Materials, textures, construction, expression: A Brutalist watch on your wrist

Luxury watchmakers are seeking to bridge the gap between two contrasting styles, with exciting results.

It’s an odd question, when you think about it. Can a luxury watch be Brutalist? Some have a basic practicality in their ancestry — watches that originated in times of warfare, for example, were engineered for keeping time in the most hostile conditions. You could call them utilitarian, perhaps.

But Brutalist? Not only do many of them pre-date the term itself, but they struggle to evoke the very specific style that we associate with the movement, either in their original form or their present-day, more luxurious guise. Then you have the more opulent end of the spectrum, closer in aesthetic to a rococo state ballroom than a concrete car park. There’s nothing brutal about a Bovet or a Breguet, except perhaps occasionally the price.

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) defines Brutalism as ‘a style with an emphasis on materials, textures and construction, producing highly expressive forms’. That sounds a bit closer to home, horologically speaking — but it’s also quite broad.

The material in question is usually concrete (beton brut being the French term), as beloved of architects like Le Corbusier who in a curious coincidence — for our purposes at least — was born in La Chaux de Fonds, the Jura town best known as the cradle of traditional Swiss watchmaking. And the ‘emphasis on construction’ tended to mean exposed air vents and chimney stacks. Watchmakers like showing off their movements, but again, it’s not quite the same thing.

'If there’s so little common ground between the massive, slab-sided form of the National Theatre and the polished flanks of a Rolex Day-Date, why connect the two?'

So why are we even asking the question in the first place? If there’s so little common ground between the massive, slab-sided form of the National Theatre and the polished flanks of a Rolex Day-Date, why connect the two? Because despite the potential chasm between them, several influential watchmakers have in recent times paid direct tribute to Brutalist styles, creating watches — and in one case, an entire brand — that they say are inspired by Brutalist architecture.

At the same time, we have also seen a spike in demand for blocky, angular, asymmetrical designs in the vintage world, such as the Rolex King Midas, a five-sided irregular dress watch with a tapered bracelet, first introduced in 1964.

The most high-profile modern example has come from Audemars Piguet, with its [Re]Master 02, which it labelled ‘a tribute to Brutalism. The watch is based on a design from 1960 known as reference 5159BA, and features a lop-sided, sharp-edged case shape with a multi-faceted crystal display (so unusual in its dimensions that AP had to carve out a slice from the inner left hand side to allow the minute hand to rotate properly).

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Audemars Piguet [Re]Master 02 — ‘a tribute to Brutalism'

It’s definitely a ‘highly expressive form’, to return to RIBA’s words, and anyone who has worn one will confirm that it is surprisingly massive — another Brutalist trait, and not an easy one to execute in wristwatch form. Texture is represented too, in its brushed ‘sand gold’ case, but pulling at this thread slightly undoes the 02’s Brutalist leanings, because like all fine watchmakers, Audemars Piguet takes particular care over the delicate surface finishing of its cases (and movements) and that’s rather at odds with brutalist notions of rough, crude exteriors.

