My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon

'Lesson Number One: it’s the pictures that baffle and tantalise you that stay in the mind forever .'

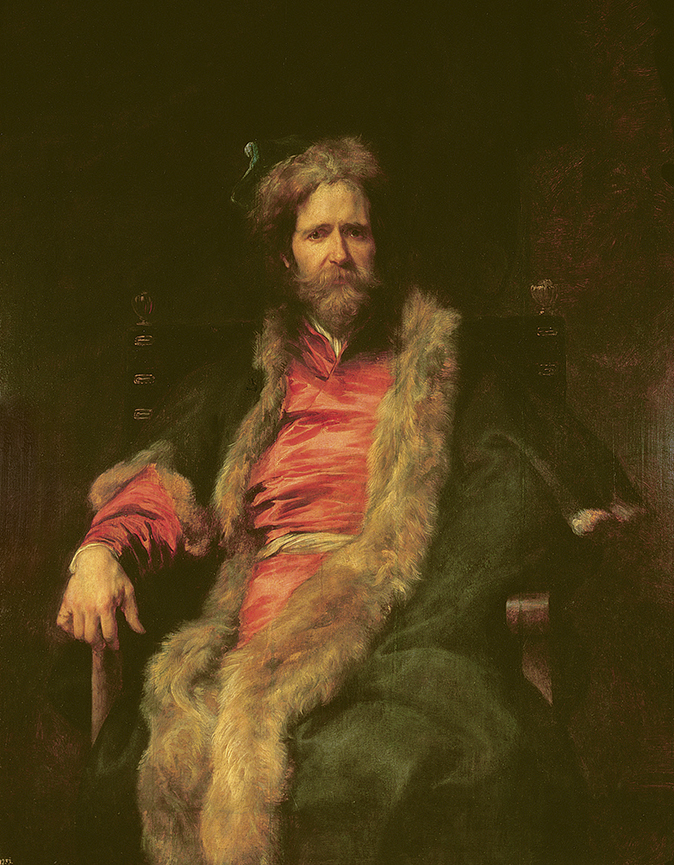

Andrew Graham-Dixon on why he chose Cupid and Psyche:

I remember my mother taking me to see this painting when I was a little boy. We used to feed the ducks in the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens and then go into Kensington Palace, where it used to hang (and still does, mostly). I suspect the tragic subject and sexual undertones – maybe that should be overtones – were lost on me. I was stunned by the colour and energy and excitement of the painting and by the sense that Something Important was going on, although what it might be I could not guess. Lesson Number One: it’s the pictures that baffle and tantalise you that stay in the mind forever .

Andrew Graham-Dixon is an art historian and broadcaster. You can find him at andrewgrahamdixon.com or on YouTube.

John McEwen comments on Cupid and Psyche:

Venus, goddess of love, was jealous of the beautiful, but mortal Psyche. She ordered Cupid, god of love, to make the girl fall for the most despicable of all men, but Cupid was secretly stricken by Psyche. He took her to an enchanted spot and visited her incognito every night. She promised him never to ask who he was, but, when she confided in her jealous sisters, they said he must be a monster to need to hide himself. Thus, when he slept, Psyche looked at him by the light of a lamp and saw he was gorgeous. He awoke and her betrayal was revealed. Venus enslaved and bullied her ceaselessly, but Cupid’s love was undimmed.

Van Dyck shows Psyche’s final labour for Venus – to deliver a casket from the Underworld containing the secret of Proserpine’s beauty. Psyche disobeyed by opening the casket and Venus struck her insensate; the flourishing and the dead tree in the picture symbolise her living-dead state. Cupid arrived and saved her from the spell with his arrow.

In 1637, there was a recital at Charles I’s Court of Shackerley Marmion’s epic poem Cupid and Psyche. The story behind van Dyck’s picture would have been fresh in the memory of his regal audience: the lovers fled to Mount Olympus, where Jupiter sanctioned their marriage, Psyche was immortalised and they lived happily ever after. Love conquers all.

Van Dyck chose a scene to illustrate Plato’s definition of ideal love, ‘desire aroused by beauty’. As Court painter, he made several mythological pictures for the King. This is the only one known to have survived.

This article originally appeared in 2018.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

My favourite painting: Bendor Grosvenor

'This penetrating depiction of triumph over adversity never fails to move me.'

Credit: The Restoration of Charles II - 17th century engraving, Victorian colouring

The fascinating story of the 'lost' royal art collections of Charles I and Charles II

The royal art collections of Charles I and Charles II were scattered across Europe – and after the Restoration, huge efforts

My favourite painting: David Starkey

David Starkey shares the one painting he would own, if he could

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

The designer's room: How rare, 19th-century wallpaper was repurposed inside a Grade I-listed apartment complex on London's Piccadilly

The designer's room: How rare, 19th-century wallpaper was repurposed inside a Grade I-listed apartment complex on London's PiccadillyThis home in Albany, Piccadilly, was decorated by Wendy Nicholls of Sibyl Colefax & John Fowler, as a quiet refuge in the heart of the capital.

-

The heroine's name in 'Rebecca' and a strange coffee subsitute: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 2, 2025

The heroine's name in 'Rebecca' and a strange coffee subsitute: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 2, 2025Friday's Quiz of the Day has a rock legend, a delicate flower and much more.

-

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite painting

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite paintingAlexia Robinson, founder of Love British Food, chooses an Edwin Landseer classic.

