The traditional British toy makers still crafting wooden tops, rocking-horses and teddy bears

From automata to wooden dogs with jointed legs, members of the British Toymakers Guild have crafted a cornucopia of intriguing playthings that are not only for children, says Claire Jackson.

The neat sweep of hair and strong jawline looks faintly familiar. Made in Switzerland in 1921, the metal doll is an early prototype for Action Man; his khaki-clad neighbours — one of whom uses a crutch — guard a sign saying ‘minefield’. Above them balances a large rocking horse; with its peeling paint and tired eyes, it is one of the older items in Pollock’s Toy Museum in London W1, known to have been sold in 1840. However, it is not the oldest piece in the London collection: there are wax dolls from the early 19th century and a clay mouse with a moving wooden mouth and tail dating from 2,000BC. Although there are some examples of toys that went on to be mass produced — such as Matchbox cars and Sooty puppets — the majority of those on display are handmade, detailing a long lineage of toy-making that still thrives today.

‘As well as the traditional toys — wooden tops, rocking-horses and teddy bears — there are makers who create more unusual things, such as Viking armour,’ notes David Plagerson, who, until recently, was chair of the British Toymakers Guild. The association has supported the craft since 1956, when the body was formed as a direct response to the rise of factory-made plastic toys — including Action Man and pals.

‘The Guild was initially based in the Wimbledon area, but has since spread across the country,’ explains Mr Plagerson. A catalogue of the guild’s historic collection is striking for its variety: from jigsaw puzzles to a rather alarming jack-in-the-box, everything is sewn, carved and painted with fizzing imagination, using the highest-quality materials.

These include Harris tweed, wool, felt and mohair fur fabric — the latter as used by German teddy-bear makers, Steiff. Alice Wood took inspiration from the plush toys to create Little Toy Dogs, collector’s pieces crafted with cotter-pin jointed legs made in the image of the commissioner’s own canine chums. She produces a small whippet and a fox terrier from her bag, both exquisitely crafted and filled with Romney Marsh wool. I gaze into the glass eyes of the whippet and instinctively stroke his head, adjusting the tiny collar.

‘I make miniature versions of the real dog’s clothes,’ reveals Miss Wood, showing me a photograph of her much-adored sheltie. My miniature dachshund shifts in the seat next to me. A toy in her likeness is deeply appealing. ‘These toys are generally for adults,’ notes Miss Wood. ‘To make them suitable for children, I have to use plastic pins rather than metal ones. There are all sorts of safety considerations. I don’t want my toys to catch fire — I want them to be able to sit on a chimneypiece.’

The clockwork clown and sailor doll in Enid Blyton’s Tales of Toyland never had to worry whether their outfits were flame-retardant, nor did Noddy fret over whether the bell on the end of his hat was sewn on tightly enough. Yet today’s toys must follow certain guidelines. ‘For example, the string on a pull-along toy can only be a certain length, so that a child cannot strangle their siblings; all the paints we use must be toy safe,’ cautions Mr Plagerson, who has represented the profession on several committees.

However, most of these restrictions can be circumvented if the toy is intended for adults. You don’t have to be Baron and Baroness Bomburst — the evil rulers of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang’s Vulgaria, who have captured the town’s toy maker — to enjoy toys as adults. (This is distinct from adult toys, which are very different.) Robert Race’s automata includes kinetic sculpture that is definitely not intended for children. ‘His work is glorious,’ enthuses Mr Plagerson. ‘I particularly love his 5ft skyscraper, which is cleverly weighted so that a King Kong can climb it.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

When Noddy first arrives in Toyland, he is put on trial to ascertain that he is actually a toy, rather than an ornament. In Toy Story, some five decades later, toys form a social hierarchy based on their popularity as playthings. However, in artistic terms, toys are simply ‘hand-held sculptural objects’, as Mr Plagerson neatly describes them. ‘I think it’s important to introduce children to aesthetic objects early on,’ he points out.

His own Noah’s Arks certainly do that: each hand-carved and hand-painted animal is delightfully tactile and beautifully made. At £1,785 for a collection with 12 pairs of creatures made from limewood, they are heirloom toys, built to last and pass through the generations. One of Mr Plagerson’s arks is part of the permanent display at the Bethnal Green Museum, the place that inspired him to engage with toy making when he was working as an art teacher in the East End of London.

There is a close relationship between toy making and the art world. As did Mr Plagerson, Miss Wood also comes from a creative background, having worked in illustration for many years, including for now-defunct Horse and Pony magazine. ‘During the [2008] financial crash, I lost three book contracts and all the work dried up. I saw it as an opportunity to refocus on making and joined the guild in 2016,’ she recalls.

One of Mr Plagerson’s prized toys in his own collection is a boat made by Sam Smith (1908–83), an accomplished toy maker and artist whose work straddles the serious and the silly. Another British artist who has been inspired by toys is Sir Peter Blake, the collage specialist famous for his work on the cover of The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The 1999 exhibition at London’s Morley Gallery, ‘A Cabinet of Curiosities’, showcased Blake’s own collection, with toy elephants, model Elvis dolls and vintage Punch and Judy puppets — a passion that had fuelled 1962 installation The Toy Shop, now owned by Tate. The reverence attached to these objects is at odds with their broader treatment. ‘Toy-making has a poor reputation,’ reflects Mr Plagerson. ‘We talk of “toying” with emotions; it’s a pejorative word. Toys today are disposable.’