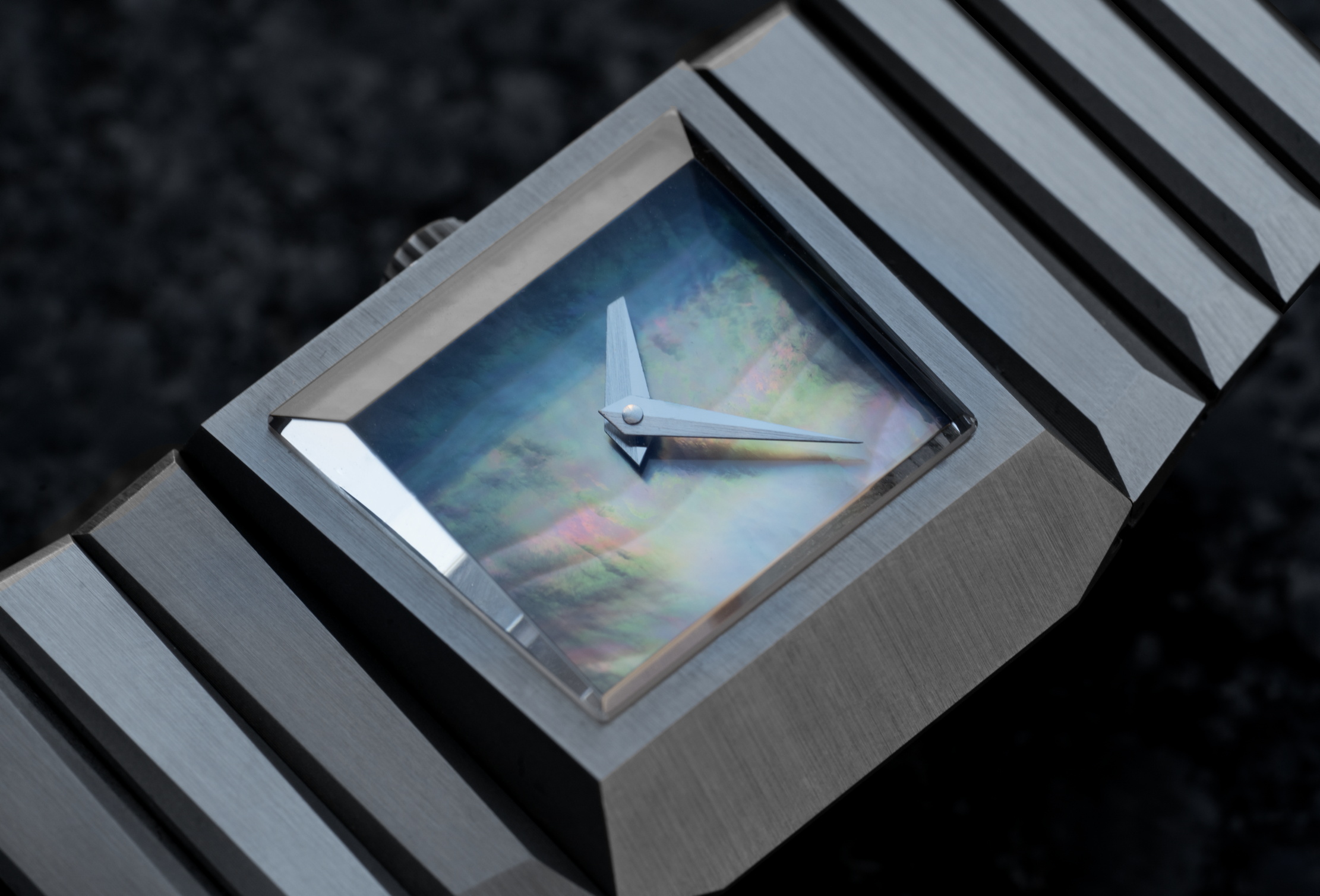

Another brand making a direct connection to Brutalist architecture is Toledano & Chan, the New York and Hong Kong indie start-up whose debut design, the B/1, is a direct homage to the Met Breuer building in New York, and specifically its asymmetric extruded windows. Founders Phil Toledano and Alfred Chan bonded over a love of Brutalism, among other things, and make perhaps the most credible link between a watch and the aesthetic.

In doing so, however, they aren’t taking an overly literal approach: the B/1 is still luxurious in familiar ways, from its bracelet polishing to its lapis lazuli or mother-of-pearl dials. ‘Architecture is highly adjacent to watch nerdery,’ says Toledano, and it’s clear that the watch design blends the two passions. The B/1 has also attracted its fair share of comparisons to the King Midas.

What about less retro-focussed brands? Richard Mille, whose watches typically use unconventional materials, exposed mechanisms and idiosyncratic shapes in the service of an aesthetic that’s more future-industrial than Brutalist, recently released an updated version of its RM 16-02 Extra Flat that it says ‘reinterprets the brand's well-established aesthetic codes, showcasing a resolutely Brutalist style with its straight lines and monolithic structure.’

The RM 16-02 Extra Flat by Richard Mille, which 'reinterprets the brand's well-established aesthetic codes, showcasing a resolutely Brutalist style with its straight lines and monolithic structure'.

From the front at least, the watch appears not to have a curved line to its name, although of course the requisite wheels and gears are still present. It has redesigned the movement’s dial-side plates, come up with a new typeface, and even re-routed the traditional minute track along a zig-zag path: the end result does rather look like an aerial view of a Brutalist city plan.

