Diamonds are everyone's best friend: The enduring appeal of one of Nature's sparkliest treasures

Every diamond has a story to tell and each of us deserves to fall in love with one.

In ancient India, it was thought that diamonds were created when bolts of lightning struck rocks. There was a saying: ‘He who wears a diamond will see danger turn away.’ For the Egyptians, diamonds represented the sun — the symbol of power, courage and truth. The Greek philosopher Plato claimed that diamonds were living beings that embodied celestial spirits. According to the Romans, Cupid, the god of love, shot tiny, diamond-tipped arrows at people to make them fall for each other.

The supposedly cursed Hope diamond.

I love all gemstones, but I love diamonds more. I love them because they are the oldest of the gems and have travelled the furthest. I love them because they are the hardest mineral in the world: the word diamond comes from the Greek adamas, which means invincible. I love them because every single diamond, no matter how small, has a story to tell. I love them because diamond history and human history are inextricably entwined — diamonds have been sought and found, bought and sold, owned and treasured by queens and commoners, princes and pirates for thousands of years. I love them because they are rare. I love them because they are a gift given to us by Nature. I love them because certain diamonds — diamonds I have connected with in an almost spiritual way — have made me feel protected. I love them because they can be as clear as water, as brightly coloured as a parrot or as black as coal. I love them because each one is unique — a miniature work of art. Most of all, I love them because they are beautiful. Nothing can match the extra-ordinary brilliance, the fire, of a diamond.

I started buying and selling diamonds in a very modest way some 40 years ago — I had just got my first job in Fleet Street and used to wander up and down Hatton Garden in my lunch break, bothering the real dealers — but, even now, my hands still tremble with excitement when I open a brifka (the little paper envelopes used in the trade) to inspect a stone. One of the happiest days in my life was when I was elected to the London Diamond Bourse, where millions of pounds’ worth of diamonds sometimes change hands in a single day, because it allows me to indulge my obsession. Even the description of a piece of diamond jewellery — for example, ‘a tiara consisting of a graduated row of over 100ct of old European-cut, old mine-cut, old-cut pear-shaped and rose-cut diamonds, which detach to form a rivière necklace surmounted by scroll and cluster motifs’ — can set my heart racing.

Audrey Hepburn takes a break from filming Breakfast at Tiffany's — still wearing a multi-string pearl and diamond necklace. Bizarrely, none of the jewellery sported by the actress in the film was from Tiffany.

Diamonds are not only the hardest of the precious gems, they are also the oldest, having been formed between 90 million and three billion years ago. Like all gemstones, they were created in the Earth’s mantle, but in a much, much deeper part of it, where the pressure is about 50,000 times greater than on the surface and the temperature can be as high as 1,300˚C. Currents in the mantle push the diamonds upwards, but it takes volcanic eruptions through kimberlite pipes for them to reach the Earth’s crust. Of the 7,000 kimberlite pipes so far discovered on this planet, only about 60 are rich enough in natural diamonds to be worth mining. Natural diamonds are a finite resource and, since 2005, the volume being mined has fallen by more than one-third. Sooner rather than later, the supply is going to run out.

For thousands of years, the only major source of diamonds was India. The diamonds in any piece of jewellery made before the first part of the 18th century will almost certainly be Indian and probably from the world-famous Golconda mine. In 1725, however, diamonds were discovered in Brazil and, in 1867, they were found in South Africa. Slowly, the supply of diamonds increased. They were still incredibly rare and expensive, but no longer the preserve of royalty or the aristocracy. Many Victorian rings mixed diamonds with coloured gemstones and this was as much about cost as it was about taste.

You may sometimes hear a diamond described as ‘old mine cut’. This term is often misapplied. It means that the diamond has a smaller table, high crown and larger facets — the purpose being to make it sparkle under candlelight.

The first diamonds discovered by our ancestors (the oldest-known diamond ring in the world dates from about 300BC) wouldn’t have been cut or polished — partly because the technology didn’t exist and partly because, in many ancient societies, it was believed that if a stone were broken, its spirit would be released and thus lost. Another ancient belief, still held in many cultures today, was that the back of a gemstone needed to be touching the skin for the owner to benefit fully from its energy and powers.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

A girl’s best friend: Marilyn Monroe in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953).

It wasn’t until the middle of the 14th century that diamonds were fashioned with a symmetrical arrangement of polished facets, designed to show the brilliance (sparkle) and fire (rainbow colours) of the stone. Early cuts include the table cut (a square shape) and the rose cut (made up of many triangular facets). As technology improved and more cutting tools became available, more types of cut with more intricate designs and a larger number of facets became possible. For 300 years, beginning in the 16th century, London was the most important cutting centre in the world.