The windows of Hamleys on London’s Regent Street are filled with LOL dolls — big-eyed, heavily made-up miniature women with accessories for fashion shows and cheerleading. The other window displays the latest Lego range: Andrea’s Theatre School and Mia’s Wildlife Rescue. The plastic zebra and giraffe are sweet enough, but the LOL OMG Spicy Babe Fashion Doll has a shelf life shorter than you can say ‘landfill’. Back at Pollock’s shop on Scala Street, there are more enticing options: paper toy theatres reproduced from archive designs, poly- styrene aeroplanes and board games.

Happily, traditional toy making recently received a boost from an unlikely source — Disney’s live-action remake of 1940 animation Pinocchio featured the famous puppet and other toys, for which several members of the guild provided set materials. Perhaps Tom Hanks, who plays toy maker Geppetto in the film, will receive honorary membership.

See more about the British Toymakers Guild at www.toymakersguild.co.uk

Christmas gifts for children that don't need screens or take batteries

Don't just pick up the latest plastic toys with lights and noises – take a look at these gifts which kids

Credit: Christmas Gift Guide 2023 — Image supplied by maker

Christmas gift ideas for ladies

From mothers and sisters to wives and girlfriends, these 12 gifts are sure to bring a smile to the face

Christmas gift ideas for men

From fathers to brothers to lovers, we run through some smart ideas for Christmas presents for the men in your

-

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotels

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotelsWhen it comes to hotel design, the Brits do it best, says Giles Kime.

By Giles Kime Published

-

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication'The Great Gatsby' sold poorly the year it was published, but, in the following century, it went on to become a cornerstone of world literature.

By Carla Passino Published

-

Christmas gift ideas for children

Christmas gift ideas for childrenFrom adorable booties and cardigans to toys that will keep tiny tots entertained for hours.

By Hetty Lintell Published

-

Seven perfect Christmas gifts for people who just love beautiful, functional things

Seven perfect Christmas gifts for people who just love beautiful, functional thingsWilliam Morris famously said to have nothing in your house that you don't know to be useful or believe to be beautiful. These things do their best to hit both targets.

By Toby Keel Published

-

Christmas gift ideas for ladies

Christmas gift ideas for ladiesFrom mothers and sisters to wives and girlfriends, these gifts are sure to bring a smile to the face of the special lady in your life.

By Country Life Published

-

Christmas gift ideas for men

Christmas gift ideas for menFrom fathers to brothers to lovers, we run through some smart ideas for Christmas presents for the men in your life.

By Country Life Published

-

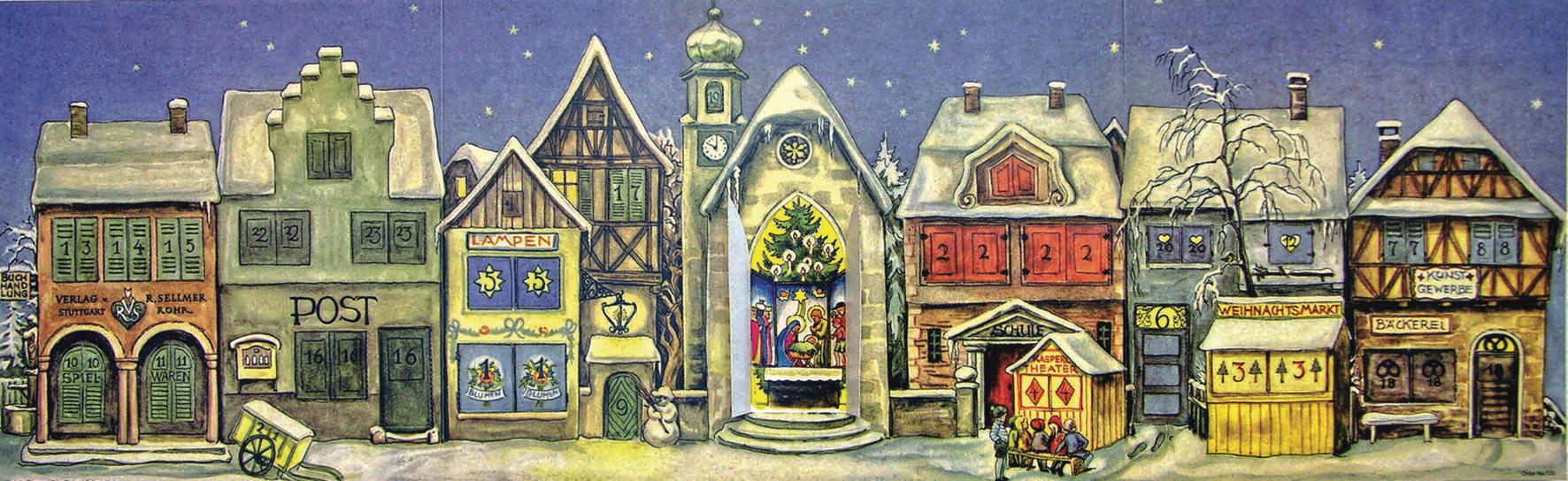

The five most beautiful Advent Calendars of Christmas

The five most beautiful Advent Calendars of ChristmasThe best Advent calendars of 2024, as chosen by Flora Watkins.

