The Scottish artists who mashed up Dali and Boticelli to make their mark in the 20th century

Duncan MacMillan applauds an exhibition that reassesses the contribution made by Scottish artists to the great movements of Modern art.

In 1950, there was public outrage when a big abstract painting by William Gear called Autumn Landscape was bought by the Arts Council. Gear was a Scot. A ‘monument man’, who, to their enduring gratitude, cared for living German artists as well as for those of the past, he had gone straight from Germany to Paris in 1947. William Turnbull, Eduardo Paolozzi and, more briefly, Alan Davie were also in Paris. There, they developed a savage, new, abstract and expressive version of Modernism: art for a new world that was not an easy one.

It was no coincidence that it was Scots who led the way in reconnecting with Europe after the war. There was a long-standing involvement of Scottish artists with Europe and with new artistic ideas, and this exhibition sets out to explore it.

Gear’s painting is in the show, together with dramatic works by Davie, although it’s a pity that Paolozzi and Turn-bull are less well represented. Otherwise almost forgotten, Charles Pulsford’s Three Angels (1949 shows that he, too, shared their radical approach. Together, the work of these artists challenges the view that, as radical ideas cascaded down from Europe, our own artists could only play catch-up. This group was stimulated by the international mix of artists in Paris, but their art was their own.

Right at the beginning of the century, too, at least one Scottish artist, the Colourist J. D. Fergusson, was not waiting humbly for enlightenment, but was fully part of the excitement in Paris between 1907 and 1910. His big painting At My Studio Window, a fragmented vision of a nude woman against an open window, dates from 1910. Contemporary with the first Cubist works of Braque and Picasso, it reflects similar ideas, but is not dependent on their example.

After the war, Fergusson again showed his originality with semi-abstract paintings of naval dockyards. William McCance’s take on machines and machinery – notably in his remarkable drawing, Machine Head – owes something to Fergusson and to Futurism and Vorticism, too. It is, nevertheless, highly individual. Beatrice Huntington was also in Paris before the war and her Muleteer from Andalucia shows her completely at ease with the new Cubist idiom.

Sculpture is an especial delight in this show. Fergusson and McCance both made remarkable sculptures, but Tom Whalen and Norman Forrest’s works are a revelation. Forrest’s near abstract Figure in Walnut (Nude) from 1934 is exquisite, an individual and completely self-confident rendering of what was by now the prevailing Modernist idiom. Merlyn Evans’s Cyclops in polished black stone is a startling essay in pure abstraction.

Begun in 1929, William Johnstone’s big painting A Point in Time – a swirling, abstract landscape of the artist’s native Borders, notionally extended in time as well as in space – is a masterpiece of the period. It also pre-dates by some years Henry Moore’s use of similar landscape forms.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

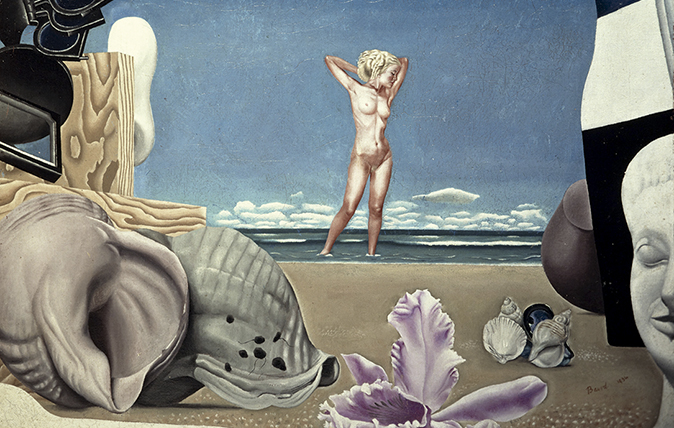

Johnstone encountered Surrealism as a student in Paris. Edward Baird did not enjoy such close contact, but nevertheless produced several outstanding paintings inspired by Surrealist ideas, such as Distressed Area (1936–38). Alexander Allan is one of several artists brought to light by this show and his Fantastic Landscape (about 1939) is an equally successful Surrealist essay. Margaret Mellis and Wilhelmina Barns-Graham both went from Edinburgh to St Ives to become part of the distinctive take on Modernism that blossomed there.

