In Focus: John Hassall's iconic travel posters

The works of British poster king John Hassall remain a breath of fresh seaside air, says Lucinda Gosling.

Utter the word ‘Skegness’ and many people will find it hard to resist interjecting, ‘is SO bracing’. It’s one of the most well-known slogans from one of the most famous travel posters of all time.

In May 1908, when the artist John Hassall recorded the receipt of 12 guineas in his ledger for a design of a ‘Fisherman dancing’, he can’t have predicted that this particular commission, one of thousands carried out in his lifetime, would become his visual epitaph, nor that, more than 110 years later, his poster would still be an inspiring template for today’s cartoonists and illustrators.

The Jolly Fisherman, prancing with balletic grace across the sand, his round belly inflated with invigorating sea air and his arms outstretched in carefree abandon, has become synonymous not only with the Lincolnshire seaside resort, but with a cheery, stoic brand of Britishness — a tendency to make the best of things in a country at the mercy of unpredictable weather.

He eschews the sunshine and genteel atmosphere of southern resorts such as Torquay in favour of something more vigorous to blow the cobwebs away. Skegness could boast neither a mild climate nor fashionable spa hotels, so it was pleased to have ‘Jolly’ as its champion, finding the good in the winds rolling in from the North Sea. The poster was revised and reworked several times through the decades (Hassall added the pier in a 1926 version) and Jolly remains an instantly recognisable symbol of the town today.

Hassall’s image, a perfect partner to the slogan provided by Great Northern Railway, boiled the resort down to three key elements: sea, sand and that bracing fresh air. There were no landmarks to indicate what Skegness might actually look like.

Instead, it was Jolly, with a bloom in his cheeks and a twinkle in his eye, who summed up the spirit of the place. Hassall served up a sequel in 1911, carried out in his typical bouncy, boisterous style — this time Skeggy’s therapeutic breeze had breathed new life into an invalid, causing him to spring out of his bath chair and pull it along the seafront.

