My Favourite Painting: James Mayor

'You feel a strange affection for him as you stare at each other. I never could understand how this painting was allowed to leave the UK.'

James Mayor chooses Portrait of an Elderly Man

‘The Mauritshuis is a hidden gem. Not only does it have two world-famous Vermeers – The Girl with a Pearl Earring and View of Delft – but the gallery has two rooms of Rembrandts. In one of them, you have a real treat.

'Sitting on a bench, you have this painting to your left; in front of you, a self-portrait; and, to your right, a portrait of Homer. The reason for my choosing this one is that it isn’t exactly what you think of in a Rembrandt.

'Here is a painting of a rather pathetic old man, painted in an extremely modern way that’s unique to Rembrandt. You feel a strange affection for him as you stare at each other. I never could understand how this painting was allowed to leave the UK ’

James Mayor is a Modern art dealer, who has been running the Mayor Gallery since 1973.

John McEwen on Portrait of an Elderly Man:

Vasari wrote of Titian that his ‘last works are executed with bold strokes and dashed off with a broad and even coarse sweep of the brush’, a method that ‘makes pictures appear alive and painted with great art, but conceals the labour’.

In the 18th century, there was Goethe’s maxim: ‘Ageing is a gradual withdrawal from appearances.’ It came to define the 19th-century German notion of the Altersstil (‘old age style’), a tendency to abstraction and formal simplicity combined with emotional depth and understanding, the reward of genius. Rembrandt is its ultimate exemplar.

Such understanding could be induced by empathetic infirmity or hard-earned experience. In Rembrandt’s time, old age was reckoned to begin at 50, 60 at most. His own ‘old age’ was certainly not for cissies. In 1656, he was bankrupted; in 1663, his much younger lover died and, the year after he painted this picture, so did his only son, Titus.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

However, he wasn’t restricted by infirm-ity, as the delicacy of his touch and sheer productivity show. In the early 1660s, he painted as much as in his first glory years of the 1630s. And, although it was claimed that, in bankrupt old age, he kept company with ‘ordinary folk and practitioners of art’, he continued to have rich sitters.

Today, his last portraits are still considered an artistic apogee, exhibiting ‘the almost uncanny knowledge Rembrandt appears to have had of what the Greeks called the “workings of the soul”’ (Ernst Gombrich, The Story of Art), as we see here, in this portrait of a dishevelled, now unknown, old man. It was sold to the Mauritshuis by the trustees of the Cowdray estate, West Sussex, in 1999.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the fun

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the funFrom November, the Ford Focus will be no more. We say goodbye to the ultimate boy racer.

By Matthew MacConnell

-

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric village

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric villageA romantic experiment surrounded by the natural majesty of North Wales, Portmeirion began life as an oddity, but has evolved into an architectural phenomenon kept alive by dedication.

By Ben Lerwill

-

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite painting

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite paintingAlexia Robinson, founder of Love British Food, chooses an Edwin Landseer classic.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

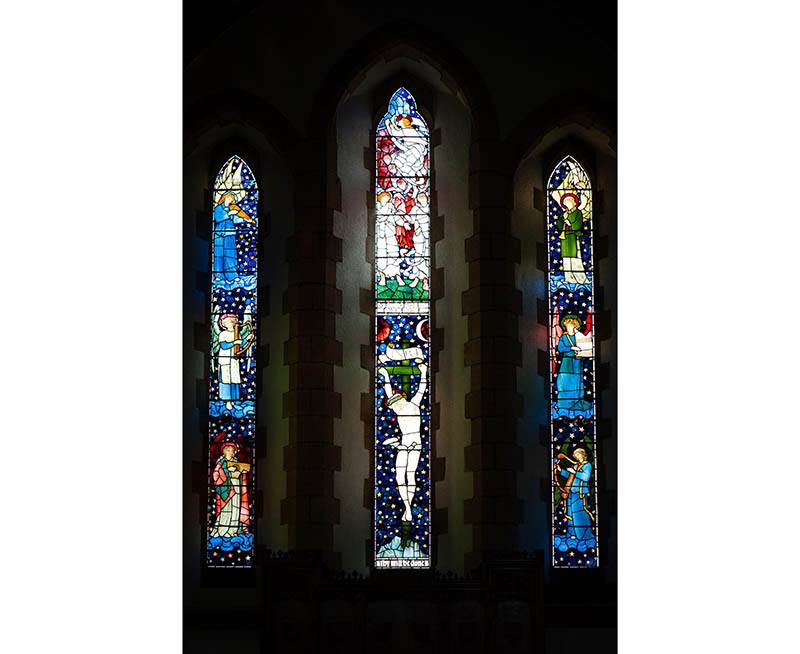

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in Britain

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in BritainThe painter Edward Burne-Jones turned from paint to glass for much of his career. James Hughes, director of the Victorian Society, chooses a glass masterpiece by Burne-Jones as his favourite 'painting'.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subject

