Banning sale of fossil fuel cars from 2035 is the right thing to do — but countryside pressures could keep the diesel pumping for decades after that

The future of cars is electric — can ONLY be electric, eventually — but the timetable for us to switch over could take a lot longer than you might think. We take a look at the ramifications of the government's 2035 deadline for banning the sale of diesel and petrol-powered automobiles.

I recently took charge of an endangered species, a creature that has thrived for over half a century but which now faces a dark future. This was no a rare breed of dog, however, nor a loft full of bats: it was a diesel-powered 4x4.

The Mitsubishi Shogun Sport is a huge car, with a cabin so big that you could host a tea party in it. It's nicely-appointed, good to drive, enormously capable off-road, can tow more than three tonnes and — unlike many alternatives — can be had for under £30,000.

There's one more thing: from 2035, it will no longer be legal for new cars such as the Shogun to be sold in the UK. And while in some ways 2035 sounds a long way away, in other ways it's incredibly close. After all, it's only as far up the road as 2005 is in the rear view mirror — and that really doesn't seem all that long ago.

The government's policy was unveiled as part of the launch event of COP26, the annual UN gathering to discuss climate change, which will be held in Glasgow in November. The plan will be subject to a consultation, but it's unlikely to change: it comes after climate experts said that the previous target of 2040 was too late if the UK intends to stick to its goal to be emitting almost zero carbon by 2050.

What's more, it is no half-measure: hybrid vehicles are also included under the new proposals, meaning that people will only be allowed to buy fully electric or hydrogen cars and vans.

We entirely understand the rationale. The future of cars will be electric — it can only be electric — and that has to start somewhere.

There are naysayers, of course. Many people argue that, at present, electric cars do more harm than good to the environment, raising concerns over the true cost of battery production and suggesting that, given the current state of renewable energy, switching from gasoline or diesel to electricity actually involves burning more coal and natural gas.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

But the counter-arguments are stronger. Battery technology is probably where internal combustion technology was in 1900, and will certainly evolve and improve. Latest figures suggest that electric cars are cleaner even when they rely on coal — especially when you factor in urban air quality, and the impact of fumes belched out at street level compared to the clouds emitted by far-distant chimneys.

The big question hangs over the speed of adoption of electric vehicles under the government's plans, which drew criticism from a variety of pressure groups, with the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders accusing the Prime Minister of ‘moving the goalposts for consumers and industry on such a critical issue’.

The organisation’s chief executive Mike Hawes added that: ‘We need to hear how the Government plans to fulfill its ambitions in a sustainable way, one that safeguards industry and jobs, allows people from all income groups and regions to adapt and benefit and, crucially, does not undermine sales of today’s low-emission technologies, including popular hybrids, all of which are essential to deliver air-quality and climate-change goals now.’

Countryside groups have also voiced concerns, with worries about infrastructure chief among them. ‘It’s a very laudable objective, but how will this happen across the countryside?’ says CLA president Mark Bridgeman.

‘Distances vehicles travel in rural areas is often greater than urban. Some rural vehicles are regularly used for towing trailers and, therefore, require high output engines with appropriate gearing.

‘However, by far the most concerning factor is the lack of infrastructure for vehicle charging, as well as the excessive cost of providing charging points, which makes provision unviable, so network reform is needed and how charging for capacity is decided needs review,’ he continued.

This is a huge infrastructure project. According to Scottish Power, the UK will need 25 million electric vehicle chargers by 2050. As of the time of writing, there are over 30,500 charging points at just under 11,000 locations, according to the website www.zap-map.com.

‘Objectives are good, but delivery is what counts and the countryside should not be left behind,' added Bridgeman. And that is the heart of the issue: it's already straightforward to be an electric car owner in and around the M25, but it's more or less impossible as things stand to run an electric-only car in places such as the West Country or the Highlands.

Putting in those 25 million electric car chargers is a colossal project, but such things have been done before. It'll be trickier than the switch to unleaded petrol in the 1980s, but it'll certainly be simpler than the huge-scale installation of natural gas pipes across Britain in the 1960s.

But there's one other worry: finding enough drivers who can afford to buy the new cars to plug into those charging points. Unlike the modestly-priced Mitsubishi Shogun Sport, electric cars are currently hugely expensive; prohibitively so for most. The NFU has warned that low-income households in the countryside will be hardest hit, places where a car is a necessity rather than a luxury (such households are 70% more likely to have a car than urban low-income households).

Most of those people in the country currently drive second-hand diesel cars, which can be had for a few hundred quid and kept running for many years. We don't yet know whether electric cars — and in particular their batteries — will be able to do the same. And if not, the petrol stations selling fossil fuels will probably have to keep on pumping for many years — possibly many decades — after that 2035 deadline has come and gone.

