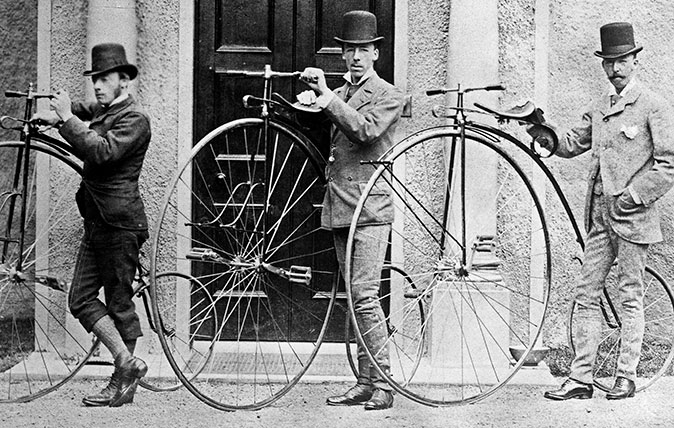

The penny-farthing rider who made a 400-mile trek across war-torn Ukraine

Is it still possible to use a penny-farthing today? The answer is an emphatic yes, at least if you're former Special Forces officer and adventurer Neil Laughton. He rode his Victorian high wheeler for 400 miles across war-torn Ukraine, doing everything from making pizza for local children to raising money for charity. Here he tells his tale.

I dismounted from my penny-farthing in the heart of Makariv, a provincial Ukrainian town 35 miles west of the capital, Kyiv, and walked into a restaurant called Vasabi. It was deserted except for a group of 10 young women, who were sitting around a rectangular table crammed full of local dishes and bottles of Ukrainian vodka. There was a palpable silence as my unexpected presence on a Sunday afternoon was digested. I doffed my black top hat, leant my 54in-diameter-wheeled bicycle against the wall and blurted out: ‘Excuse me for interrupting, but I’m British. Nice to meet you.’ I had stumbled into Lena’s private birthday celebrations.

Shortly afterwards, having been joined by my expedition colleagues Paula Reid and Mark Cropley, we exchanged greetings and I explained that we were midway through a 400-mile charity cycle challenge from the southern city of Odessa to the most northern town on the border with Belarus, Chernobyl. Recovering from the shock of some foreigners gatecrashing their party, a couple of the English-speakers began firing questions while making room for us at their table. It wasn’t long before we had downed three shot glasses brimming with home-made vodka.

Last year, from late February to the end of March, the town of Makariv was subject to the full horrors of the Russian military invasion. The 37th Motor Rifle Brigade entered the town from the north with tanks, armoured personnel carriers and self-propelled artillery with missiles and flame throwers. They came up against severe resistance from the Ukrainian defence forces, but at great sacrifice by the civilian population.

Yuliia showed me a video on her mobile phone. It depicted two young girls in white floral dresses skipping, dancing and playing in and around the town before February 24, 2022. One of the girls carries a toy white rabbit. The scene changes to apocalyptic devastation, as the same girls — now dressed in black dresses — navigate their way around the smoking embers of their town. She goes on tearfully to explain that her friend, a teacher in the town, was brutally raped and murdered by a Russian soldier. We are interrupted by Anastasia: ‘We’ve had Covid, then war with Russia. My friends and I just want a peaceful life, to work and to have fun.’ It was heart-breaking to hear these first-hand accounts of the terror of an invading army that has shattered their lives and livelihoods.

For my part, a semi-retired entrepreneur and experienced adventurer, I had been leading a winter expedition to Lake Baikal, Siberia, during the first weeks of the invasion. After extracting my team from Russia via Dubai in mid-March 2022, we volunteered to join and re-supply the advance party of a charity called Siobhan’s Trust, led by my great friend David Fox-Pitt at Medyka on the Polish/Ukrainian border. We volunteered to help run a 24-hour aid station, dishing out blankets and pizza to families fleeing the conflict. At night, when the border guards were less busy, I would lead a group of volunteers across the border with medical and food supplies that would be dispatched to the front line.

