Curious Questions: Who made the first proper car journey?

The man who invented the very first motor car didn't think it would be able to survive a long-distance car journey. Luckily, his wife had more faith, as Martin Fone discovered when he investigated the tale of Bertha Benz.

I have long been fascinated by inventors. What came through in the stories of some of the male inventors featured in my recent book, The Fickle Finger, was the role that their wives played. For every horrified Frau Röntgen — who, when shown the first X-ray, exclaimed ‘I have seen my death’ — there was at least one Elma Farnsworth, who fought tooth and nail to establish Philo T. Farnsworth’s reputation as a father of television, and secure the financial rewards his ingenuity merited.

Some thought that the application of a well-aimed boot to the seat of their husband’s lederhosen was needed to spur them on. Bertha Benz was one such.

Her husband, Karl, an innovative engineer fascinated by locomotion, had by 1880 developed and patented a two-stroke engine and then a speed regulation system, together with a spark plug, carburettor, clutch, gear stick and radiator. Benz was not content to stop there. His ambition was to develop a horseless carriage, a vehicle designed to move using its own power.

What he created was the Benz Patent Motorwagen, boasting a four-stroke engine nestling between the rear wheels, power transmitted to the rear axle by two chains, and an evaporative cooling system. It too was patented, on January 29, 1886, described as an ‘automobile fuelled by gas’. Although difficult to control — it crashed into a wall during an early public demonstration — Benz did manage to tame his beast sufficiently to complete some road trials successfully later that year. Dissatisfied with the vehicle’s technical specification, Karl incorporated several modifications into a Model 2 and by 1888 the definitive Model 3 was being finalised.

Inventing something is one thing, however; making money out of it is another. Although a brilliant, innovative mechanical engineer, Karl was not much of a businessman. Bertha was becoming increasingly frustrated by the slow progress he was making in marketing his revolutionary Motorwagen and decided to take matters into her own hands. What was needed to put the doubters in their place and demonstrate the machine’s worth was proof positive that it was reliable and capable of negotiating a long journey.

Bertha’s idea was to take the Model 3 on a lengthy test drive from their base in Mannheim, but where to? The town of her birth, Pforzheim, around 65 miles away as an inebriated crow flies, seemed the obvious choice, especially as Bertha had decided to keep the proposed trip secret from her husband. A visit to her family would give her the perfect cover.

"An engine generating around 2.4 horsepower simply did not have enough oomph to get up anything other than the gentlest of inclines... The only option was to get out and push"

Waiting until the school holidays had begun and inveigling her two sons, Eugen and Richard, into the plot, Bertha sprang into action on August 5, 1888. Leaving Karl asleep in bed and a note on the kitchen table informing him that she had gone to Pforzheim, she and her sons crept out of the house. They pushed the Model 3 out of the workshop to a spot where it was safe enough to start the contraption without fear of waking the inventor. The first long-distance motor journey had begun.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Karl, on getting up and finding the note, went out to the workshop and discovered that his pride and joy had gone. Bertha did have the grace to set his mind at rest by sending him telegrams, the late 19th century equivalent of text messages, as their journey progressed.

At best, her progress could be described as stately. Even when motoring had become an established pursuit at the turn of the 20th century, it was not the comfortable experience that we enjoy today. As Arnold Bennett commented in The Card (1911), ‘this was in the days… when automobilists made their wills and took food supplies before setting forth’.

For the very first motoring pioneer, the obstacles Bertha had to overcome would have defeated a less intrepid and determined person. How was she to find way to Pforzheim? As there were no autobahns and signage was, at best, rudimentary and localised, she played safe by eschewing the most direct route and passing through Weinheim, Wiesloch, Langenbrücken, and Bruchsal, all towns known to her, before reaching Pforzheim.