By Flora Watkins Published

-

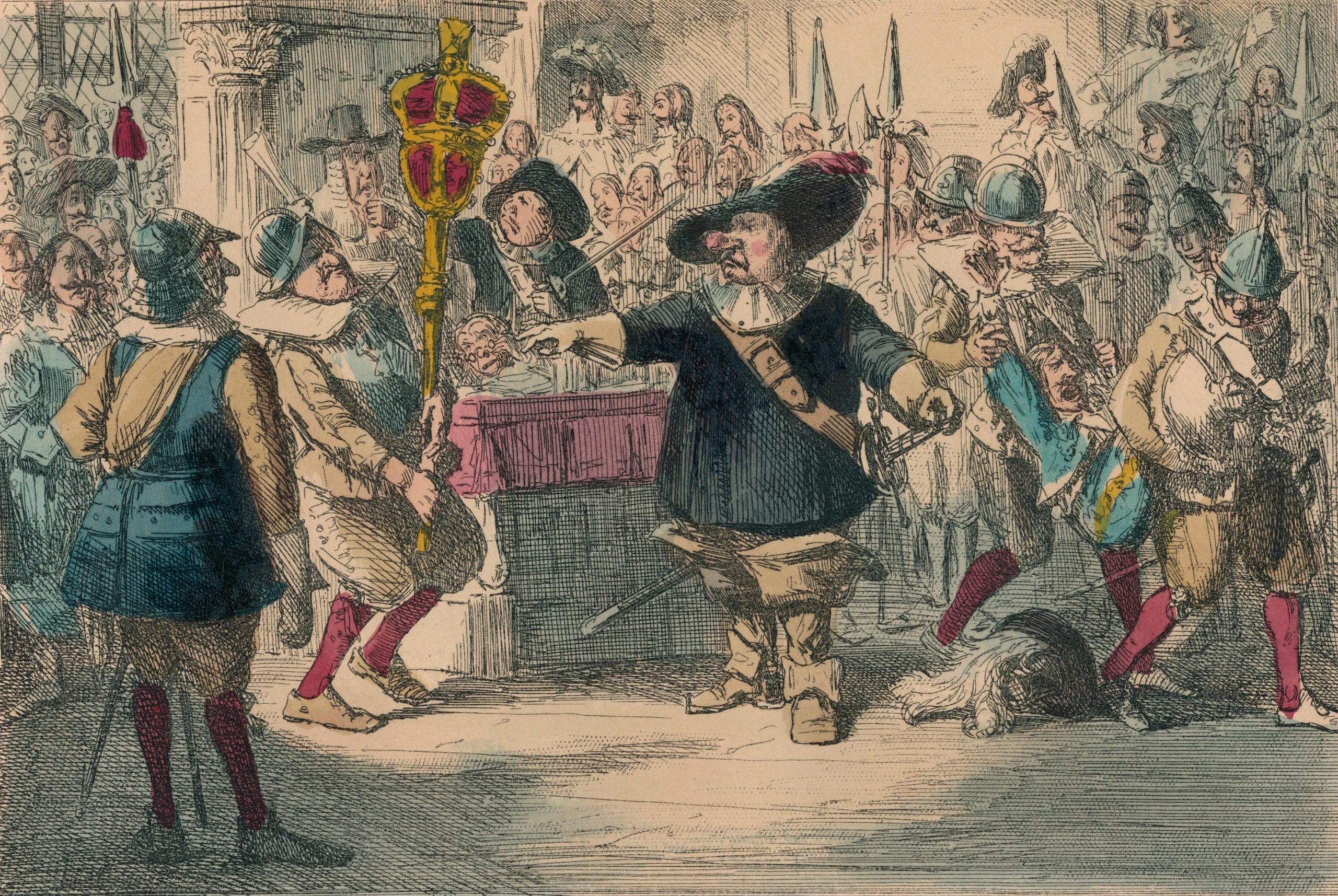

When England cancelled Christmas

When England cancelled ChristmasNo feasting. No drinking. No celebrations. Ian Morton explores what the festive period was like when Oliver Cromwell’s Christmas clampdown gripped the nation.

By Ian Morton Published

-

11 ways to do Christmas in right royal style, by A-list party planner Johnny Roxburgh

11 ways to do Christmas in right royal style, by A-list party planner Johnny RoxburghJohnny Roxburgh, one of Britain's top party planners, shares his tips on the best things to have at your own seasonal celebrations.

By Johnny Roxburgh Published

-

Christmas gifts for children that don't need screens or take batteries

Christmas gifts for children that don't need screens or take batteriesDon't just pick up the latest plastic toys with lights and noises – take a look at these gifts which kids will love just as much as you do.

By Country Life Published