Additional reporting by James Fisher

Credit: Jaguar

The five best electric cars you can buy today, no matter what you need

It doesn't matter if you need a sporty car, a city hatchback or a load-lugger with room for all the

Credit: Richard Parsons

The Jaguar I-Pace: 'If I had a spare £65,000, I’d buy one tomorrow. It really is that good'

That Jaguar’s all-electric I-Pace is the 2019 World Car of the Year comes as no surprise to Mark Hedges.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

The bright idea that's a 'landmark moment' for electric cars in Britain

One of the major headaches of owning an electric car is finding and paying for a charging point — but that's

Credit: Getty Images/Tetra images

Country Life Today: The great electric car debate — could they really be worse than diesel?

Toby Keel is Country Life's Digital Director, and has been running the website and social media channels since 2016. A former sports journalist, he writes about property, cars, lifestyle, travel, nature.

-

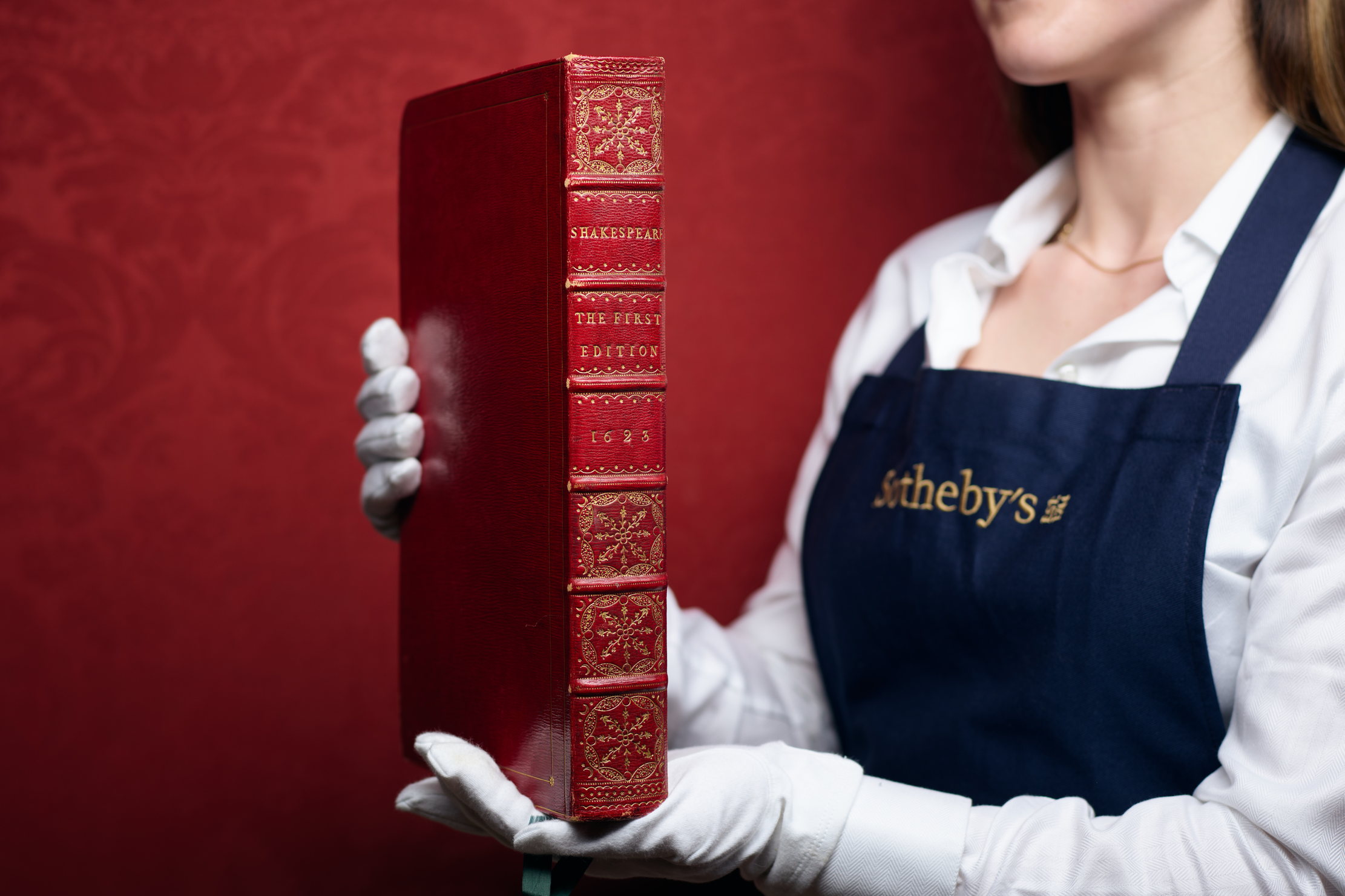

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby's

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby'sFour Folios will be auctioned in London on May 23, with an estimate of £3.5–£4.5 million for 'the most significant publication in the history of English literature'.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow down

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow downThe glorious Andalusian-style villa is found within the Lomas de Marbella Club and just a short walk from the beach.

By James Fisher