Meet the man who builds his own Tiger Moths: Grace, glamour, romance – and hours of painstaking hard work

The Tiger Moth is the iconic biplane in which almost every British pilot was trained during the Second World War. Mark Palmer meets the man resurrecting these elegant old ladies of the sky, with photographs by Mark Williamson.

In 1954, shortly before his 15th birthday, Kevin Crumplin made a model of a Tiger Moth. It comprised a balsawood fuselage, a 3ft wingspan and a small diesel engine that helped propel it through the sky.

Friends were impressed, but it wasn’t entirely his own work. Kevin’s father worked in the mining industry in the family’s native South Africa and help was always available from the enthusiastic German engineers working at the mine.

They proved useful when it came to assembling the various parts of the kit and making sure it got off the ground, albeit in a non-controlled fashion. Drones were a long way down the runway at that time.

‘I had read Biggles as a child and found the whole flying world, especially biplanes, so exciting,’ says Kevin.

‘Tiger Moths were the nearest I could get to that feeling of adventure and daring.’

Speed forward 60 years and Kevin slides open the doors of his rented hangar at Henstridge Airfield near Milborne Port, Somerset, to reveal four Tiger Moths he’s restored – not assembled from kits, not schoolboy models, but the real thing, primed and ready to soar into the sky. They epitomise grace, glamour and romance, but they’re also evidence of painstaking work and an all-consuming passion for the planes that played a crucial part in defending Britain during the Second World War.

‘To describe Tiger Moths as iconic is an understatement,’ believes Kevin.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

‘They were known as “the Trainer of the Empire” because almost every British and Allied wartime fighter pilot learnt to fly in them. The fact that some are still flying is remarkable.’

What’s just as remarkable is that this softly spoken man approaching his 80th birthday is widely considered to be the leading authority on Tiger Moths and the expert’s expert when it comes to restoring them.

‘It’s a hobby not a business and it gives me immense satisfaction,’ explains the man whose wife of more than 50 years waves him off up to six days a week as he heads for Henstridge.

It’s an expensive hobby. You can buy a non-airworthy Tiger Moth in various states of disrepair for anything between £10,000 and £20,000. Then, according to Kevin, expect to pay a further £30,000–£50,000 on parts and putting it all together.

Usually, it takes him 12 months to restore a plane, but, increasingly, he’s in the habit of working on two at a time. ‘Part of the challenge is finding the parts. I go on eBay and sometimes see things at car-boot sales, but every restored section of the plane has to be inspected and all replacement parts need a Certificate of Conformity from the Civil Aviation Authority.’

From time to time, Kevin will sell one of his restored planes to recoup his costs. A year ago, he had an enquiry from a man called Richard Santus from the Czech Republic, who was keen to buy one and did so after one viewing.

To add an extra element of daring, he then set about flying the Tiger Moth all the way home – in January, with temperatures on the ground alone at just below freezing.

Taking off and landing at a variety of civilian airfields (flying at 3,000ft in between), he eventually touched down at Podhorany near Cesko three days later.

At Henstridge, Kevin has joined forces with two experienced flying instructors, Clive Davidson and Annabelle Burroughes, to set up Tiger Moth Training. They charge £250 an hour for training flights and £400 an hour (£200 for 30 minutes) for pleasure flights. Included in any flight is a chance to look around Kevin’s hangar and learn first-hand about Tiger Moths and their construction.

These biplanes are remarkably light and can be wheeled out onto the grass as if guiding a lawnmower. There are no brakes or tailwheel because that would add weight and flying requires someone on the ground to swing the propeller to start the engine.

Take-off speed is less than 65mph and a mere 100 yards are needed before a Tiger Moth reaches for the skies. Coming into land – as long as there’s no strong crosswind – is gentle and the plane simply slows to a halt of its own accord.