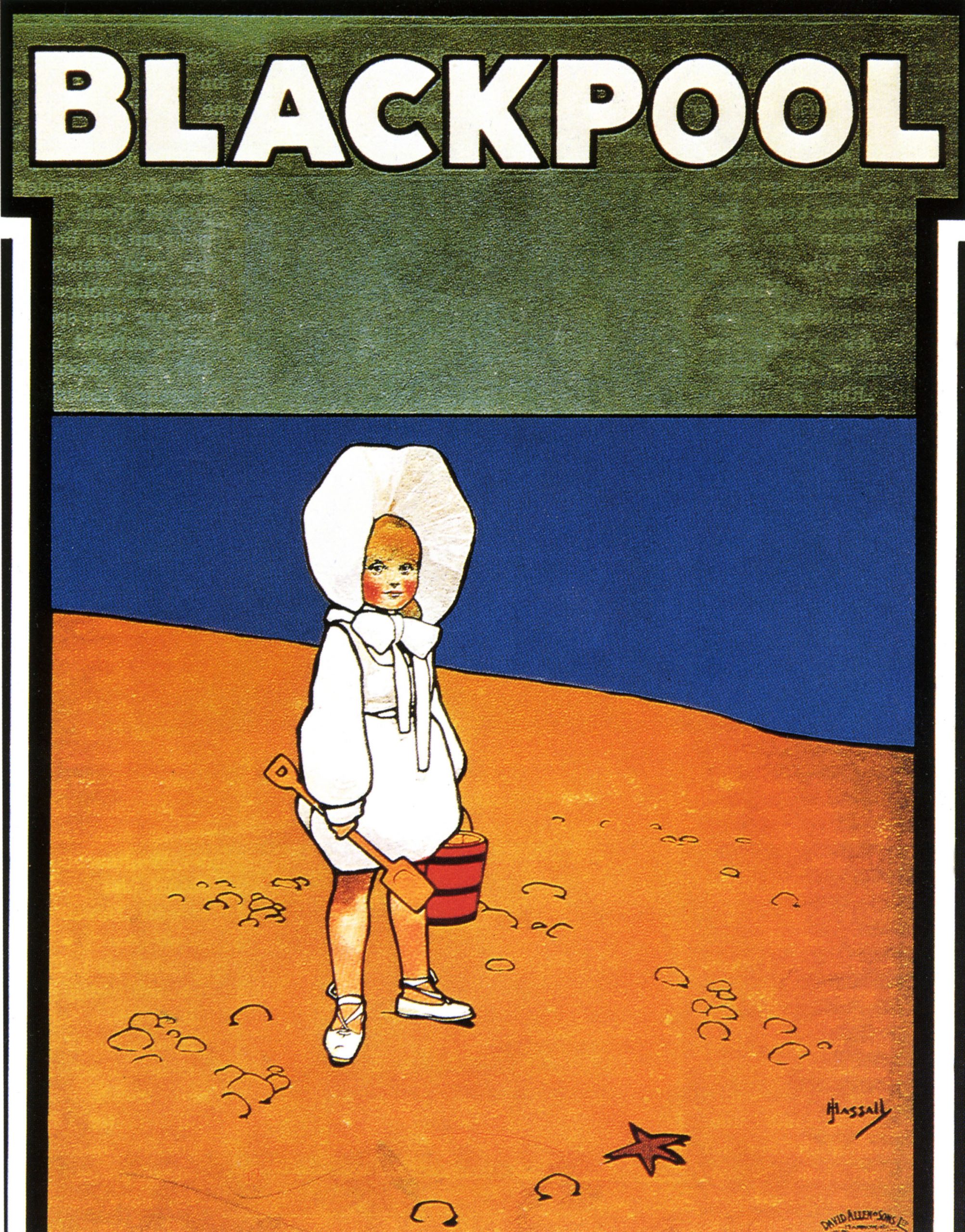

A little earlier, in 1907, the illustrator’s poster for Blackpool depicted one small girl on a deserted beach — no slogan, no visible amusements. It was pleasingly simple and surprisingly effective, a world away from the gaudy and faintly disreputable Blackpool we know and love.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Although the development of resorts was still not extensive at the time Hassall was designing these posters, to show them without any hint of the amusements on offer was a gamble. What he created was a memorable graphic statement evoking a coastal idyll. Even if it was nowhere near a reflection of reality, it somehow worked.

"The Jolly Fisherman became synonymous with a cheery, stoic brand of Britishness"

His poster for Morecambe in 1907, of a boy in red playing in the sand, followed the same formula — sea, sand, blue sky, a hint of sunshine and not a Pierrot troupe, ice-cream seller or raucous day tripper in sight.

Hassall was born by the sea in 1868, in Walmer, close to Deal in Kent. His route to becoming an artist was circuitous. Intended for the army, he managed to fail the entrance examinations for Sandhurst, causing him to board a ship to Canada with his younger brother to try his luck as a pioneer farmer in Manitoba province.

Hassall proved himself resourceful and hard-working, but discovered that he had a talent for drawing after winning prizes at a local art exhibition and then sending off a picture of Canadian life to the Daily Graphic in London — it was published in the issue of February 26, 1890.

He decided to leave Canada behind and enrolled at art school in Antwerp, also spending six months studying at the prestigious Academie Julian in Paris.

By 1894, Hassall was married and had set up home and studio at 88, Kensington Park Road in Notting Hill. In the same year, he had two paintings accepted for exhibition at the Royal Academy, but earned his bread and butter by drawing for illustrated magazines such as Tit-Bits, The Graphic, Moonshine and, in particular, The Sketch.

