Curious Questions: How did Abraham Lincoln come to be the only US president to hold a patent?

Statesman, lawyer, fearless leader – and part-time inventor. Martin Fone looks at one of Abraham Lincoln's lesser-known talents.

For me the pleasures to be derived from boating are outweighed by the hard work involved. As a non-swimmer, I am particularly concerned that through my clumsiness or incompetence I will end up in the water. You could call it one of my hang-ups.

Getting hung up is a serious concern for boating aficionados and describes a scenario where the vessel has become caught up or sits on a sill or ledge, natural or otherwise. In the ten years up to 2014, twenty-five canal boats in the UK alone had sunk in locks because they had ended up sitting on the lock cills. Unable to move, they become unstable, particularly if the water level changes, and, without care, can capsize. It is a not uncommon problem – the Inland Waterways Association even has a how-to guide about how to avoid it.

150 years ago, of course, there was no internet to help stranded boatmen, and even if there had been then no doubt they'd have struggled getting a 4G signal. Thus the problem attracted some great minds – no the least of which was a young man by the name of Abraham Lincoln.

Before gaining the keys to the White House and taking the USA into, and out of, a civil war to end slavery in the nation, and long before deciding to take a night off at Ford’s Theatre in Washington D.C. on 14th April 1865, Lincoln had a long and varied career.

In his youth he worked on a flatboat which worked its way down from Illinois to New Orleans. Somewhere near New Salem, on the Sangamon River, the boat got hung up on a milldam, started to take on water and began to sink. The only thing for it was to move the cargo around the boat and drain it before it capsized.

Years later, now a Congressman and returning to Illinois, the boat he was travelling became hung up on some shallows. The captain, with remarkable presence of mind, ordered his crew to put overboard all the moveable items in the ship – barrels, boxes and planks of wood – and manoeuvre them underneath. This had the effect of lifting the boat off the shelf and working it free.

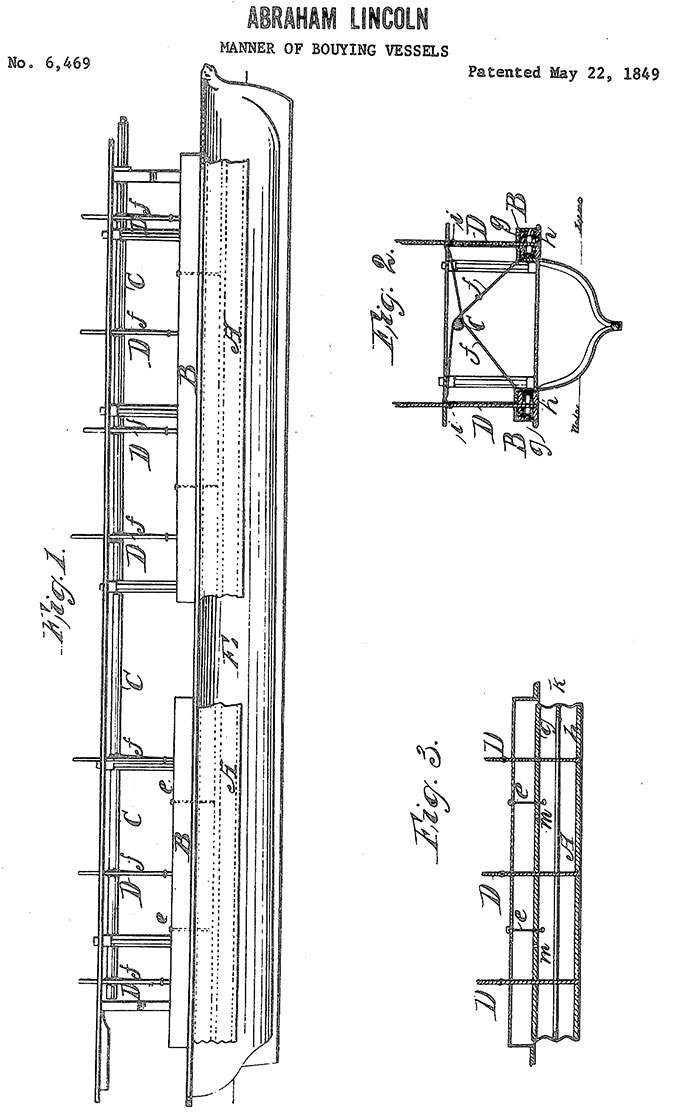

These experiences gave Lincoln pause for thought and he set about exercising his little grey cells – he didn’t wear a tall hat for nothing – to find a solution to this commonplace boating hazard. The idea he came up with was a series of bellows of 'india-rubber cloth, or other suitable water-proof fabric' attached to the underside of the vessel.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In the event that the boat got into difficulties, this ingenious device would solve the problem, as Lincoln explained: 'By turning the main shaft or shafts in one direction, the buoyant chambers will be forced downwards into the water and at the same time expanded and filled with air,' thus raising the boat off the shelf that it was sitting on.

Lincoln even went so far as to create a working model of his invention. His law partner at the time, William H Herndon, noted that Lincoln would bring a wooden model of a boat into the office and 'while whittling on it would descant on its merits and the revolution it was destined to work in steamboat navigation.'

There is a two-foot long, wooden model of Lincoln’s design at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, although whether it was made by him is open to question. His name is misspelled as Abram Lincoln – would he have been so careless? Some attribute the model to a Springfield mechanic, Walter Davis, who was known to have helped Lincoln, others to an unknown model maker in Washington who made it his business to help would-be inventors.

By this time, 1849, Lincoln was back in Springfield after just one term as a Congressman practising law. Convinced of the efficacy and practicality of his design, he applied, with the help of a lawyer, Z C Robbins, for a patent for a device for “buoying vessels over shoals.”

Patent 6469 was granted on 22nd May 1849, making Lincoln the first and only US President to have held a patent. So far, at least, no one has trumped him.

But the invention never saw the light of day and Lincoln’s revolution in steamboat navigation was still-born. Some experts, in any event, think that whilst plausible in theory, the invention was unlikely to have been very practical, because of the amount of force that would have been required to inflate the bellows to a size that they would lift the boat off the obstruction.

The design might have been capable of modification but by that time Lincoln’s mind and time was occupied on greater matters.

Martin Fone is the author of '50 Curious Questions'. His new book, '50 Scams and Hoaxes', is out now.

Curious Questions: Why do the British drive on the left?

The rest of Europe drives on the right, so why do the British drive on the left? Martin Fone, author

Curious Questions: What is the perfect hangover cure?

If there's a definite answer, it's time we knew. Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions', investigates.

Credit: Rex

Curious Questions: Why do we still use the QWERTY keyboard?

The strange layout of keyboards in the Anglophone world is as bafflingly illogical. Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions',

Credit: apples and oranges Photo by Best Shot Factory/REX/Shutterstock

Curious Questions: Can you actually compare apples and oranges?

It's repeated so often these days that we've come to regard it as a truism, but are apples and oranges

Curious Questions: Why do actors say ‘break a leg’?

The best-known phrase for wishing an actor luck is also the most baffling. Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions',

Curious Questions: How did Galileo take the credit for inventing the telescope despite being beaten to it by two Dutchmen and an Englisman?

Every schoolboy knows that Galileo Galilei invented the telescope. There's only one issue with that: he didn't. Yet what what

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.