Farewell to the arms: The humbling English defeat to the French that you've never heard of

A 15th-century cannon, an 18th-century flintlock belt-pistol and two swords excavated near Castillon, the site of the battle that ended Britain's rule in south-western France, featured prominently in an Olympia Auctions sale last month.

Forgive me if I’m wrong, but might Castillon be the most significant battle of English history of which you have never heard? That could be for the usual reason: it was a defeat — and not merely a defeat, but a Hundred Years’ War ending defeat. The 300 years of Plantagenet rule had been a golden age for Bordeaux and the duchy of Guyenne, so many people were not overjoyed to be liberated by the French in 1451.

Indeed, the following year, they demanded that the English return and the redoubtable, but elderly, general John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, landed to retake the city and much of western Gascony. The French prepared their counterattack well, crucially giving command to the brothers Jean and Gaspard Bureau, who were masters of ordnance. They deployed some 300 up-to-the-minute cannons to besiege Castillon, on the Dordogne, east of Bordeaux.

Despite his age, Talbot was rash and overconfident. Rather than await reinforcements, he attempted to raise the siege and, in the ensuing battle, he and a son were killed, with perhaps half his men dead or wounded, against about 100 French. After only a century, the battlefield domination of the longbow had given way to artillery. The consequences were wide ranging and long lasting. Castillon surrendered and Bordeaux followed three months later. English rule in France was reduced to Calais and this exacerbated Henry VI’s mental breakdown, leading to the 30 years of civil conflict known as the Wars of the Roses. The French Crown was at last able to establish actual control over its territory.

In the 1970s, a quantity of swords was excavated near the battlefield, reputedly from the wreck of a barge discovered in the River Dordogne, or a tributary midway between the field and the town, now known as Castillon-la-Bataille. Still on board were two casks containing 80 swords that the late historian Ewart Oakeshott concluded had been collected from the dead. Some are said to have been sold in a Parisian flea market, others appeared more grandly at Christie’s in Geneva. The Royal Armouries made and sold replicas, as have others.

The two ‘in excavated condition’ that featured in Thomas Del Mar’s Olympia Auctions sale at the end of last month had previously been sold in 1978 and 1979 at Christie’s in London, going to Howard M. Curtis, whose collection was re-sold in 1984, again at Christie’s. I do not have the previous prices, but, here, the £60,000 (Fig 1) and £35,000 were both rather more than any might have made in the marché aux puces.

Not having the historical resonance given the swords by their find-spot, a 15th-century cannon (Fig 2), which was probably smaller than most of those that accomplished the slaughter at Castillon, sold for much less, £11,875. It may have dated from a decade or so after that battle and was German. Unfortunately, the lessons of Castillon could not be fully illustrated by this sale: although it included an archery collection, they were mostly Asian examples and there were no English longbows.

Several other items among the varied arms on offer particularly struck me. Weapons by the royal and imperial gunsmith Nicolas Noël Boutet (1761–1833) appear from time to time on the market, but here was an exceptional gold-mounted flintlock duck gun (Fig 5), probably made for presentation to the Dey of Algiers, and it made an equally exceptional £475,000.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

An 18th-century Scottish flintlock belt-pistol entirely made of steel was inscribed ‘Taken at the Battle of Colloden’ (Fig 4), but this is thought to be a hopeful — misspelt — 19th-century addition (£14,375). A round 18th-century South Indian translucent hide shield (Fig 3) decorated with a spiralling trellis design made £43,750 and the ultimate accessory for a nervous picnicker, a combined percussion pistol, knife and fork (Fig 6), made in about 1880, reached £2,750.