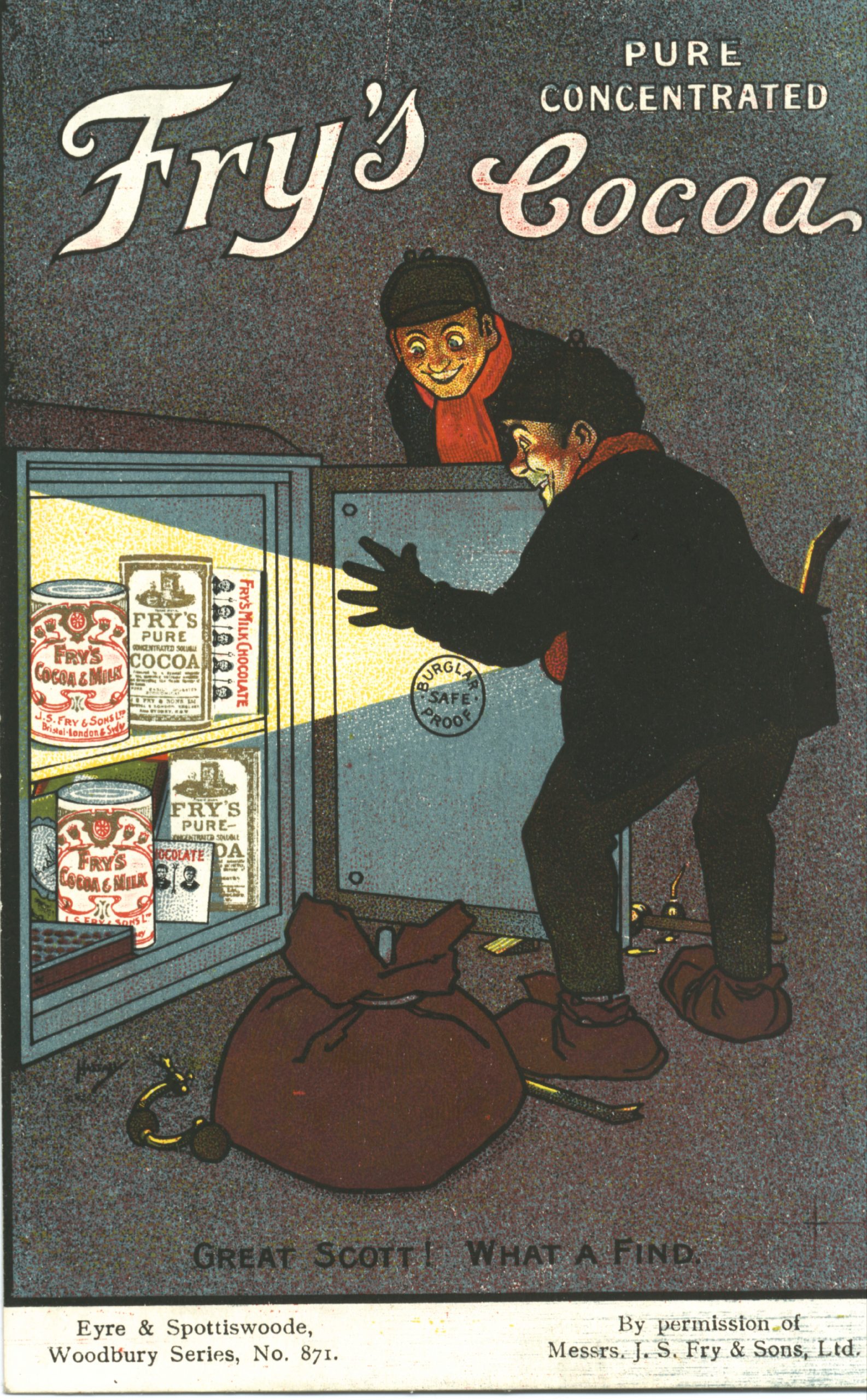

In December 1895, an introduction to David Allen & Sons, the leading printer of theatrical posters, was the catalyst for his meteoric rise to fame. Demonstrating a natural affinity for poster design, over the next four years, Hassall produced close to 600 posters for the firm, many for the theatre, but also for grocery and household brands such as Colman’s Mustard and Fry’s Cocoa.

His timing could not have been better. During the 1890s, a new type of artistic poster was taking Europe and the US by storm, turning the advertising hoardings of towns and cities into what was dubbed ‘the poor man’s picture gallery’ and whipping up a ‘poster-mania’ that saw a craze for collecting among connoisseurs.