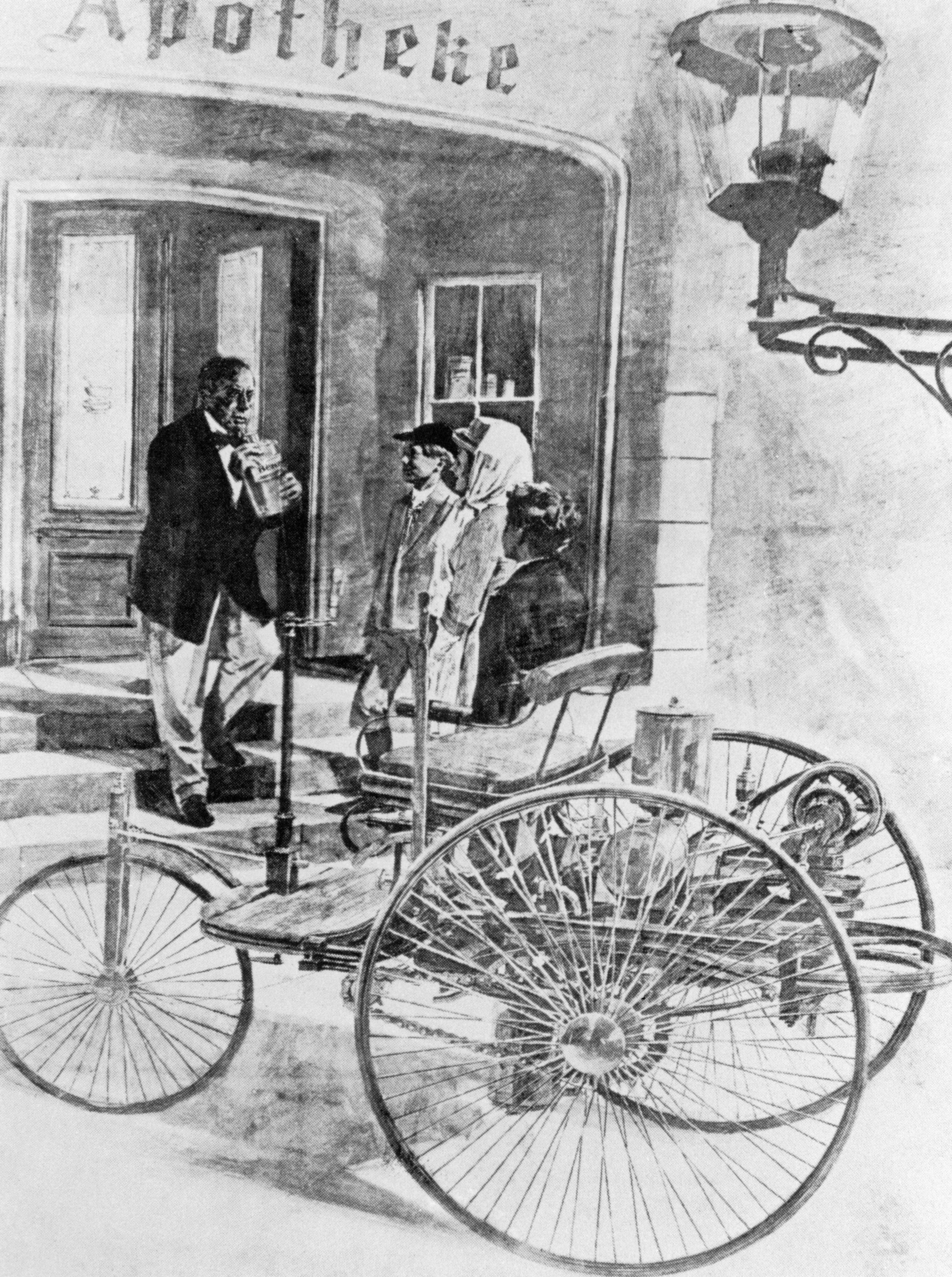

Fuel was another concern. The vehicle did not have a petrol tank, just a fuel reserve of just 4.5 litres in the carburettor. Obviously, there were no petrol stations. The only place to purchase ‘ligroin’, as petrol was known then, was at a pharmacy. Bertha’s first port of call in Wiesloch can rightly claim to be the first fuelling station in motoring history, and the shop she stopped at is still there today. Two more visits, again to chemists’ shops, were required before the journey’s end.