Fergusson features again in this story, promoting Modern art in Glasgow during the Second World War. Emigré artists Jankel Adler and Josef Herman were also part of the flourishing new Modernism in the city and helped to shape the radical painting of Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde.

Not everybody was as successful in absorbing new ideas and generating new forms from them. William Gillies and John Maxwell, for instance, both responded in a rather clumsy way to the exhibition of 25 works by Paul Klee held in Edinburgh in 1934, although they did at least try. William McTaggart’s grand painting After the Storm, Loch Lomond (1931–2) is a much more successful response to a major Edvard Munch show held three years earlier.

These and other similar exhibitions from Sweden, Germany, Belgium and elsewhere, as well as from France, were promoted by the artists themselves. They demonstrated their energetic curiosity about other people’s art, wherever it was to be found.

The real test of the current exhibition, however, is whether the works could stand the comparison if it was not just a Scottish show, but sought instead to tell the whole story of Modernism. The answer must be, without apology, that a good many of them could, indeed, hold their own in any company.

‘A New Era: Scottish Modern Art 1900–1950’ is at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (Modern Two), 75, Belford Road, Edinburgh, until June 10 (0131–624 6200; www.nationalgalleries.org)

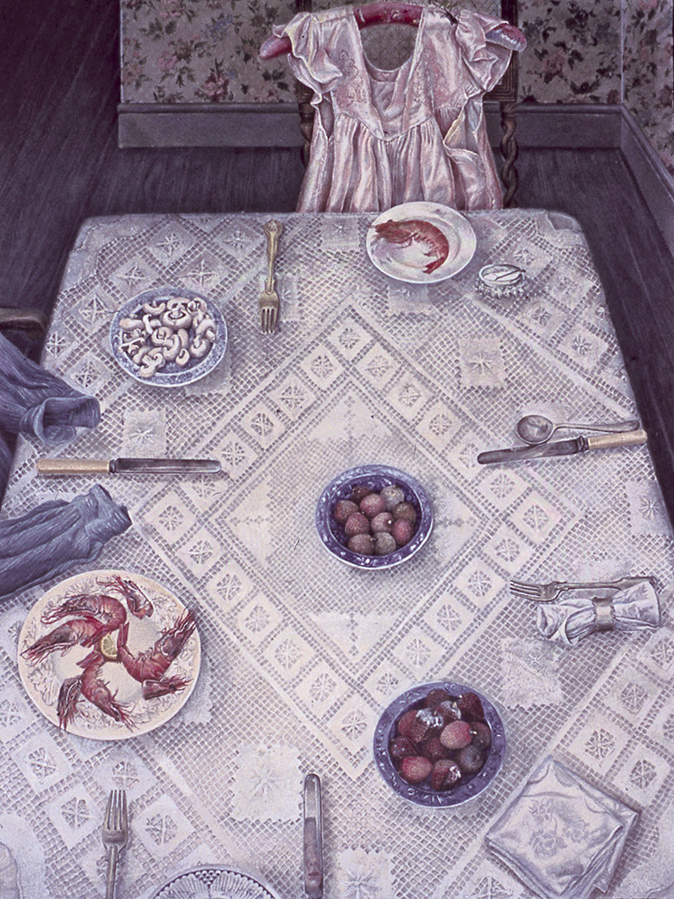

My favourite painting: Prue Leith

'I love this picture for its oddly surreal faces in the knives and empty clothes'

My Favourite Painting: Philip Trevelyan

Diamonds: A Jubilee Celebration at Buckingham Palace

A visit to Buckingham Palace reveals more than glittering diamonds

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)With more buyers looking at London than anywhere else, is the 'race for space' finally over?

By Annabel Dixon

-

Helicopters, fridges and Gianni Agnelli: How the humble Fiat Panda became a desirable design classic

Helicopters, fridges and Gianni Agnelli: How the humble Fiat Panda became a desirable design classicGianni Agnelli's Fiat Panda 4x4 Trekking is currently for sale with RM Sotheby's.

By Simon Mills