Kevin was born near Johannesburg in 1939 and came to Britain aged 20, eventually joining the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm, where he did his initial pilot grading in Tiger Moths. Unfortunately, he had a bad accident during an expedition on the River Ure and was unable to complete his flying training. Instead, he became a Sea Vixen fighter-aircraft observer, based mainly on aircraft carriers, and progressed to be an observer instructor at RNAS Yeovilton, Somerset. In later years, he pursued a career in personnel, ultimately at shoe company Clarks, where he ended up a member of the board.

Traditional retirement, Kevin claims, isn’t something that interests him, especially now that he’s bought a Gipsy Moth and has set about rebuilding it. Gipsy Moths preceded Tiger Moths and his is a 1930 model almost identical to the one that starred with Robert Redford and Meryl Streep in Out of Africa.

https://youtu.be/7MEY0dvV4hE?t=5s

So what will he do with the Gipsy Moth once he’s finished bringing it back to life? ‘Good question. These planes become like children and I would hate to let it go. The first thing I will do is fly it. I’ve never flown a Gipsy Moth, so it will be an exciting moment,’ he smiles.

‘Then, I’ll take others up in it. We have families coming to us that want to give one of their grandparents a special birthday or anniversary present. What I love is seeing the look on their faces at the end of the flight – it makes it all worthwhile.’

Find out more about Tiger Moth Training in Somerset at www.tigermothtraining.co.uk

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old Masters

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old MastersThe younger generations’ appetite for everything vintage bodes well for the future, says Huon Mallalieu, at a time when an extraordinary Old Masters collection is about to go under the hammer.

By Huon Mallalieu

-

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comeback

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comebackThe Kentish glory moth has been absent from England and Wales for around 50 years.

By Jack Watkins

-

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old Masters

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old MastersThe younger generations’ appetite for everything vintage bodes well for the future, says Huon Mallalieu, at a time when an extraordinary Old Masters collection is about to go under the hammer.

By Huon Mallalieu

-

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication'The Great Gatsby' sold poorly the year it was published, but, in the following century, it went on to become a cornerstone of world literature.

By Carla Passino

-

Shark tanks, crocodile lagoons, laser defences, and a subterranean shooting gallery — nothing is impossible when making the ultimate garage

Shark tanks, crocodile lagoons, laser defences, and a subterranean shooting gallery — nothing is impossible when making the ultimate garageTo collectors, cars are more than just transport — they are works of art. And the buildings used to store them are starting to resemble galleries.

By Adam Hay-Nicholls

-

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of spring

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of springThe biggest-ever David Hockney show has opened inside the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris — in time for the season that the artist has become synonymous with.

By Amy Serafin

-

Under the hammer: A pair of Van Cleef & Arpels earrings with an intriguing connection to Princess Grace of Monaco

Under the hammer: A pair of Van Cleef & Arpels earrings with an intriguing connection to Princess Grace of MonacoA pair of platinum, pearl and diamond earrings of the same design, maker and period as those commissioned for Grace Kelly’s wedding head to auction.

By Rosie Paterson

-

Why LOEWE decided to reimagine the teapot, 25 great designs over

Why LOEWE decided to reimagine the teapot, 25 great designs overLoewe has commissioned 25 world-leading artists to design a teapot, in time for Salone del Mobile.

