'We moved here to be in a remote area, but there are 1,000 cars and motorhomes passing my house every day. It’s like Disneyland': How Scotland's best roads are causing local people the biggest headaches

10 years after it was established, the North Coast 500 continues to divide opinion. More tourism means more money, but for those who live along the route, their peaceful lives have been turned upside down. Matthew MacConnell investigates.

What comes to mind when you picture the Scottish Highlands? Razor-edged mountains topped with snow, framing deep valleys and lochs? Perhaps Highland cattle or the droning of bagpipes, filling the air with pride? Or is that air filled with exhaust fumes and the sound of frustrated drivers in traffic? Such is the paradox of the North Coast 500 (NC500).

In essence, the route is 516 miles of dreamy sci-fi-like landscape that crams in nearly everything the Highlands have to offer. Whether you’re an animal spotter, mountain climber, swimmer or a history buff, there’s something for almost anyone.

But it’s also one that’s currently steeped in controversy. Speaking to Country Life, one resident described the route and its popularity as ‘an absolute plague’. Another said her dream of a quiet life is now ‘a Disneyland for 8 months of the year’. How do you reconcile the benefits of tourism with the misery of locals who say they feel overwhelmed?

Before the route came to be, it’s claimed that Highland tourists would mostly visit Inverness and then return home, to the detriment of businesses further north. In 2013, the North Highlands Initiative, Highland Council, Highlands & Islands Enterprise, and VisitScotland came up with an idea to help push tourists north, and they called it the NC500. The route opened in 2015 and became an instant global success.

Being both Scottish and a journalist, whenever I attend work events, the NC500 and haggis often pop up. Telling people that I’ve only fully completed the NC500 once and that I usually find haggis to be a bit ‘meh’ understandably raises a few eyebrows. I’ve had a great time gliding a bodacious Bentley Continental GT S over many of the roads. I’ve also driven a Ford Ka packed to the brim with people and luggage. Both were immensely entertaining experiences.

The truth is, however, that driving the route requires thorough planning and reviewing your options, as it’s often filled with unpleasant surprises like traffic jams and road closures. On a positive note, the slower you go, the more likely it is to spot animals such as the pine marten. And the haggis? Well, that always tastes better in the Highlands.

But the route can also be bittersweet. Visit during peak tourist season (June to August), and you’ll no doubt find yourself running an unsolicited gauntlet at some point. The areas worth mentioning here are the A9 North to Wick, the Beleach na Bà pass and many of the single-track roads. Masses of motorhomes and slower traffic cause other drivers to become impatient, resulting in people being zealous when overtaking. More accidents and further road closures.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The wild landscape and single track roads near Clachtoll, in Assynt, on the North Coast 500.

‘The NC500 route can be quite a demanding route for people who are not used to driving in landscapes like that. It attracts people who want to be on open roads, but it’s all about education,’ says Eann Sinclair, Caithness and Sutherland area manager of Highlands and Islands Enterprises (HIE). ‘However, that education process doesn’t happen overnight and every time there’s an accident, it ramps up the feeling in local populations that it’s happening to them rather than with them.’

The roads, when clear, are astonishing. Those that stood out were the A836 and the Assynt Region: sections of tarmac are smooth, corners satisfyingly sweep, and long stretches cut through vast greenery and peaked mountains. The road dynamic can change swiftly with steep inclines and drops, sharp bends and massive bridges, adding even more fuel to the NC500’s spark.

Experiencing this in a convertible took things to another level. Dropping the top and breathing in the clean Highland air as I soaked up the route and the landscape will live long in my memory.

As will the Highland’s oddball weather cycles. One minute, I was enjoying blue skies and 20-degree heat. 10 minutes later, a downpour forced everyone sitting outside pubs to scurry inside with their pints. It was fun to watch, and it provided for dramatic photography as the clouds finally settled over the munros, corbetts and grahams.

Driving, scenery and refreshments. After sightseeing and driving for hours, one of my favourite things to do was sit by a fire in a cosy B&B while eating locally caught pike and sipping on smoky Lagavulin 16-year-old whisky.

I was often deep in thought at this point about what I’d seen — the birds of prey, the local I spoke to who briefed me about their Highland family history, and how these jagged hills are so beautifully carved. I also had a sense of fulfilment. I had given a local B&B some business, something that means a lot to business owners in the North Highlands who rely on tourism to stay afloat.

But this is a double-edged sword. There is litter and there is noise. People drive over flowerbeds and grass and park in front of fire stations.

"Where I live is paradise and when the NC500 was first introduced, I thought it was great. The idea of me sharing this stunning view I had with other people felt good. Now, the stream of traffic on the single-track road near me is awful, and the noise just echoes backwards and forwards off the hills as people squeeze their way past each other. The NC500 is an absolute plague"

Susanne Ramacher moved to Loch Eriboll after falling in love with the Scottish Highlands. ‘During peak season, there are at least 1,000 cars and motorhomes passing my house every day,’ she says. ‘We moved here because we wanted to be in a remote area, but now it’s a Disneyland for eight months of the year. One large issue is the open fires — this is a peat area. Even if the tourists pour water over the fire they’ve lit, it can still burn for six hours or so underneath. Likewise, there’s a graveyard near us and I often also find white tissues everywhere from those who camp and have BBQs there — it's incredibly disrespectful. I see my dream dying.’