The engine was cooled by water which absorbed heat and evaporated. The drawback, though, was that the water level had to be topped up regularly, necessitating frequent stops at public houses, streams and even ditches.

And then there were the hills. An engine generating around 2.4 horsepower with just a two-speed gear box simply did not have enough oomph to get up anything other than the gentlest of inclines under its own volition. The only option was to get out and push. By the time they got to a hill near Wolferdingen, Bertha and her sons were so exhausted that they had to call upon the assistance of a couple of young farm hands. What they thought is not recorded.

Descending hills was no breeze either. It took a considerable effort to pull the lever at the side of the vehicle to put on the brakes. Even more alarmingly, the brake shoes quickly wore out. Ever resourceful, Bertha even had time, on the return journey, to invent brake linings, persuading a cobbler in Bauschlott to cover the shoes with leather.

A blocked fuel line (cleaned using her hat pin) and a worn-out ignition wire (insulated with her garter) were but minor irritations to Bertha. At least she didn’t have to worry about getting a flat tyre: the rear wheels were solid iron, the front were iron covered in solid rubber. By dusk, though, the intrepid trio had reached Pforzheim after a 12-hour journey and, after a few days’ recuperation, made the return journey, this time taking a more direct route.

Bertha’s enterprise in attempting the 180-kilometre round trip proved to the sceptics that the motor car had a future. No doubt at his wife’s insistence, Karl added an extra gear and more effective brakes to the Model 3 and in the late summer he began selling what was the first commercially available car. A Parisian bicycle manufacturer, Emile Roger, who manufactured Benz engines under licence, bought a Motorwagen, the second to be sold. Granted an exclusive agency, Roger proved a more effective salesman than Karl and of those that were sold, most had French owners.

The only Model 3 that remains today — alas, not the one driven by Bertha — is owned by the Science Museum in London, who have loaned it out to the Benz Museum in Ladenburg. Should you fancy retracing her steps, you can: The Bertha Benz Memorial Route, her original route, was declared a European Route of Industrial Heritage in 2008.

Motoring has since moved out of the slow lane, but it owes a big debt of gratitude to Bertha.

Credit: Getty

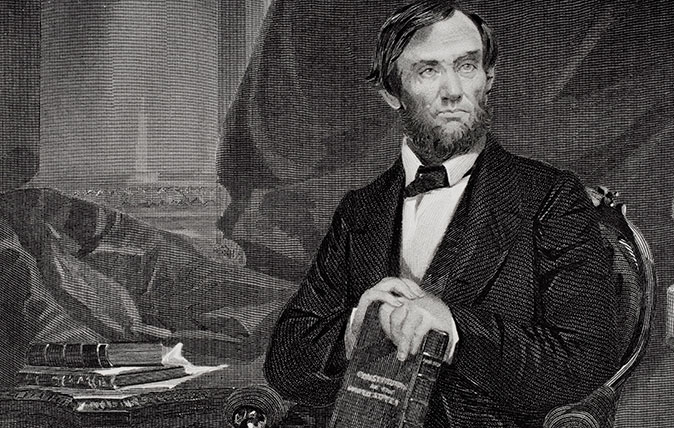

Curious Questions: How did Abraham Lincoln come to be the only US president to hold a patent?

Statesman, lawyer, fearless leader – and part-time inventor. Martin Fone looks at one of Abraham Lincoln's lesser-known talents.

Credit: Melanie Johnson

Why is pancake day called 'Shrove Tuesday'?

Martin Fone investigates how Shrove Tuesday got its name — and also unveils the history of the day that precedes it,

Credit: Alamy

Curious questions: Are you really never more than six feet away from a rat?

