My favourite painting: Monty Don

'Rembrandt has captured human love at its most intimate and tender'

A Woman Bathing in a Stream, 1654, by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–69), 24¼in by 18½in, National Gallery, London

Monty Don says:

My grandfather took me to an art gallery every school holidays and, as my education progressed, we slowly worked our way through the London collections. Rembrandt, he told me, was the greatest artist who had ever lived. I nodded, but was uncertain on what to look for that would confirm that judgement. Then I saw this painting and instantly knew.

The subject – almost certainly Rembrandt’s common-law wife, Hendrickje Stoffels – is not especially beautiful nor has a body or demeanour that might command especial attention. But, as she lifts the hem of her shift to wade in the water, she is made transcendent by Rembrandt’s genius.

In this, the simplest of moments by an ordinary person in a painting that is hardly more than a sketch, Rembrandt has captured human love at its most intimate and tender. And there is no more worthy subject than that.

Monty Don is a writer, gardener and television presenter. His new book Paradise Gardens is out now, published by Two Roads.

John McEwen comments on A Woman Bathing in a Stream:

Rembrandt left this painting untitled. If it is a sketch for a biblical or mythological subject, it is unique in his work. He did not consider it a mere ‘sketch’: it is signed and dated.

Rembrandt’s wife, Saskia van Uylenburgh, his social superior, whom he wed in 1634, died in 1642. Of their children, only Titus, a baby at her death, survived. She and Rembrandt had made a joint will, but days before she died, she left everything to Titus. This meant the artist lost his entire estate. He was named his son’s guardian and the new will’s executor.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Geertje Dircx, Titus’s nursemaid, became Rembrandt’s mistress. Their time together was not happy, and when she manoeuvred to marry him, there began a saga of legal wrangles, rows and sibling betrayal that ended with her incarceration on his evidence for five years in a ‘house of correction’. He was supported by his new mistress, Hendrickje Stoffels (b.1626). Geertje was eventually released in 1655, but died soon after.

The year of this painting, 1654, Hendrickje was accused of ‘whoredom’ with Rembrandt. She pleaded guilty and was banished from her church. Three months later, she gave birth to the painter’s child, Cornelia.

Rembrandt never paid for his house, the origin of the financial problems that bedevilled the latter part of his life. To shield himself from creditors, he made Hendrickje and Titus form an art dealership, with himself as adviser receiving ring-fenced benefits. He dictated the terms, some of which played son and mistress against each other. In legal statements, Hendrickje called herself his wife. She died in 1663, leaving her effects to him and Cornelia.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producers

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producersStormzy, Rihanna and the Rolling Stones are just a part of the story at Osea Island, a dot on the map in the seas off Essex.

By Lotte Brundle

-

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The Season

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The SeasonHere's how to navigate this summer's top events in style, from those who know best.

By Madeleine Silver

-

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite painting

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite paintingAlexia Robinson, founder of Love British Food, chooses an Edwin Landseer classic.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

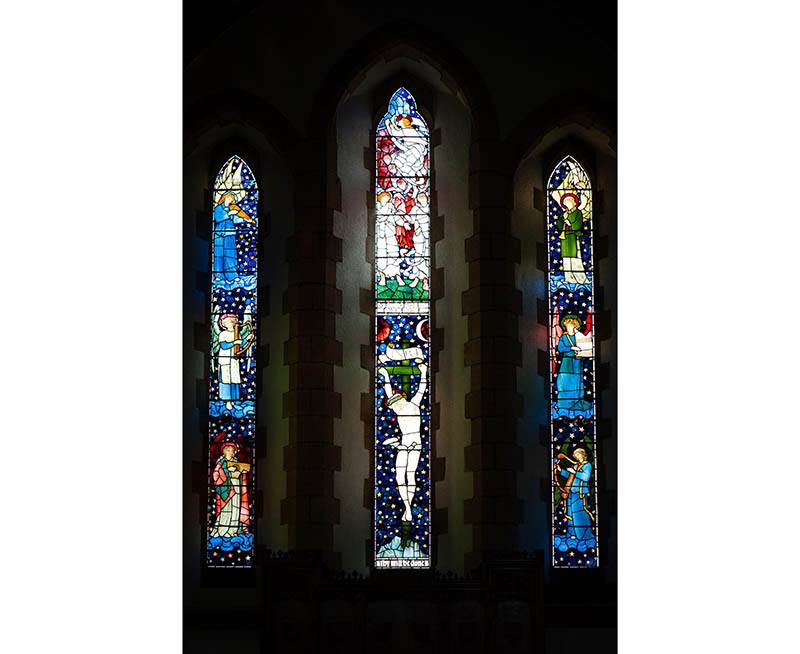

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in Britain

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in BritainThe painter Edward Burne-Jones turned from paint to glass for much of his career. James Hughes, director of the Victorian Society, chooses a glass masterpiece by Burne-Jones as his favourite 'painting'.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subject