A year later, in March 2023, I went back to volunteer with the same charity, which, by this time, was distributing up to 3,000 freshly made pizzas a day from mobile trucks to displaced people in the recently liberated towns and villages in the east, such as Mykolaiv, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia. Often, our trucks would be serving pepperoni pizzas to hungry people within 12 miles of the fighting, well within artillery range.

We sought permission from the local police forces, but they were always on edge during our seven-hour shift. It would take only one ‘bad actor’ to send a pin-drop location to a contact on the Russian side and about 500 people lining up for their free meal would be massacred by a rocket strike. However, to see the smiling faces of Ukrainian parents (mostly women) and their children as they received their sizzling pizza was worth the personal risk to everyone on our team.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Our cycling journey across Ukraine was the idea of my fellow adventurer Paula and was intended to boost the charity’s coffers and raise awareness. Mark, an engineer, had joined me on my second stint in Ukraine and we had recently set up a business making ‘adventure’ vehicles converted from Mercedes-Benz Sprinter vans, so I called to ask if he would like to return as our support-team driver with the prototype vehicle. He agreed to loan the van without charge and at significant risk — there is no possibility of insurance in a country at war. We came up with the slogan ‘Made in Britain; Tested in Ukraine’ for a future marketing campaign for Wildbox Adventure Vehicles Ltd.

I couldn’t resist the temptation to load my penny-farthing into the back of the van alongside Paula’s speed machine. Ordinarily, I would have volunteered to ride the full distance for a challenge like this, but there were three reasons why I chose to ride just the first and last legs of each day, about 20 miles out of the daily 65. Primarily, it was Paula’s challenge and I didn’t want to steal her limelight. In addition, the performance of my penny-farthing — with its average speed of 15mph, one gear, no suspension and solid rubber tyres — is half that of a modern racing bike so I would be keeping her waiting and, finally, after recent surgery for prostate cancer, my surgeon had forbidden me to do anything strenuous.

We arrived in Odessa and met a local photographer on a mountain bike who escorted us to the beach. We talked to some local cold-water swimmers in their ‘budgie smugglers’; I, in stark contrast, was dressed in my black outfit, top hat and sat high on the penny-farthing. Ukrainian Naval patrol boats cruised the coastline of the Black Sea as we began the 400-mile journey north, using a combination of fast dual carriageways and potholed minor B roads.

Our routine was to rise at dawn with a cup of English Breakfast tea, ride mile legs during the day, then find a nice countryside camping spot hidden from public view at dusk. At the first major town, Uman, we met up with Siobhan’s Trust and spent the evening making pizzas. At Ozerna, we stopped at a café where a squad of police officers tucked into cream cakes, their automatic rifles resting on the tables. At Borodyanka — the town with the most obvious war damage — we came across the wall with the ‘David and Goliath’ painting by Banksy. We made a detour into Kyiv via Bucha, where the Russian Army committed horrific war crimes against innocent civilians, to conduct a press conference, meet local politicians and have a mini launch party for my new book, Adventureholic.

Our final leg was to Chernobyl, the location of the fateful nuclear-power-plant explosion on April 26, 1986. On our way home, in the outskirts of Lviv, we linked up with another Siobhan’s Trust team and served pizza at an orphanage. A number of children had witnessed their parents being killed. Some got the chance to ride a penny-farthing, which put a welcome smile on their little faces.

Although we had cycled across a country at war with its neighbour and had ridden through numerous military checkpoints, at no point during our journey did we feel remotely threatened, unwelcome or unsafe. It had been a memorable, challenging and eye-opening trip to a country in crisis, but whose people are incredibly defiant, proud and resilient.

