In Focus: Why the eerie thrives in art and culture

The tradition of ‘eerie’ literature and art, invoking fear, unease and dread, has flourished in the shadows of British landscape culture for centuries, says Robert Macfarlane.

In July 1925, M. R. James published one of his most disturbing ghost stories, A View From A Hill. It begins on a hot June afternoon, when a Cambridge academic called Fanshawe arrives at the house of his friend Squire Richards, deep in the rural South-West of England. Richards proposes an evening walk to a nearby hilltop, from where they can ‘look over the country’.

Fanshawe asks if he can borrow some binoculars. After initial hesitation, Richards agrees — and gives Fanshawe a smooth wooden box. It contains, he explains, a pair of unusually heavy field-glasses, made by a local antiquary named Baxter, who died under mysterious circumstances a decade or so earlier. In opening the box, Fanshawe cuts his finger on one corner, drawing blood.

The two men go out for their walk up to the viewpoint, where they stop to survey the ‘lovely English landscape’ spread out beneath them: a ‘fertile plain’, ‘green wheat, hedges and pastureland’ and ‘scattered cottages’. The smell of hay is in the air, and there are ‘wild roses on bushes hard by’. Constable could have painted the scene into being. It is, writes James, ‘the acme of summer’ — the pinnacle of the English pastoral.

Then, however, Fanshawe raises the binoculars to his eyes — and that ‘lovely landscape’ is disturbingly disrupted. Viewed through the glasses, a distant wooded hilltop becomes a treeless ‘grass field’, in which stands a gibbet, from which hangs a body. There is a cart containing other men near to the gibbet. People are moving around on the field.

When Fanshawe takes the binoculars from his eyes, the gibbet vanishes and the innocent wood returns. Up, ghostly; down, lovely. Up, corpse; down, copse. He explains it away as a trick of the midsummer light. From there the story takes further sinister turns, however.

The next day, Fanshawe bicycles out to ‘Gallows Hill’, as it is locally called, to investigate the illusion. In the wood on the hilltop, he becomes convinced that there is someone watching him from the thicket, and ‘not with any pleasant intent’. Panicking, he flees.

Eventually the grim secret of the binoculars is revealed. The antiquary Baxter had filled their barrels with a fluid derived by boiling the bones of hanged men, whose bodies he had plundered from the graves on Gallows Hill, formerly a site of execution.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In looking through the field-glasses, Fanshawe was ‘looking through dead men’s eyes’ — and summoning violent pasts into visible being. Prospect was a form of retrospect; Baxter’s macabre optics revealed the skull beneath the skin of the countryside.