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subjectFor Country Life's My Favourite Painting slot, the writer Emily Howes chooses a work by a daring and challenging artist: Frank Auerbach.

By Toby Keel

-

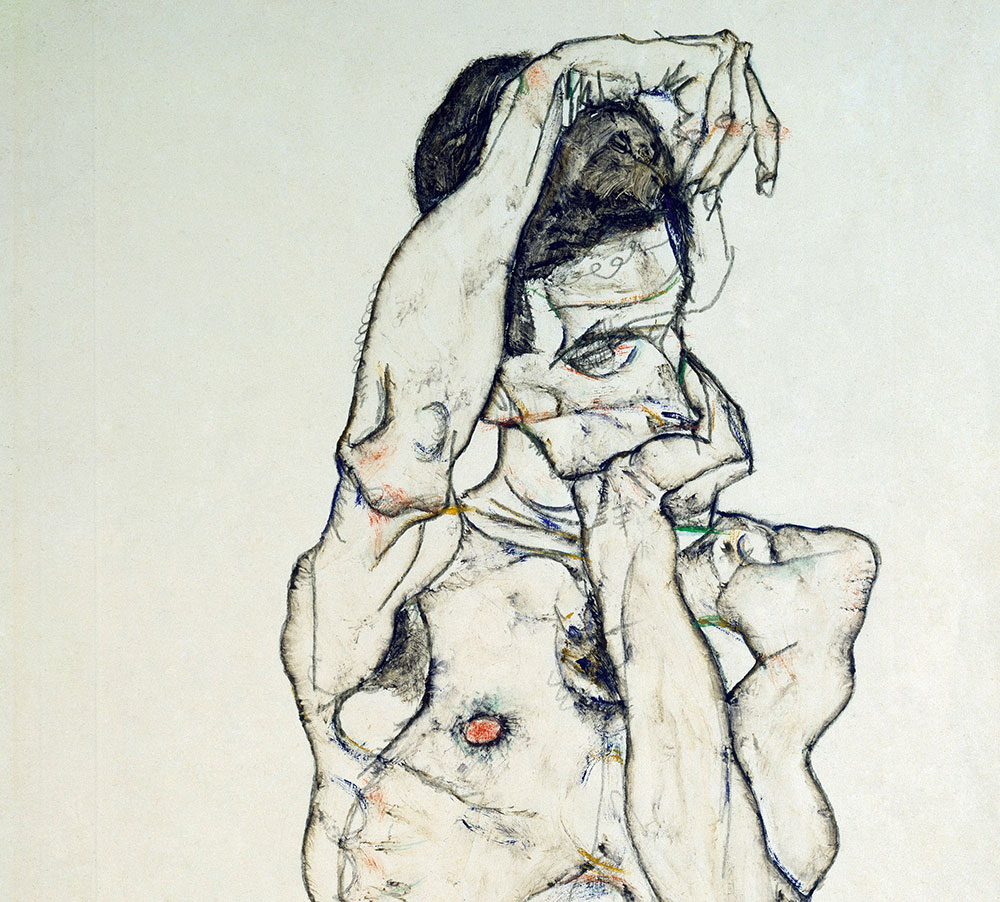

My Favourite Painting: Rob Houchen

My Favourite Painting: Rob HouchenThe actor Rob Houchen chooses a bold and challenging Egon Schiele work.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson'That's why this is my favourite painting. Because it invites you to imagine'

By Charlotte Mullins

-

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shock

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shockAs the National Gallery turns 200, the chair of its board of trustees, John Booth, chooses his favourite painting.

By Toby Keel

-

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearing

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearingChristopher Price of the Rare Breed Survival Trust on the bucolic beauty of The Magic Apple Tree by Samuel Palmer, which he nominates as his favourite painting.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon'Lesson Number One: it’s the pictures that baffle and tantalise you that stay in the mind forever .'

By Country Life