To make a donation that will buy pizzas for the children of Ukraine, please visit www.justgiving.com/page/paula-reid-siobhanstrust

Why the Penny Farthing is once more a frequent sight on the streets of London

The dinosaur of the bicycle world is back in the spotlight with the help of the Penny Farthing Club and

Credit: Richards of England

The utterly inessential shopping list: The illustrious party sporran, a penny farthing for your thoughts and two liquors for the price of fun

Forget about the big things. You can keep the necessities. Don't tell us about the must-haves. Alexandra Fraser takes a

How cycling freed British people to enjoy the countryside once again

The arrival of the bicycle and tricycle opened up a thrilling freedom for the people of Britain.

Credit: Alamy

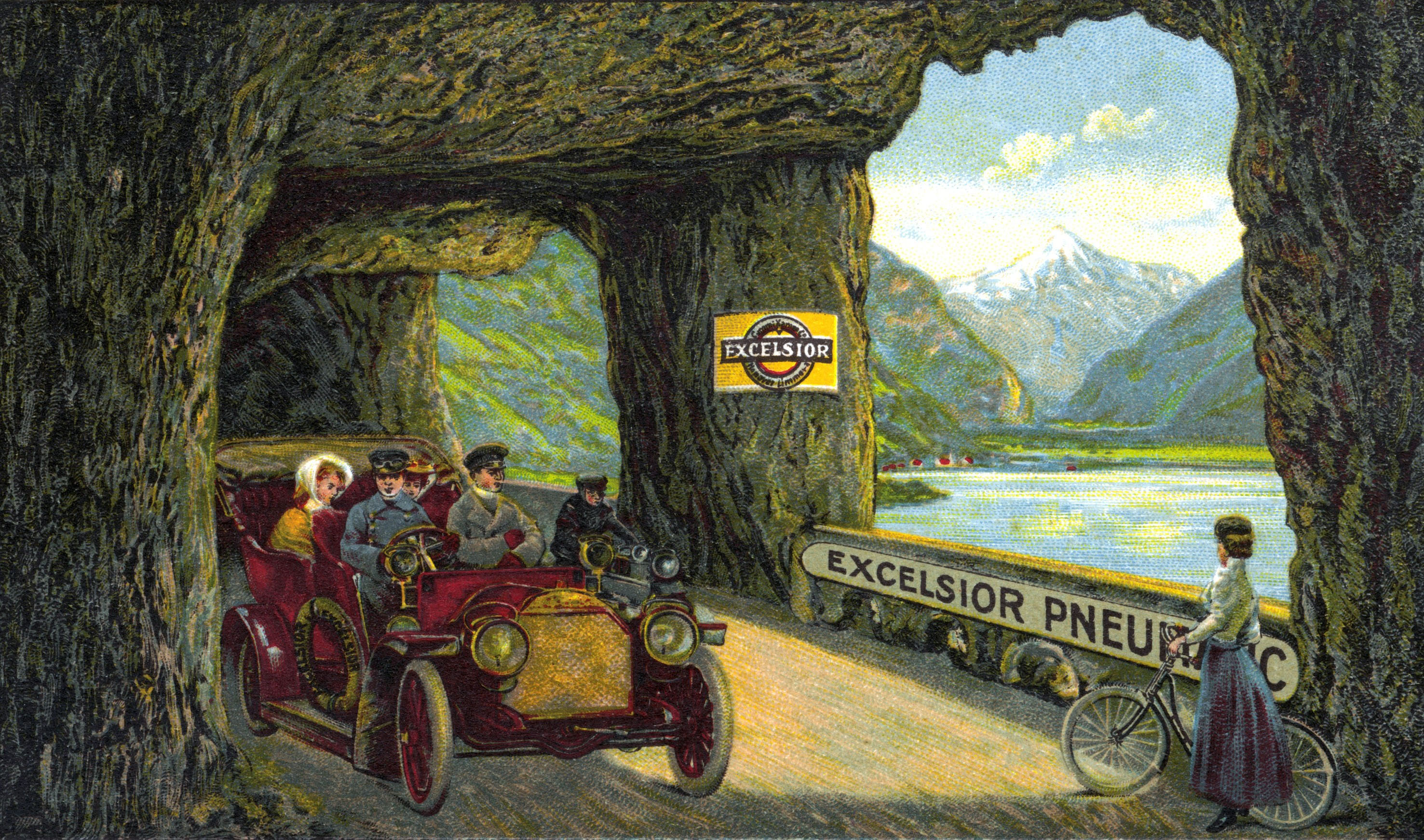

Curious Questions: Who invented the pneumatic tyre?

The names of Goodyear, Dunlop, and Michelin are familiar to motorists and cycling enthusiasts alike, but it is thanks to

-

'Comfortable, cosseting and far from the madding crowd': The recently refurbished Cornish cottage that proves Victorian decor is making a comeback

'Comfortable, cosseting and far from the madding crowd': The recently refurbished Cornish cottage that proves Victorian decor is making a comebackPlum Cottage in Padstow, Cornwall, has been brought to life by Jess Alken and her husband, Ash — and is the latest addition to their holiday cottages on the north Cornish coast.

-

How to make The Connaught Bar's legendary martini — and a few others