Over the centuries, different methods and terminology have been employed to value diamonds. In the 16th century, for example, merchants used terms such as ‘tincture’ and ‘tint’ to describe a diamond’s colour and expressions such as ‘made well’ and ‘made poorly’ to describe its cut. Diamonds were often compared to water — the more translucent or the more like water, the higher the quality — the best being described as ‘diamonds of the first water’. Shakespeare alludes to this in Pericles, which was published in 1609:

'Heavenly jewels which Pericles hath lost, Begin to part their fringes of bright gold. The diamonds of a most praisèd water Doth appear, to make the world twice rich.'

The one term that has stood the test of time is ‘carat’ (or ct), which originates from Ceratonia siliqua, commonly known as the carob tree. In ancient times, before scales and units of mass were invented, diamond traders compared the weight of a diamond to the seeds of the carob tree.

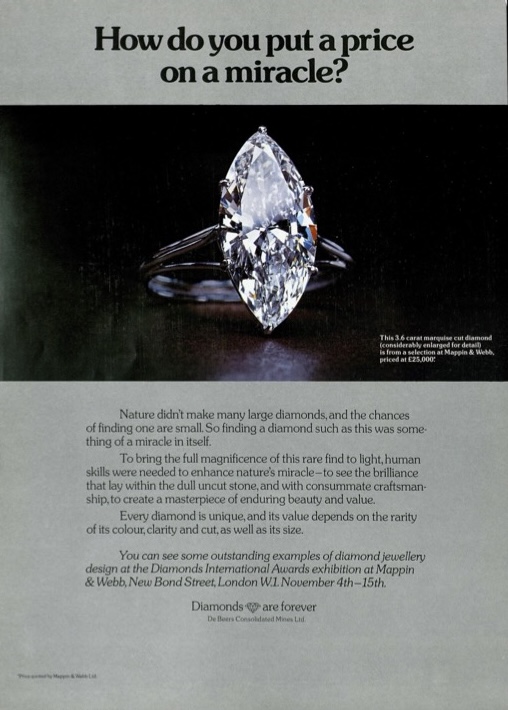

Diamond rings have been given and exchanged before and after marriage for thousands of years. For example, a poem written in 1475 to celebrate the union of Costanzo Sforza and Camilla d’Aragona, who belonged to two of the most influential families in Italy, includes the words: ‘Two wills, two hearts, two passions are bonded in marriage by a diamond.’ However, it wasn’t until after the Second World War that diamonds truly became synonymous with eternal love. Against a background of economic upheaval, when people were saving rather than spending, De Beers, the largest diamond producer in the world, commissioned a New York advertising agency to come up with a campaign to boost sales. The resulting slogan, ‘A Diamond is Forever’, conveyed the idea that a diamond, like true love, is everlasting, unbreakable and invaluable.

A truer word was never spoken.

After trying various jobs (farmer, hospital orderly, shop assistant, door-to-door salesman, art director, childminder and others beside) Jonathan Self became a writer. His work has appeared in a wide selection of publications including Country Life, Vanity Fair, You Magazine, The Guardian, The Daily Mail and The Daily Telegraph.

-

Hidden excellence in a £7.5 million north London home

Hidden excellence in a £7.5 million north London homeBehind the traditional façades of Provost Road, you will find something very special.

By James Fisher

-

RHS Chelsea Flower Show: Everything you need to know, plus our top tips and tricks

RHS Chelsea Flower Show: Everything you need to know, plus our top tips and tricksCountry Life editors and contributor share their tips and tricks for making the most of Chelsea.

By Amie Elizabeth White

-

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old Masters

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old MastersThe younger generations’ appetite for everything vintage bodes well for the future, says Huon Mallalieu, at a time when an extraordinary Old Masters collection is about to go under the hammer.

By Huon Mallalieu

-

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication'The Great Gatsby' sold poorly the year it was published, but, in the following century, it went on to become a cornerstone of world literature.

By Carla Passino

-

Shark tanks, crocodile lagoons, laser defences, and a subterranean shooting gallery — nothing is impossible when making the ultimate garage

Shark tanks, crocodile lagoons, laser defences, and a subterranean shooting gallery — nothing is impossible when making the ultimate garageTo collectors, cars are more than just transport — they are works of art. And the buildings used to store them are starting to resemble galleries.

By Adam Hay-Nicholls

-

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of spring

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of springThe biggest-ever David Hockney show has opened inside the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris — in time for the season that the artist has become synonymous with.

By Amy Serafin

-

Under the hammer: A pair of Van Cleef & Arpels earrings with an intriguing connection to Princess Grace of Monaco

Under the hammer: A pair of Van Cleef & Arpels earrings with an intriguing connection to Princess Grace of MonacoA pair of platinum, pearl and diamond earrings of the same design, maker and period as those commissioned for Grace Kelly’s wedding head to auction.