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subjectFor Country Life's My Favourite Painting slot, the writer Emily Howes chooses a work by a daring and challenging artist: Frank Auerbach.

By Toby Keel

-

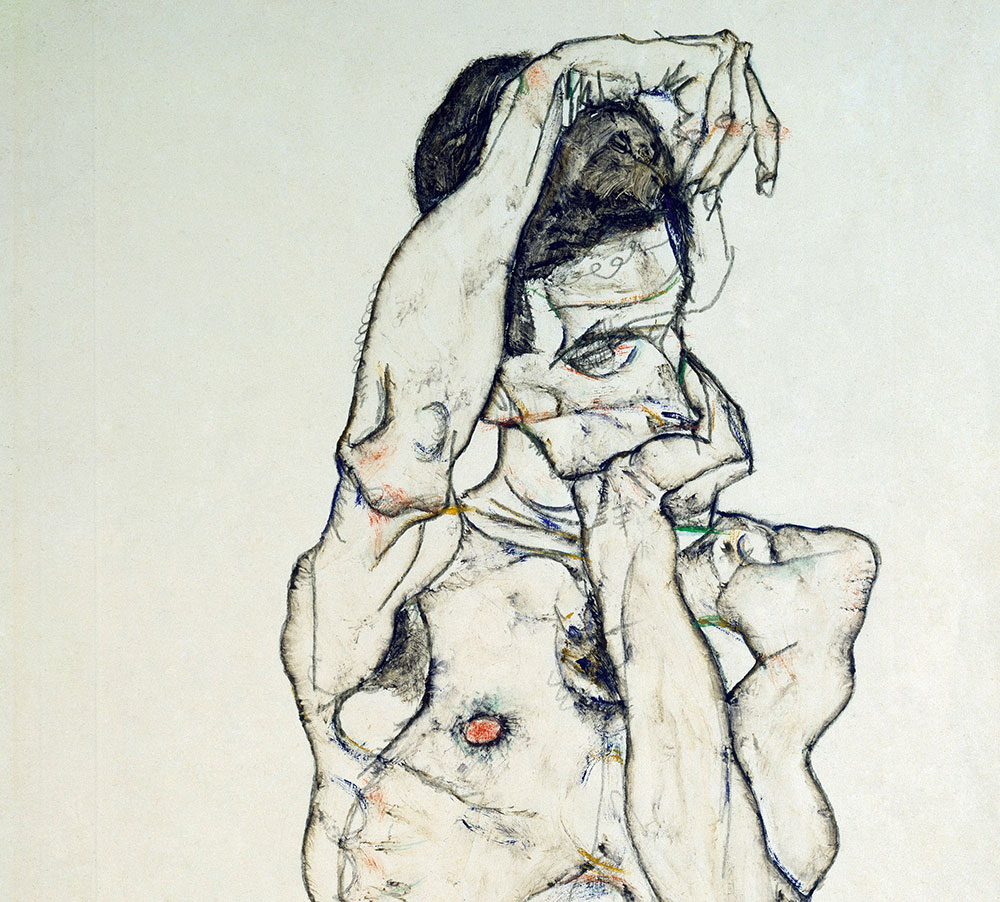

My Favourite Painting: Rob Houchen

My Favourite Painting: Rob HouchenThe actor Rob Houchen chooses a bold and challenging Egon Schiele work.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson'That's why this is my favourite painting. Because it invites you to imagine'

By Charlotte Mullins

-

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shock

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shockAs the National Gallery turns 200, the chair of its board of trustees, John Booth, chooses his favourite painting.

By Toby Keel

-

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearing

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearingChristopher Price of the Rare Breed Survival Trust on the bucolic beauty of The Magic Apple Tree by Samuel Palmer, which he nominates as his favourite painting.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon'Lesson Number One: it’s the pictures that baffle and tantalise you that stay in the mind forever .'

By Country Life