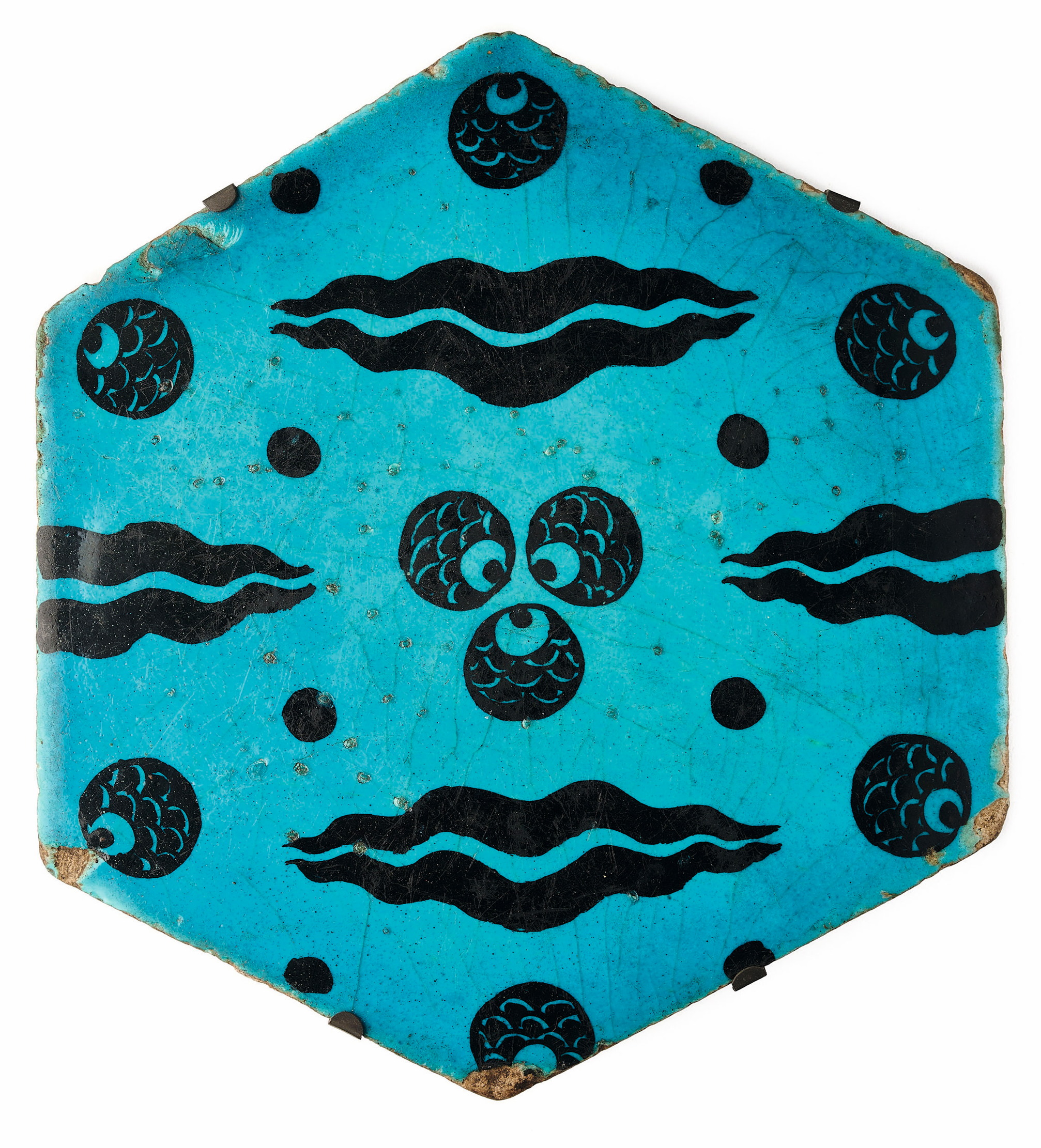

Earlier last month, an Olympia sale of Indian, Islamic and South-East Asian art, together with classical antiquities, was headed by a turquoise-glazed hexagonal tile decorated with the çintamani design (Fig 7), which reached £143,750, against an up-to-£15,000 estimate. The çintamani pattern, a cluster of three roundels representing leopard spots flanked by wavy tiger stripes, is a Buddhist and Hindu pattern derived from the Sanskrit term for auspicious jewel. It became an Ottoman motif signifying strength and power.

This large tile — the longer diametric almost 11½in — was made in Syria in the second half of the 16th century. The tiles come in two palettes, turquoise and black, or two tones of blue and apple-green on a white ground. It is not known for which building it was intended, but probably it belonged to a çintamani border surrounding a larger wall composition, as at the Rüstem Pasha Mosque (1561) in Eminönü or the Apartment of the Sacred Mantle and the Library of Ahmed III at the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul.

There is a panel of 11 such hexagonal tiles in the V&A Museum and, two years ago, a single similar tile from the collection of the theatre-costume designer Anthony Powell sold for £114,400 at Roseberys. The Olympia example had belonged to the artist Sir Howard Hodgkin (1932–2017), a keen collector of Damascus and Iznik pottery. Other items of his in the sale mostly made prices in the hundreds or low thousands, with one blue-and-white hexagonal tile fragment reaching £21,250.

Curious Questions: Why are there so few smiles in art?

Centuries of portraits down the ages — and vanishingly few in which the subjects smile. Carla Passino delves into the reasons

Credit: Photo by David Parry, courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

'The world's most joyful museum': Young V&A in East London wins top prize

The museum scooped the prestigious Museum of the Year award, the largest in the world, pocketing £120,000 after a three-year

Full steam ahead: The art of rail

The railway may have started its artistic life as a fire-breathing monster that devoured the countryside, but it soon became

The Titian masterpiece found in a plastic bag at a London bus stop has sold for £17.6 million

The painting that secured Titian’s reputation as 'the greatest painter of the Venetian Renaissance' is going up for sale, 30

After four years at Christie’s cataloguing watercolours, historian Huon Mallalieu became a freelance writer specialising in art and antiques, and for a time the property market. He has been a ‘regular casual’ with The Times since 1976, art market writer for Country Life since 1990, and writes on exhibitions in The Oldie. His Biographical Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists (1976) went through several editions. Other books include Understanding Watercolours (1985), the best-selling Antiques Roadshow A-Z of Antiques Hunting (1996), and 1066 and Rather More (2009), recounting his 12-day walk from York to Battle in the steps of King Harold’s army. His In the Ear of the Beholder will be published by Thomas Del Mar in 2025. Other interests include Shakespeare and cartoons.

-

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comeback

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comebackThe Kentish glory moth has been absent from England and Wales for around 50 years.

By Jack Watkins

-

Could Gruber's Antiques from Paddington 2 be your new Notting Hill home?

Could Gruber's Antiques from Paddington 2 be your new Notting Hill home?It was the home of Mr Gruber and his antiques in the film, but in the real world, Alice's Antiques could be yours.

By James Fisher