Initially influenced by the great poster artists of Paris, such as Jules Chéret, Toulouse-Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha, Hassall soon established his place within a British school of poster artists alongside the likes of Dudley Hardy, Tom Browne, Cecil Aldin and the Beggarstaff Brothers.

"Artistic posters were taking Europe and the US by storm, turning hoardings into the poor man’s picture gallery"

All used flat, contrasting colours drawn from a limited palette, bold outlines, minimal lettering and eye-catching simplicity.

The popularity and influence of Japanese art at the time encouraged poster artists to experiment with negative space and this restraint in composition, combined with punchy colour schemes, led to posters that made an impact from a distance and could stand out in dirty, smog-filled cities or through the smoke of railway stations. These were all hallmarks of the classic Hassall poster, but he also had an instinctive ability to tickle the Edwardian public’s sense of humour and appeal to the man or woman on the street.

Posters — particularly Hassall’s posters — became an intrinsic part of popular culture. The best examples provoked conversation, were discussed in the press and were sometimes brought to life on stage.

Some were reimagined as political cartoons or as comments on current events. In 1914, soon after the German bombardment of Scarborough and Hartlepool, The Tatler published a cartoon by James Thorpe showing the Jolly Fisherman dodging shells on a beach, with the punchline ‘The East coast is so bracing’.

By the early 1900s, Hassall was frequently hailed ‘the king of poster artists’. Considering his prolific output, his works for British seaside resorts are comparatively few, although it is worth remembering that his heyday preceded the inter-war golden age of the railway poster by more than 20 years.

Yet his Skegness design was trailblazing, ‘a masterpiece which started a new vogue in railway advertising’, according to the passenger manager of the London and North Eastern Railway when paying tribute to Hassall in the 1930s.

The seaside featured frequently in his humorous drawings for magazines and the many children’s picture books he illustrated, such as Our Diary: or Teddy and Me (1905), which features children in a boat with a rotund fisherman.

This blueprint for Jolly can also be found in an earlier book of 1902, The Round the World ABC, where a suspiciously familiar-looking sailor appears under ‘P for Penzance’. Hassall’s immense workload meant he often recycled ideas and many illustrations seem to mirror his own family life.

"His Skegness design was trailblazing, a masterpiece which started a new vogue"

Each year, the Hassall family would enjoy a British seaside holiday. His first wife, Isabella, had died in childbirth in 1900, leaving him a widower with three young children under four, Dorothy, Ian and Isabel.

In 1903, he remarried and, with his new wife, Maud, had two more children: Joan, who became a successful artist and wood-engraver, and Christopher, the poet, biographer and lyricist. They holidayed at Runton in Norfolk, at Worthing in West Sussex and at Walton-on-the-Naze, Essex.

The latter became Hassall’s second home following their first holiday there in 1908; in the 1920s, he designed a poster for the town, of a little girl in a large bonnet on the beach. He could easily have been depicting one of his own daughters. Equally, the boy in Hassall’s 1907 Morecambe poster bears a striking resemblance to his son Ian.

In 1936, Hassall was invited to Skegness for the very first time by the Skegness Advancement Association. He kept the assembled dignitaries waiting after mistakenly going to Liverpool Street rather than King’s Cross to catch his train, an error made all the more amusing by the fact that his 1908 poster had included a timetable.

Arriving on a later train, he was given a tour of the town and a dinner was held in his honour, after which he was presented with an illustrated vellum in recognition of all he had done to put Skegness on the map. When he died in 1948, Skegness Council sent a wreath with the Jolly Fisherman picked out in flowers. In death, as in life, the Jolly Fisherman of Skegness accompanied Hassall everywhere.