It's an oft-repeated truisim about rats, but is there any truth in it? Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions',

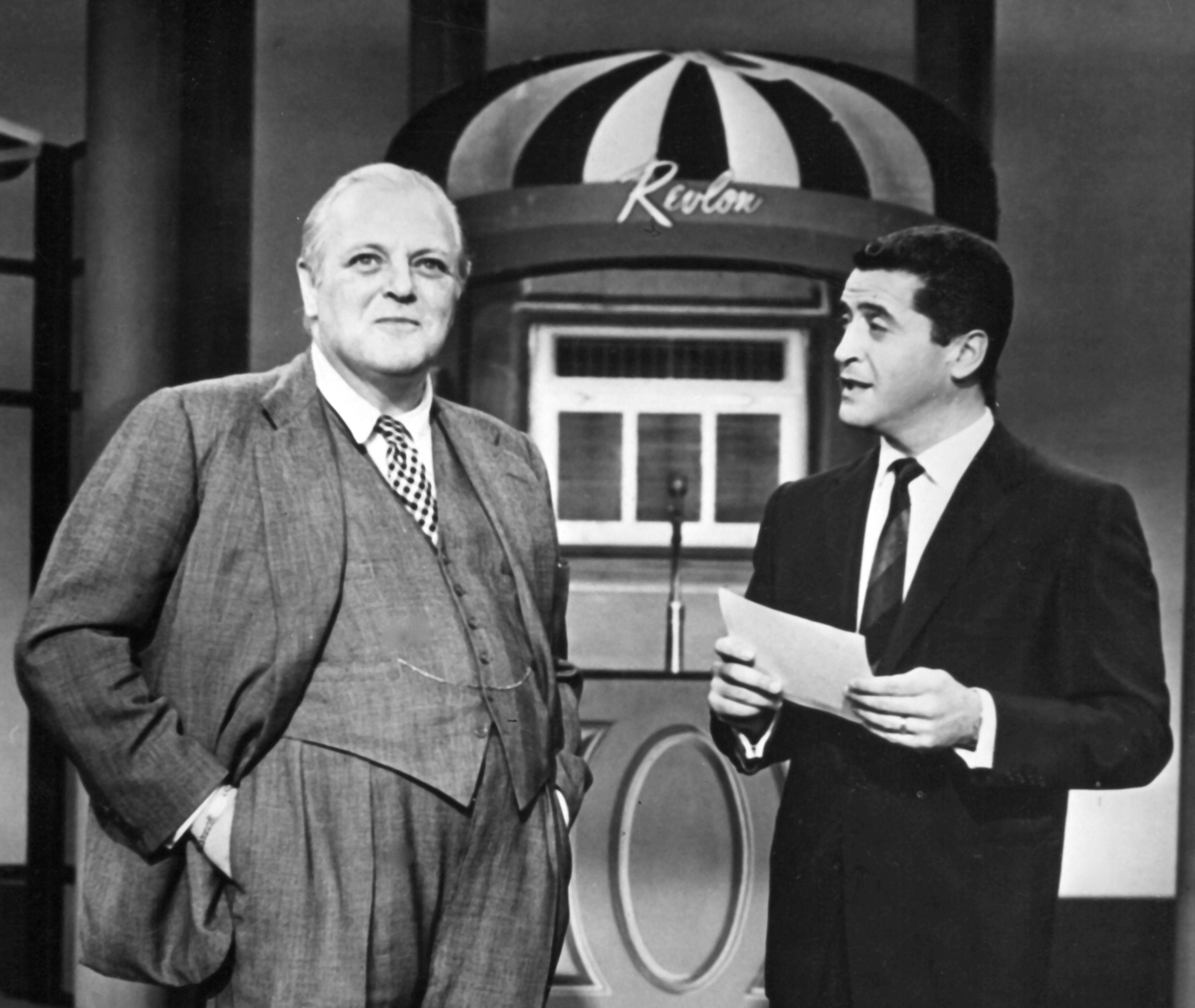

Curious Questions: Why do we talk about the '$64,000 question' — even in a country where we don't use dollars?

A question about a question? Absolutely. Martin Fone gets to the bottom of where this curious phrase originates — and how

Credit: Morgan Hancock / Getty

Curious Questions: Why do cricketers call it a 'duck' when they get bowled out for 0?

Martin Fone, author of 50 Curious Questions, explains how a duck egg led to the popularisation of a term in

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.