How to make The Connaught Bar's legendary martini — and a few othersIt's the weekend which means it's time to kick back and make yourself an ice cold martini — courtesy of The Connaught Bar.

-

From fighting for stockings to flying on the Moon: How nylon changed the world

From fighting for stockings to flying on the Moon: How nylon changed the worldAlmost 90 years after it was first discovered, Martin Fone looks at the history of this mass produced man-made fibre.

-

Curious Questions: Why do woolly hats have bobbles?

Curious Questions: Why do woolly hats have bobbles?Some can rock a bobble hat, others will always resemble Where’s Wally, but the big question is why the bobbles are there in the first place. Harry Pearson finds out as he celebrates a knitted that creation belongs on every hat rack.

-

Curious Questions: We used to fly cars across the English Channel in 20 minutes — why did we stop?

Curious Questions: We used to fly cars across the English Channel in 20 minutes — why did we stop?It seems hard to believe, but taking your car across the English Channel to France by air actually pre-dates the cross-channel car ferry. So how did it fall out of use almost 50 years ago? Martin Fone investigates.

-

Curious Questions: Who invented the rear-view mirror?

Curious Questions: Who invented the rear-view mirror?Although obvious now, the rearview mirror wasn't really invented until the 1920s. Even then, it was mostly used for driving fast and avoiding the police.