By Amie Elizabeth White

-

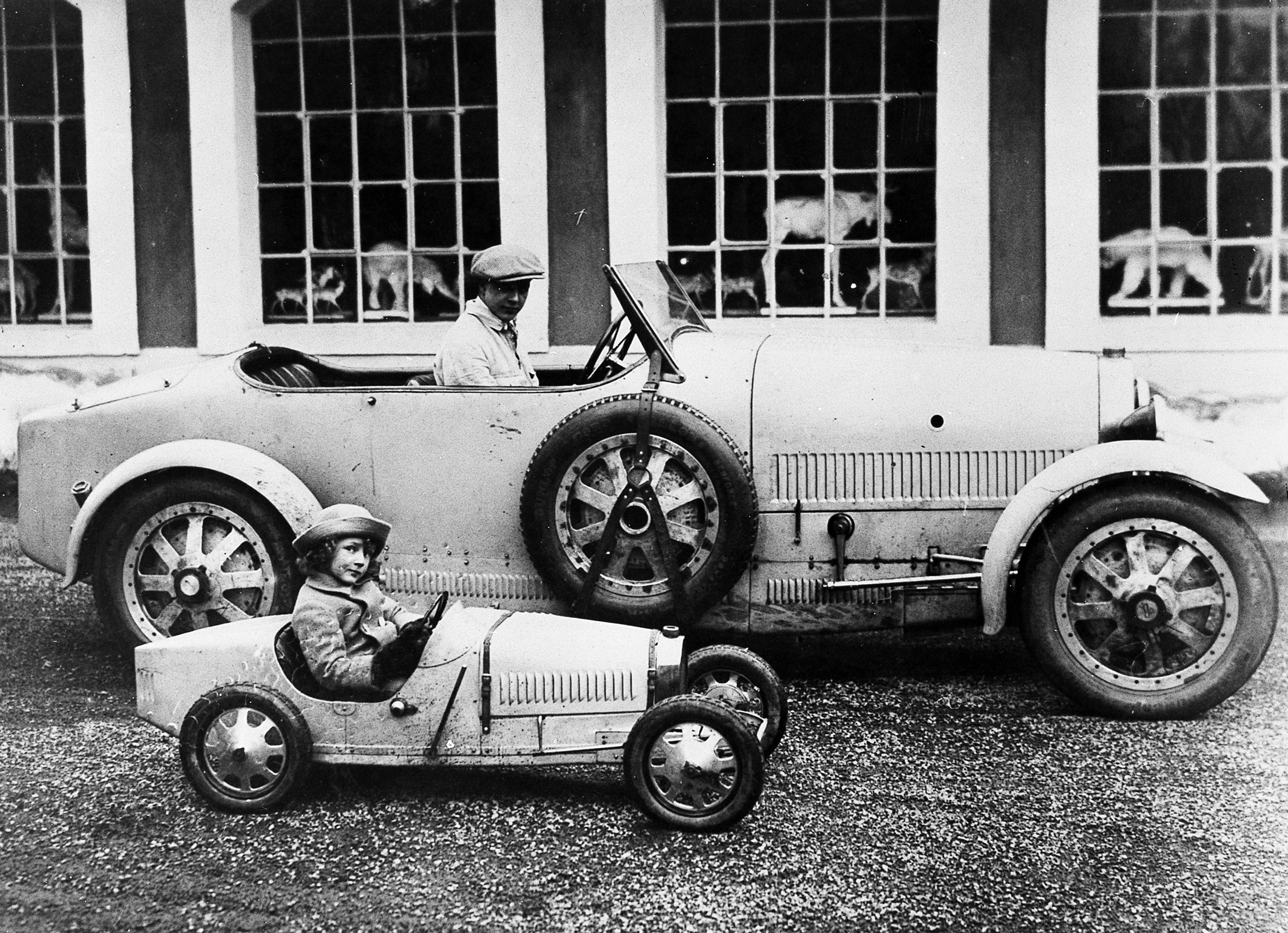

The brilliant Bugattis: Sculpture, silverware, furniture and the fastest cars in the world

The brilliant Bugattis: Sculpture, silverware, furniture and the fastest cars in the worldA new exhibition at this year's Treasure House Fair will shine a light on the many talents of the Bugatti dynasty.

By James Fisher

-

Big, bright and bold: Colourful luggage to inspire your next spring getaway

Big, bright and bold: Colourful luggage to inspire your next spring getawayIf RIMOWA's new 'Holiday' campaign is anything to go by, then conservative-coloured luggage is out and eye-catching is in.

By Rosie Paterson