Other Swiss brands, or watches, possess elements that nod to Brutalism without going the whole way. Patek Philippe’s Cubitus is sufficiently rectangular and emphatic, but far too conventionally decorated; some small independent brands like Kollokium, Ochs & Junior, Lebond and Alto all flirt with various Brutalist-lite notions like rough textures, geometric cases, asymmetric shapes and minimalist blank surfaces, but none could truly be said to channel a Brutalist spirit.

Perhaps the conclusion is that luxury watchmaking can never quite overcome the ideological gap between its devotion to precision and adornment and real Brutalism’s rigid, undecorated principles. But the fact that watchmakers are even trying has given us some fascinating results.

Chris Hall is a freelance writer and editor specialising in watches and luxury. Formerly Senior Watch Editor for Mr Porter, his work has been published in the New York Times, Financial Times, Esquire, Wired, Wallpaper* and many other titles. He is also the founder of The Fourth Wheel, a weekly newsletter dedicated to the world of watches.

-

London Craft Week: Rolls-Royce demonstrates the true beauty of real artisanship

London Craft Week: Rolls-Royce demonstrates the true beauty of real artisanshipA triptych of British nature scenes show that the difference between manufacturing and art is not as wide as we might think.

-

Name that dog: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 13, 2025

Name that dog: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 13, 2025One of Britain's most picturesque streets and Tom Brown's school find their way in to Tuesday's quiz.

-

London Craft Week: Rolls-Royce demonstrates the true beauty of real artisanship

London Craft Week: Rolls-Royce demonstrates the true beauty of real artisanshipA triptych of British nature scenes show that the difference between manufacturing and art is not as wide as we might think.

-

A woolly mammoth skeleton is among the curiosities for sale to save fire-ravaged Parnham Park

A woolly mammoth skeleton is among the curiosities for sale to save fire-ravaged Parnham ParkThe auction of the owner James Perkins' collection, hosted by Dreweatts, tomorrow (May 13), will be used to fund renovation works at Parnham Park in Dorset.

-

The Swatch ScubAqua collection is ‘a Woolworths pick-and-mix counter for your wrist’

The Swatch ScubAqua collection is ‘a Woolworths pick-and-mix counter for your wrist’The 1990s wasn't horology’s most glittering decade, but with the decade firmly back in style, watchmakers are keen to give it all another go.

-

BMW X7 M60i: A car that can somehow do absolutely everything

BMW X7 M60i: A car that can somehow do absolutely everythingBMW's large luxury SUV pushes the very boundaries of the possible.

-

Kermit the frog, a silver-horned goat and Charles III’s 69ft-long coronation record star in a groundbreaking exhibition

Kermit the frog, a silver-horned goat and Charles III’s 69ft-long coronation record star in a groundbreaking exhibition‘Happy & Glorious’, at the The National Archives in Kew, captures the spirit of the King’s coronation with works by eight contemporary artists alongside the official roll of the day — and that of Edward II’s crowning in 1308.

-

The National Gallery rehang: 'It is a remarkable feat to hang more with the feeling of less', but the male gaze is still dominant

The National Gallery rehang: 'It is a remarkable feat to hang more with the feeling of less', but the male gaze is still dominantAlmost everything on display at the National Gallery has been moved — and paintings never previously seen brought out — in one of the the biggest curatorial changes in the Gallery's history.

-

The last ‘private’ photograph of F1 driver Ayrton Senna taken before his death goes on display in London

The last ‘private’ photograph of F1 driver Ayrton Senna taken before his death goes on display in LondonIn a new exhibition of Jon Nicholson’s work at Connolly, Mayfair, photographs of Earth’s most glamorous — and sometimes tragic — motorsport series are displayed alongside ones of ‘quintessentially British’ banger racing.

-

Lotus Emira Turbo SE: If you want to experience the last 'real' Lotus, now is the time

Lotus Emira Turbo SE: If you want to experience the last 'real' Lotus, now is the timeAs Lotus goes fully electric, we take out its last petrol offering, the Emira, to see if the spirit of Chapman is still alive.