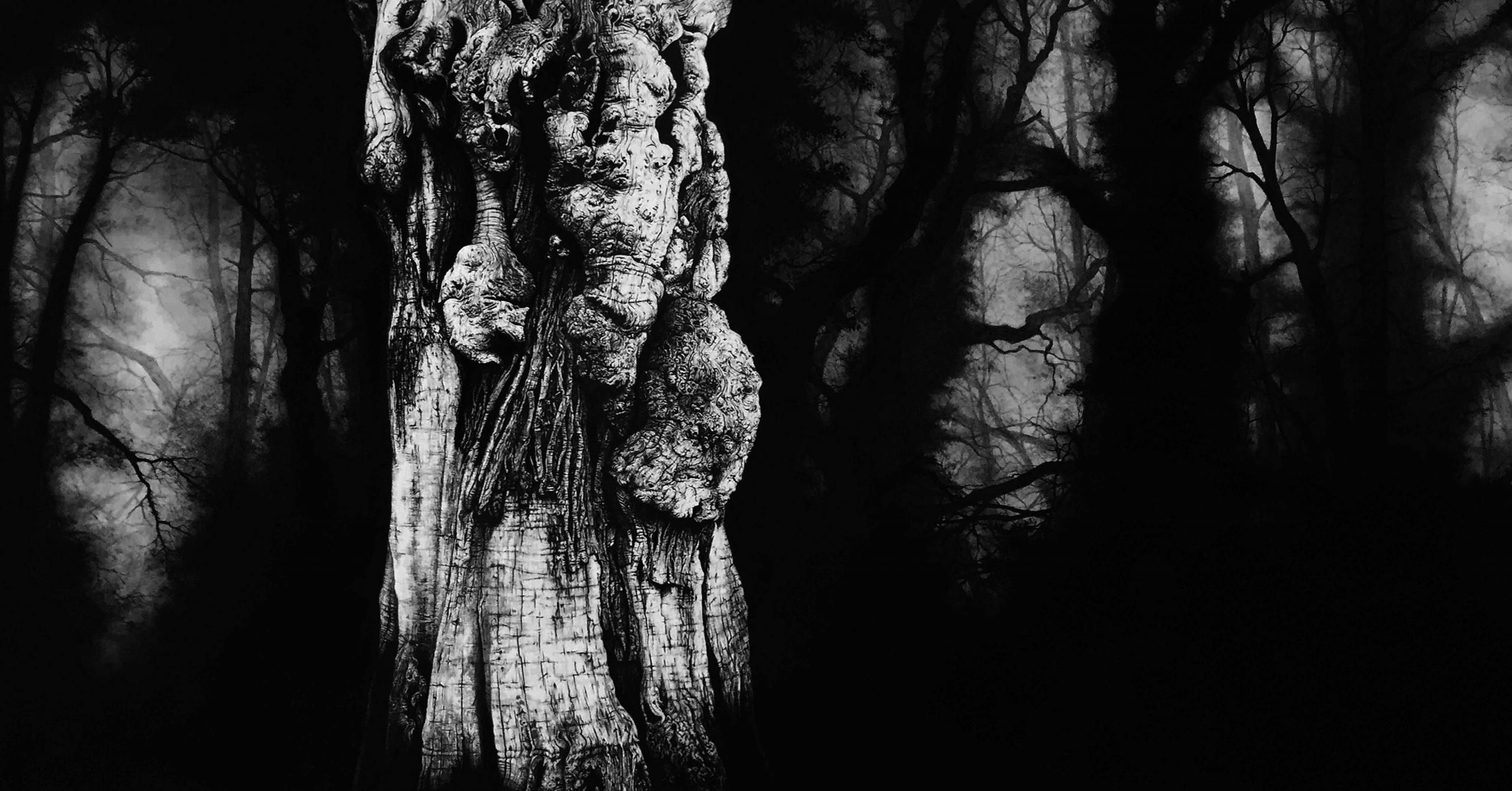

A View From A Hill — with its restless dead and its rupture of the pastoral — is, to my mind, a landmark text in a distinctive tradition of ‘eerie’ literature and art that has flourished in the shadows of British landscape culture, from the late 19th century through to the present day.

The eerie is, importantly, different both to the Gothic and to horror. For it involves that form of fear which is felt first as unease then as dread, and it tends to be incited by glimpses and tremors rather than outright attack. Horror specialises in confrontation and aggression; the eerie in intimation and intimidation. Its physical consequences are gradual and compound: a swarming in the stomach’s pit, the tell-tale prickle of the skin.

The etymology of the word itself is appropriately unclear. ‘Eerie’ materialises first in Middle English (eri, hery) to mean ‘fearful’, then gathers a specific sense of sourceless unease, malingering dread. The eerie is alarming because its cause can rarely be explained or even detected.

This sourcelessness also distinguishes the eerie from the horrific, and is also the reason that eerie art deals often in glimpses, tremors and forms of failed detection or observation. The eerie is monstrous precisely because it will not demonstrate itself (to demonstrate, from the Latin demonstrare, meaning to show or reveal).

Mark Fisher, in his 2017 book The Weird and the Eerie, notes also that the eerie displaces the human subject; it is concerned more with intrusion from the outside in — an external presence or agency that will not readily be accounted for by the usual conventions of perception or rationalisation.

Attempts to assimilate the eerie, or explain it away, will typically fail, not least because it is by definition hard to get a fix on the eerie ‘object’, which discloses itself, if at all, as aura, penumbra or atmosphere rather than as presence.

We might usefully oppose the ‘eerie’ tradition to that of the far better-known ‘pastoral’. ‘No shepherd, no pastoral,’ wrote Leo Marx succinctly in his 1964 book, The Machine in the Garden. Pastoral art idealises and idyllicises the rural world, usually for the delectation of urban audiences. It is, at its worst, a counterfeit culture static in manner and stagnant in politics: ‘enamelled’, to use Raymond Williams’s resonant term, which is to say paintedly fixed rather than dialectically inquisitive. Its covert function as a mode is to affirm existing orders of power.

As the great feminist geographer Doreen Massey puts it, the pastoral activates ‘landscape’s smoothing effect’, its ‘subtle operations of reconciliation’. The eerie, by contrast, refuses such smoothings. It rucks landscape up, cracks its surfaces, drills down into the uncanny forces, part-buried sufferings and contested ownerships that constitute it.

Landscape, in eerie art, is never a simple stage-set, there to offer picturesque consolations. Rather it is a realm that trips, bites and troubles. The eerie invokes the pastoral — that conservative green-dream of natural tranquillity and social order — only to traumatise it.

An eerie tradition runs through modern British landscape culture not as an overground river might — with a traceable and continuous surface route — but rather as groundwater moves; subtle, easy to overlook, but surging out unpredictably, especially at times of heavy weather.

Eerie art has often flourished at or after times of crisis, martial or fiscal: during the economic collapses of the 1970s and 2000s, for instance, or around and during the Second World War. There is little mystery to this pattern. For where the pastoral encodes order and succour, the eerie registers dissent and unease. It is drawn to what Christopher Neve memorably called ‘unquiet landscapes’ — and it is born of unquiet times. The supernatural and the paranormal have always been means of figuring anxieties and dissents that cannot otherwise find visible expression.

Extract from the exhibition catalogue for ‘Unsettling Landscapes: The Art of the Eerie’, at St Barbe Museum and Art Gallery, Lymington, Hampshire, until January 4, 2022 (01590 676969; www.stbarbe-museum.org.uk)

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.