-

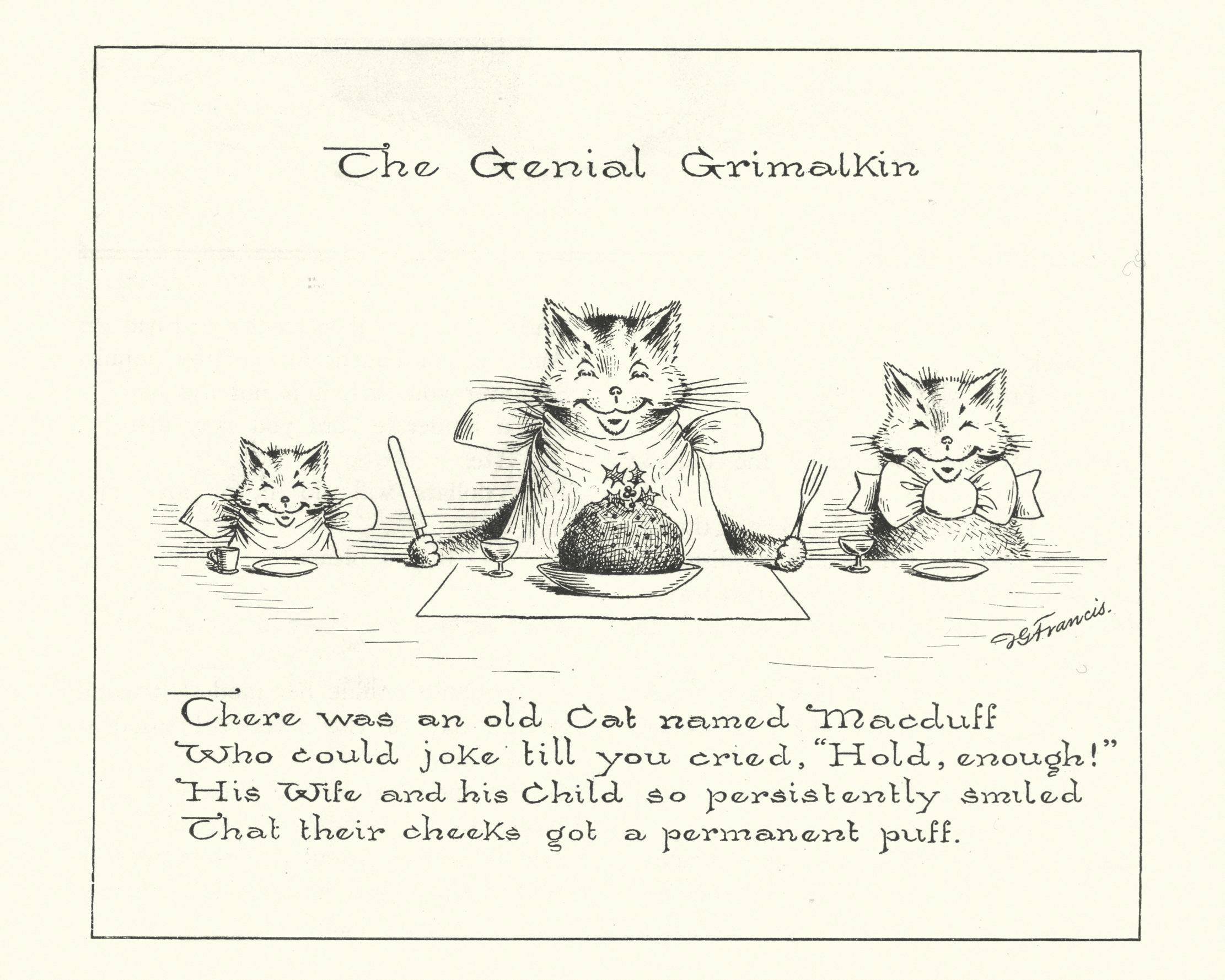

Curious Question: Did the limerick originate in Limerick?

Curious Question: Did the limerick originate in Limerick?Before workers wasted time scrolling Twitter or Instagram, they wasted their time writing limericks.

-

You rang, your majesty? What it was like to be a servant in the Royal Household

You rang, your majesty? What it was like to be a servant in the Royal HouseholdTending the royal bottom might be considered one of the worst jobs in history, but a life in elite domestic service offered many opportunities for self-advancement, finds Susan Jenkins.