‘John Hassall: The Life and Art of the Poster King’ by Lucinda Gosling is published by Unicorn Publishing. ‘John Hassall: Illustrator and Poster Artist’ is at the Heath Robinson Museum, Pinner, Greater London, until August 29

Other coastal artists

Donald McGill (1875 –1962) If John Hassall was king of poster artists, then Donald McGill was undoubtedly king of the saucy seaside postcard. Producing somewhere close to 12,000 postcard illustrations during his lifetime, of which 200 million copies were printed, McGill’s cheeky designs (such as his take on the Jolly Fisherman) became synonymous with kiss-me-quick, British seaside humour.

Dame Laura Knight (1877–1970) The first woman to be elected to the Royal Academy, Laura Knight honed her craft in the artistic colonies of Staithes in North Yorkshire and Newlyn in Cornwall. Committed to paint- ing en plein air and recording the rural lives of ordinary people, Knight’s paintings of Larmona Cove and Sennen Cove capture the wild drama and natural beauty of the Cornish coast (as in On the Cliffs, above).

David Cox (1783–1859) In the 1840s, David Cox began to regularly visit Wales and, at the seaside town of Rhyl, painted numerous scenes in watercolour and oils (such as Rhyl Sands, above). His impressionistic landscapes pay homage to big skies and wide, open beaches, but his inclusion of numerous figures strolling or playing on the sand give an insight into the seaside of the early-Victorian era, when the railways were opening up new destinations, but towns were still undeveloped.

William Powell Frith (1819 –1909) William Frith was more interested in painting modern life than landscapes, but his first big success, Life at the Seaside (Ramsgate Sands) (top) exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1854, is one of the greatest of British seaside paintings. Teeming with detail and activity, the painting was eventually bought by Queen Victoria, who had fond memories of visiting Ramsgate with her mother between 1825 and 1836.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to last

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to lastKitchen and joinery specialist Artichoke had several clever tricks to deal with the fact that natural wood expands and contracts.

By Amelia Thorpe

-

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025Friday's quiz is an Easter special.

By James Fisher

-

In Focus: How the 'Tottering Hall' cartoonist became a sculptor

In Focus: How the 'Tottering Hall' cartoonist became a sculptorBest known as the creative force behind Dicky and Daffy, it was her son’s death that prompted Annie Tempest to learn ‘the grammar of the sculptor’s language’, discovers Ian Collins.

By Country Life

-

In Focus: How Italy inspired JMW Turner

In Focus: How Italy inspired JMW TurnerMary Miers considers how the country that fascinated Turner from youth shaped his artistic vision.

By Mary Miers

-

In Focus: Why the eerie thrives in art and culture

In Focus: Why the eerie thrives in art and cultureThe tradition of ‘eerie’ literature and art, invoking fear, unease and dread, has flourished in the shadows of British landscape culture for centuries, says Robert Macfarlane.