The NC500 is a home to many who have lived the quiet Highland life for years. Another resident shared: ‘I’ve lived here for 32 years. Where I live is paradise; I have a beautiful view and when the NC500 was first introduced, I thought it was great. The idea of me sharing this stunning view I had with other people felt good.’

‘Now, the stream of traffic on the single-track road near me is awful, and the noise just echoes backwards and forwards off the hills as people squeeze their way past each other. The NC500 is an absolute plague and it’s taken away our quality of life.’

But what if you own a business on the route? Prior to the NC500, many restaurants, bars, hotels and B&Bs would close over the winter months, relying on revenue when the tourist season arrived. It was not sustainable for many. The NC500 now brings in customers all year.

According to reports, it was worth more than £22m to the local economy in 2018. An economic baseline study held by the North Highland Initiative showed that businesses had experienced a 15-20% trade increase. ‘It’s been interesting to see how many new businesses it’s generated over the last few years. Of course, the NC500 also came through the Covid period, and it’s still going strong — it's remarkable,’ says Eann.

Ullapool, on the shores of Lochbroom.

More business might mean more money, but it’s not obvious where it’s going. ‘All I hear is “it brings money to the communities”, but they closed 24 of 28 public toilets in the North Highlands because there was no money,’ says Susanne. ‘The roads are also in terrible condition because there's no money to fix them either.’ According to VisitScotland, £20 million of Scottish Government funding has been distributed into projects across Scotland through the Rural Tourism Infrastructure Fund. Some of this money has been spent around the NC500, such as providing parking, public toilets, and motorhome facilities.

But from my experience, there are few public toilets on the route, and the ones that are open often fall into disarray. I saw lots cars parked in laybys and people scurrying into bushes. The single-track roads often have few passing places and judging what's coming around a corner is difficult because of large hills, humpback bridges, tall bushes and trees. Parked cars in single-track roads means more traffic.

So what can be done? The roads won’t be getting wider anytime soon, and even if they were, that would hardly satiate residents already complaining about noise. A tourist cap is unenforceable. Traffic lights? ‘There's no light pollution here - it's great. We don't want traffic lights,’ Susanne says.

The only answer at the moment is to try and spread the visitors out. ‘For several years now, our strategy has been on growing the value of tourism rather than the volume of our visitors to Scotland,’ says Chris Taylor, the destination development director at VisitScotland. ‘Our marketing activity focuses on promoting the country as a year-round destination, inspiring visitors to visit at different times of the year or areas with capacity, and slow down and immerse themselves in the destinations they are visiting.’

VisitScotland also added that they are working ‘with local partners to understand the opportunities and impacts in specific communities which informs our planned activity.’

The Highlands of Scotland is one of the most beautiful places in the world. And one of the most beautiful ways to see it is by car. People bring money, but they also bring everything else. For VisitScotland and the local economy, it might be a nice problem to have. But for those that live there, it’s just a problem.

Matthew MacConnell is a motoring journalist who has written for Forbes, Fleet World, The Drive, and Classic Car Weekly. He also likes to natter about vans, trucks, and electric bikes

-

RHS Chelsea Flower Show: Everything you need to know, plus our top tips and tricks

RHS Chelsea Flower Show: Everything you need to know, plus our top tips and tricksCountry Life editors and contributor share their tips and tricks for making the most of Chelsea.

By Amie Elizabeth White

-

Hidden excellence in a £7.5 million north London home

Hidden excellence in a £7.5 million north London homeBehind the traditional façades of Provost Road, you will find something very special.

By James Fisher

-

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old Masters

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old MastersThe younger generations’ appetite for everything vintage bodes well for the future, says Huon Mallalieu, at a time when an extraordinary Old Masters collection is about to go under the hammer.

By Huon Mallalieu

-

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication'The Great Gatsby' sold poorly the year it was published, but, in the following century, it went on to become a cornerstone of world literature.

By Carla Passino

-

Shark tanks, crocodile lagoons, laser defences, and a subterranean shooting gallery — nothing is impossible when making the ultimate garage

Shark tanks, crocodile lagoons, laser defences, and a subterranean shooting gallery — nothing is impossible when making the ultimate garageTo collectors, cars are more than just transport — they are works of art. And the buildings used to store them are starting to resemble galleries.

By Adam Hay-Nicholls

-

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of spring

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of springThe biggest-ever David Hockney show has opened inside the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris — in time for the season that the artist has become synonymous with.

By Amy Serafin

-

Under the hammer: A pair of Van Cleef & Arpels earrings with an intriguing connection to Princess Grace of Monaco

Under the hammer: A pair of Van Cleef & Arpels earrings with an intriguing connection to Princess Grace of MonacoA pair of platinum, pearl and diamond earrings of the same design, maker and period as those commissioned for Grace Kelly’s wedding head to auction.