By Rosie Paterson

-

Why LOEWE decided to reimagine the teapot, 25 great designs over

Why LOEWE decided to reimagine the teapot, 25 great designs overLoewe has commissioned 25 world-leading artists to design a teapot, in time for Salone del Mobile.

By Amie Elizabeth White

-

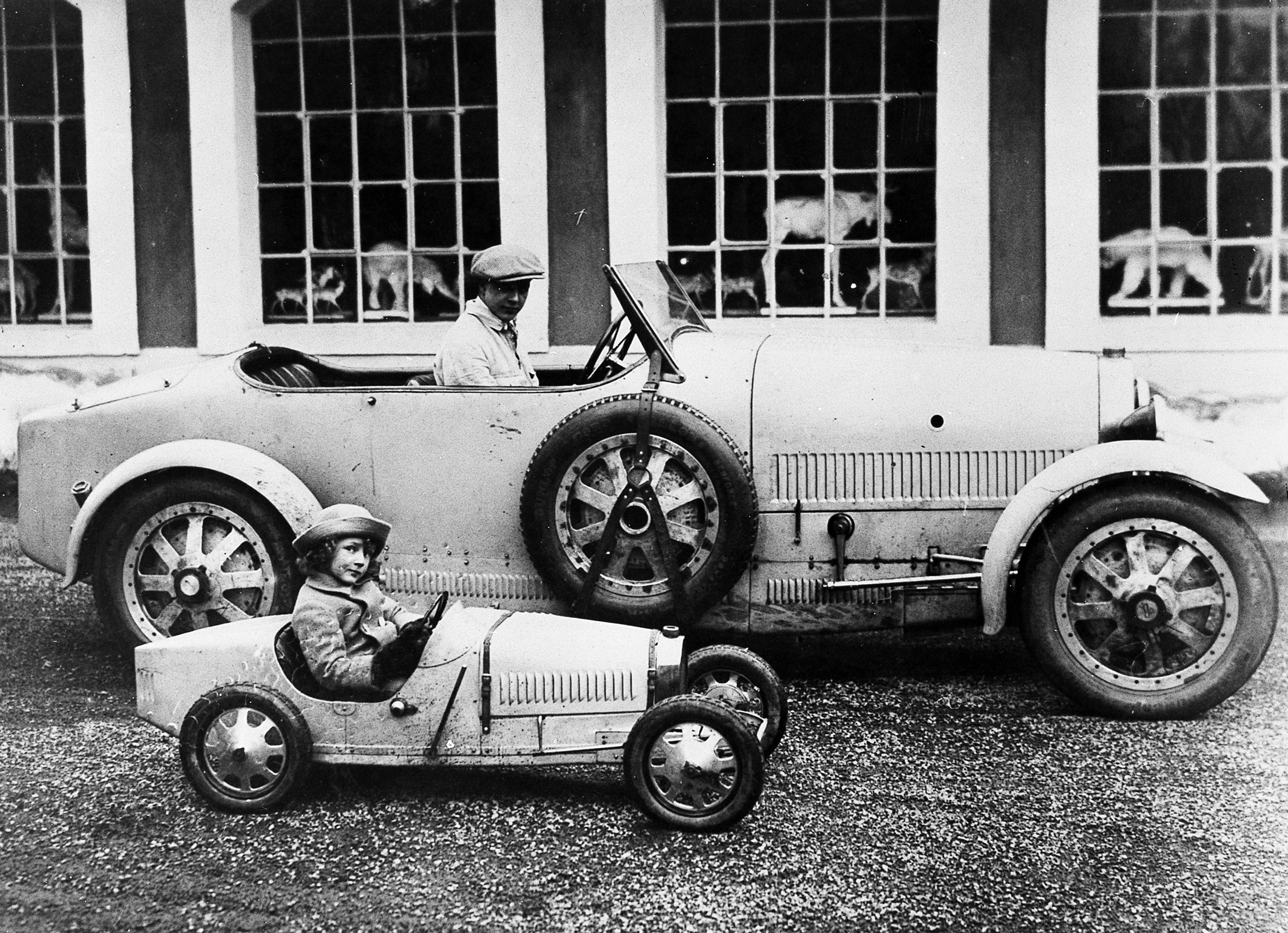

The brilliant Bugattis: Sculpture, silverware, furniture and the fastest cars in the world

The brilliant Bugattis: Sculpture, silverware, furniture and the fastest cars in the worldA new exhibition at this year's Treasure House Fair will shine a light on the many talents of the Bugatti dynasty.

By James Fisher

-

Big, bright and bold: Colourful luggage to inspire your next spring getaway

Big, bright and bold: Colourful luggage to inspire your next spring getawayIf RIMOWA's new 'Holiday' campaign is anything to go by, then conservative-coloured luggage is out and eye-catching is in.

By Rosie Paterson