royal bottom might be considered one of the worst jobs in history, but a life in elite domestic service offered many opportunities for self-advancement, finds Susan Jenkins.

By Country Life

-

Curious Questions: Why are there so few smiles in art?

Curious Questions: Why are there so few smiles in art?Centuries of portraits down the ages — and vanishingly few in which the subjects smile. Carla Passino delves into the reasons why, and discovers some fascinating answers.

By Carla Passino

-

Tanks, tulips and taxidermy: The strange lives of Britain's most eccentric collectors

Tanks, tulips and taxidermy: The strange lives of Britain's most eccentric collectorsFive collectors of unusual things, from taxidermy to tanks, tulips to teddies, explain their passions to Country Life. Interviews by Agnes Stamp, Tiffany Daneff, Kate Green and Octavia Pollock. Photographs by Millie Pilkington, Mark Williamson and Richard Cannon.

By Agnes Stamp

-

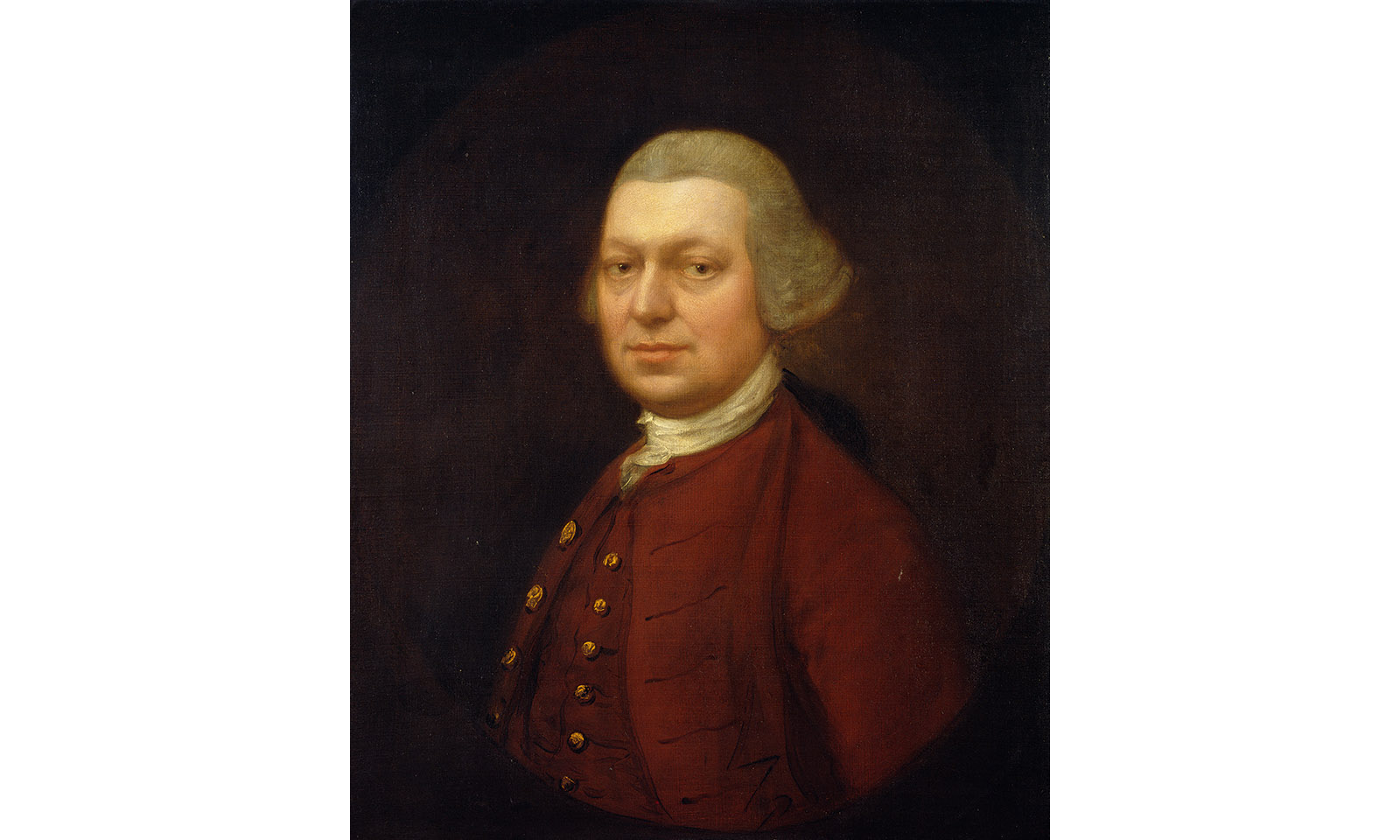

One of the cleverest pictures ever made, and how it was inspired by one of the cleverest art books ever written

One of the cleverest pictures ever made, and how it was inspired by one of the cleverest art books ever writtenThe rules of perspective in art were poorly understood until an 18th century draughtsman made them simple. Carla Passino tells the story of Joshua Kirby.

By Carla Passino