-

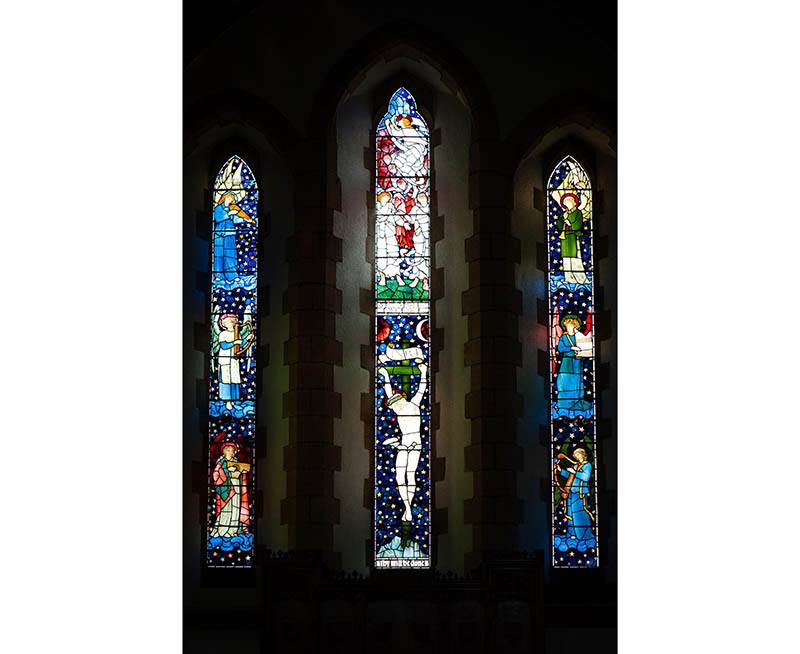

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in Britain

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in BritainThe painter Edward Burne-Jones turned from paint to glass for much of his career. James Hughes, director of the Victorian Society, chooses a glass masterpiece by Burne-Jones as his favourite 'painting'.

-

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subject

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subjectFor Country Life's My Favourite Painting slot, the writer Emily Howes chooses a work by a daring and challenging artist: Frank Auerbach.

-

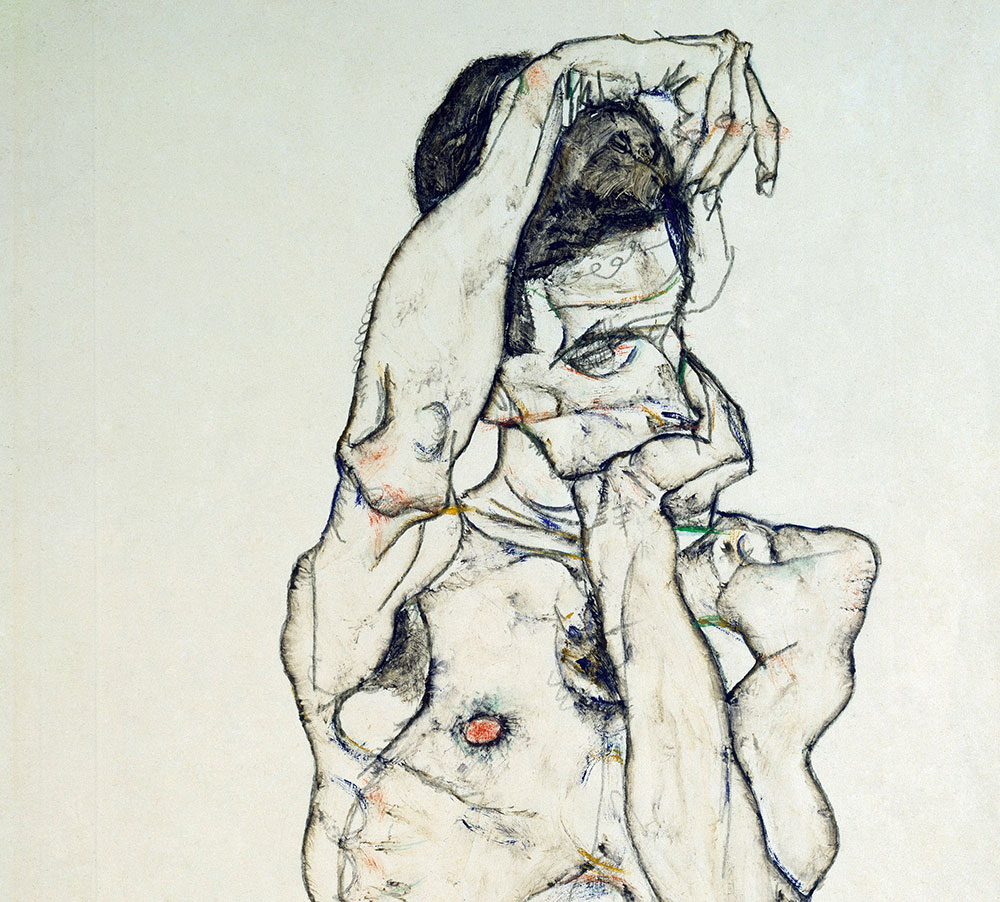

My Favourite Painting: Rob Houchen

My Favourite Painting: Rob HouchenThe actor Rob Houchen chooses a bold and challenging Egon Schiele work.

-

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson'That's why this is my favourite painting. Because it invites you to imagine'

-

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shock

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shockAs the National Gallery turns 200, the chair of its board of trustees, John Booth, chooses his favourite painting.

-

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearing

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearingChristopher Price of the Rare Breed Survival Trust on the bucolic beauty of The Magic Apple Tree by Samuel Palmer, which he nominates as his favourite painting.

-

My favourite painting: Sir Alistair Spalding

My favourite painting: Sir Alistair SpaldingThe artistic director of Sadler's Wells chooses a painting created 'purely to aid reflection and contemplation'.