By Country Life

-

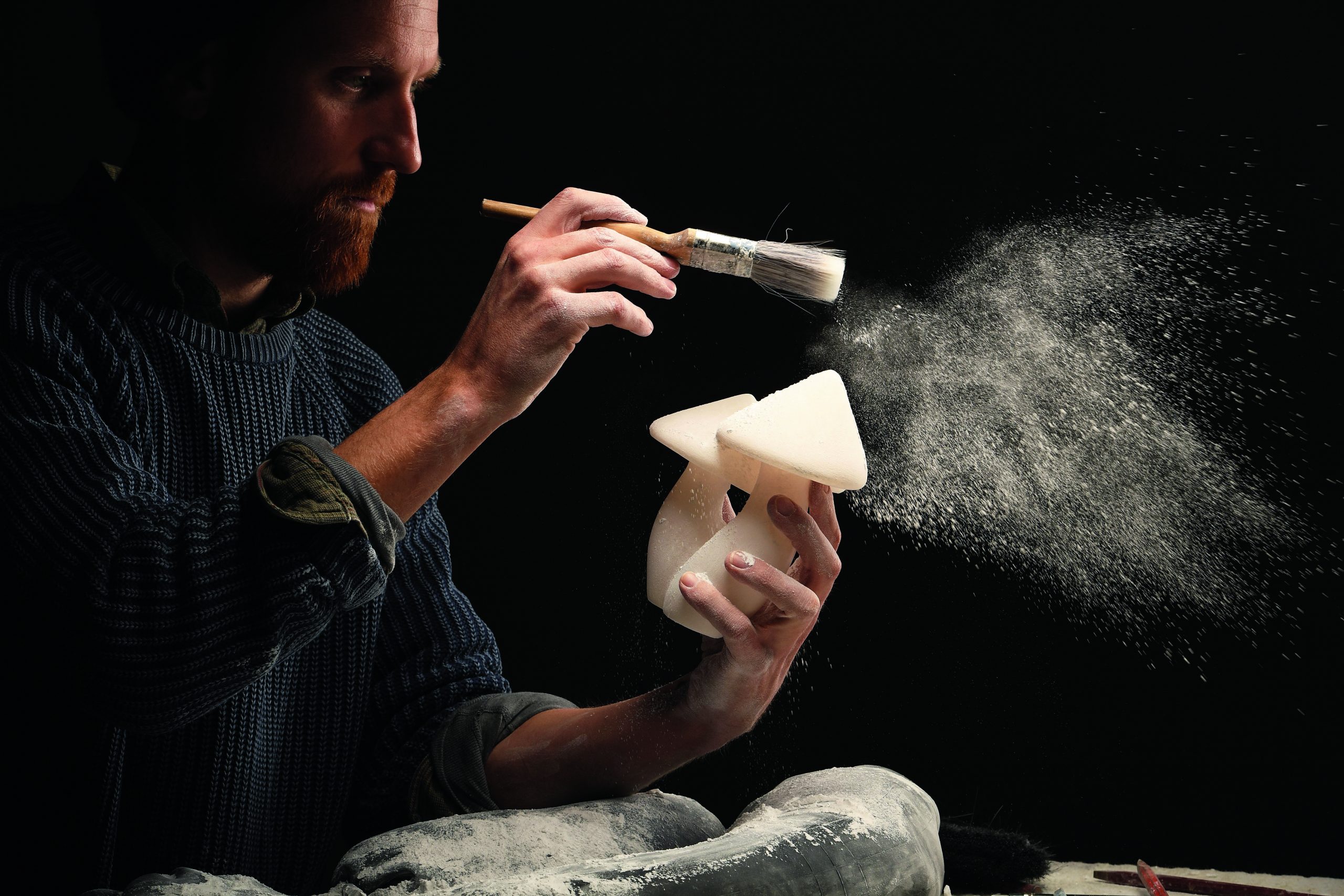

In Focus: the fungi sculptures that bend stone into soft, flowing forms

In Focus: the fungi sculptures that bend stone into soft, flowing formsThey may look as delicate and organic as the real thing, but Ben Russell’s sculptures of fungi, cacti and roots will outlast us all, believes Natasha Goodfellow.

By Country Life

-

In Focus: How 21st century artists are reviving the art of the fresco

In Focus: How 21st century artists are reviving the art of the frescoOnce practised by Michelangelo, Raphael and da Vinci, the art of fresco creation has changed little in 1,000 years. Marsha O’Mahony meets the artists following in their footsteps.

By Country Life

-

Why a good frame can be a work of art in its own right

Why a good frame can be a work of art in its own rightCatriona Gray retraces the history of frames, admires the craftsmanship required to make them and discovers what's the best way to preserve them.