-

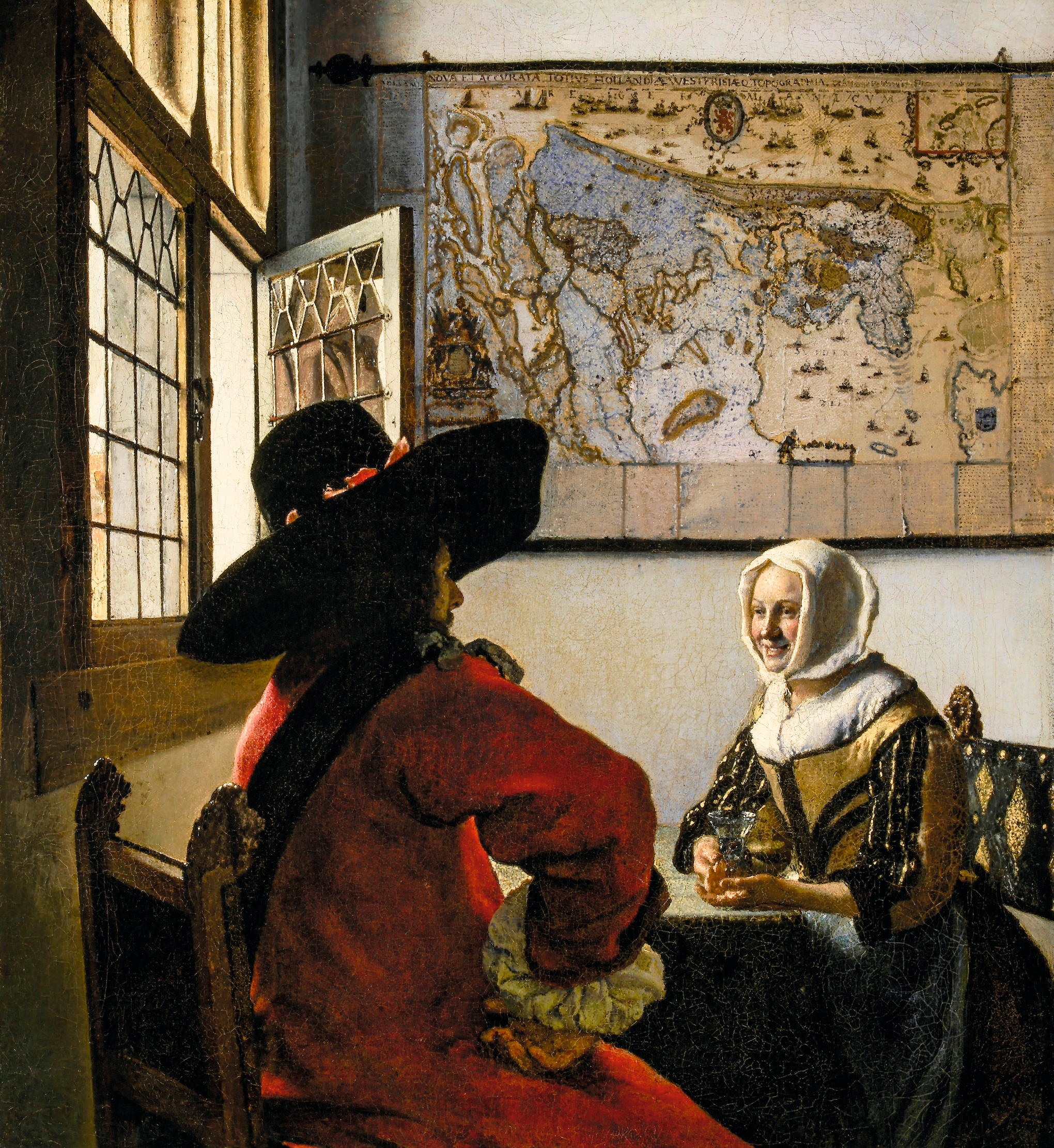

Curious Questions: Why are there so few smiles in art?

Curious Questions: Why are there so few smiles in art?Centuries of portraits down the ages — and vanishingly few in which the subjects smile. Carla Passino delves into the reasons why, and discovers some fascinating answers.

-

Tanks, tulips and taxidermy: The strange lives of Britain's most eccentric collectors

Tanks, tulips and taxidermy: The strange lives of Britain's most eccentric collectorsFive collectors of unusual things, from taxidermy to tanks, tulips to teddies, explain their passions to Country Life. Interviews by Agnes Stamp, Tiffany Daneff, Kate Green and Octavia Pollock. Photographs by Millie Pilkington, Mark Williamson and Richard Cannon.