By Rosie Paterson

-

Why LOEWE decided to reimagine the teapot, 25 great designs over

Why LOEWE decided to reimagine the teapot, 25 great designs overLoewe has commissioned 25 world-leading artists to design a teapot, in time for Salone del Mobile.

By Amie Elizabeth White

-

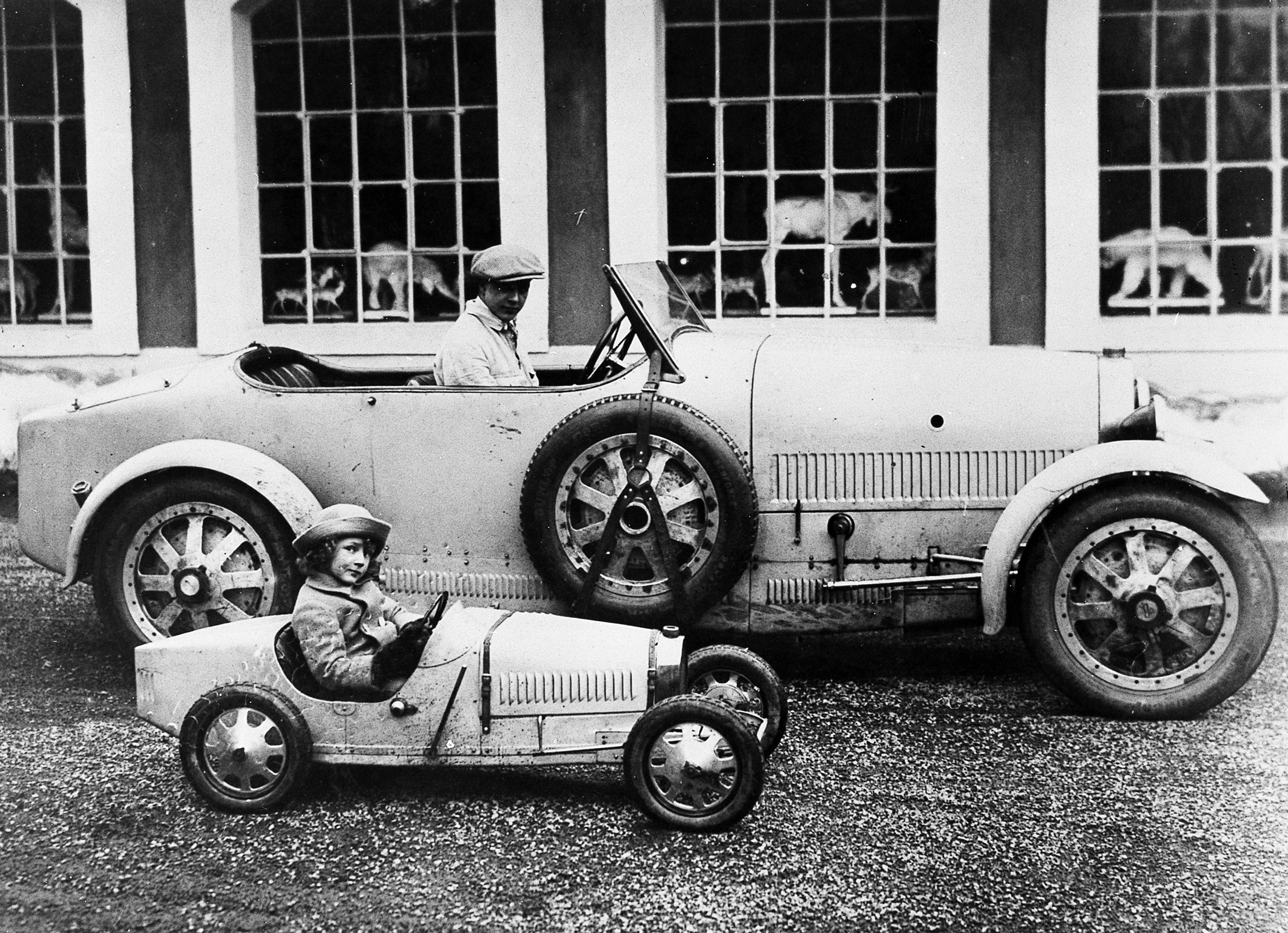

The brilliant Bugattis: Sculpture, silverware, furniture and the fastest cars in the world

The brilliant Bugattis: Sculpture, silverware, furniture and the fastest cars in the worldA new exhibition at this year's Treasure House Fair will shine a light on the many talents of the Bugatti dynasty.

By James Fisher

-

Big, bright and bold: Colourful luggage to inspire your next spring getaway

Big, bright and bold: Colourful luggage to inspire your next spring getawayIf RIMOWA's new 'Holiday' campaign is anything to go by, then conservative-coloured luggage is out and eye-catching is in.

By Rosie Paterson