By Country Life

-

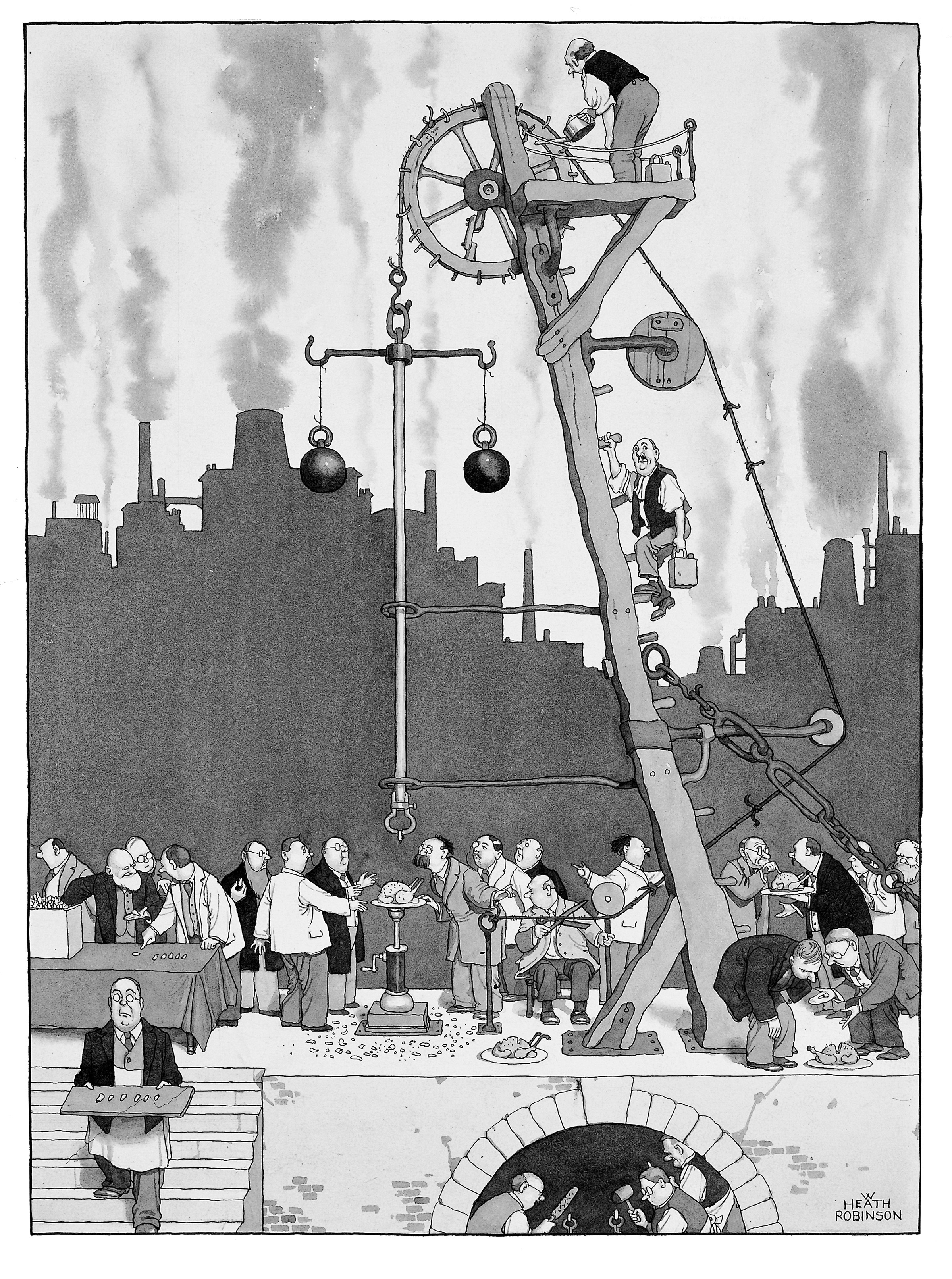

In Focus: The Heath Robinson Museum at Pinner, home to decades of gently satirised modern life

In Focus: The Heath Robinson Museum at Pinner, home to decades of gently satirised modern lifeHuon Mallalieu tells the story of the small museum in Middlesex, where you'll find the last records of the county before it became overrun by suburbia.

By Huon Mallalieu

-

In Focus: How British artists contributed to the uncanny, desirous world of Surrealism

In Focus: How British artists contributed to the uncanny, desirous world of SurrealismMichael Murray-Fennell delves into the subconscious, the uncanny, war and desire and discovers the contribution made by British artists to the Surrealist movement.

By Country Life