Curious Questions: Why do Scots carry sgian-dubhs with their kilts when donning traditional dress?

Once essential elements of every brave Highlander’s armoury, deadly dirks and sgian-dubhs provided protection against foes, the elfin race and broken oaths. Joe Gibbs traces their history and explains how they came to be part of the traditional Scottish outfit, along with the kilt and sporran.

In 1910, there appeared in Inverness a catalogue for the auction of stock from John Munro’s Old Curiosity Shop in Castle Street. Lot 377a was ‘an old dirk with ivory handle inlaid with gold’.

A colourful tale is attached to this weapon. It had, so the story went, belonged to Alexander Fraser, son of Thomas, Lord Lovat, a local clan chieftain. In about 1700, Fraser had attended a wedding at Teawig, a farm that still sits on a sharp bend in the road near the village of Beauly in Inverness-shire. The property was an island of Clan Chisholm ownership amid vast Fraser landholdings. A young Miss Chisholm was to marry and a piper was engaged for the nuptials, one MacThòmais.

Seeing Fraser there and fond of a tease, the piper struck up a tune that insulted his family. In response, Fraser drew his dirk and, although later claiming only to have wanted to rip the bag of the pipes, pierced the heart of MacThòmais, which lay behind it, mortally wounding him.

Fraser fled to concealment in Wales, from whence one of his descendants later claimed back the Lovat lands and title. The same story was attached to Fraser’s brother John, whose descendant brought a separate, but similar, earlier action in the House of Lords.

Had Fraser heeded the old Scots saying ‘never draw your dirk when a blow will suffice’, he might have saved his family no end of trouble and expense in the centuries that ensued. Happily, at least the tale gave rise to the reel ‘Thomson wears a Dirk’.

The Jacobite rebellions that were quashed in 1746, at the Battle of Culloden, brought in their wake the British government’s Act of Proscription, which banned Highland dress and included ‘poignard, whinger or durk’ among weapons that could not be borne above the Highland line. After the successful campaign to emasculate the clans and their chiefs after Culloden and the reversal of the act in 1782, bearing arms became superfluous.

However, until then, the dirk had been an everyday part of a Highlander’s personal weaponry, more affordable than a sword and, therefore, more ubiquitous. Its origins lay in a similar weapon called the ballock knife, found in several European countries up to the 16th century. This had two oval swellings resembling testes at the base of the hilt, giving it the epithet ‘bollock dagger’. A leather sheath contained the knife and it dangled between the legs, available to either hand, adding still further to its phallic presence.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In the 17th century, the ballock morphed into the Highland dirk. Handles were made of box, ivy root or bog oak — buried in peat bogs for centuries — and were intricately decorated with finely carved Celtic knotwork. The blade, broad in the back and sharp at the point, could run as long as 25in and was thin and double-edged, perhaps made from a broken sword ground down by blacksmiths.

Often, the blade was given fullering or blood grooves to allow easier withdrawal and, sometimes, the spine was gimped with dull saw teeth. The twin ovals at the base of the handle gave way to tapered haunches and a pronounced pommel.

In battle, some Highlanders, who carried targes or shields looped onto their left arms, held their dirks pointing downwards in their left hands. David Morier’s painting, created shortly after Culloden and posed for by Jacobite prisoners, shows one such combatant, yet dirks really only came into play when fighting was at too close quarters to use a sword.

The sheath of a dirk could house a by-knife, a smaller blade used for skinning and eating. Concealed in their tunic sleeves in the left armpit, Highlanders also carried a sgian-achlais, an armpit dagger. Edmund Burt, in his letters from the North of Scotland written in 1730, thought that the sgian-achlais was ‘more peculiar to robbers who have done mischief with it, when thought to be… disarmed’.

However, as cattle reiving was a universal recreation, he was probably covering quite a wide section of the populace. On arrival at a friendly house, arms would be left at the door and the sgian-achlais set in plain view, in a stocking top. From this custom may have come the later idea of the sgian-dubh, the small black knife that you see today’s Highlander wearing in his stocking, which is a much later introduction.

With the dawning of the tartan-mania stoked up by Sir Walter Scott and others came a revival of Highland dress accoutrements. No longer needed for battle, dirks became purely ceremonial. Metalwork on sheath and handle became ornate; blades were single-edged and, sometimes, solid silver, capable of slotting a haggis on Burns night, but little else. Huge citrine quartz stones — Cairngorms — decorated the pommels, which were tilted to show off the stone to better advantage, and by-knife and fork became essentials. Scottish regiments adopted distinguishing styles of dirk.

Clan chiefs acquired boxed suites of matching Highland regalia that, as well as dirk and sgian-dubh, contained silver cross belts, powder horn and chain, plaid brooch, buttons, buckles, epaulettes and splendid sporran with detachable tassels. Iain Marr, a Beauly dealer in Highland regalia, estimates the value of a high-quality Victorian dirk made by an Edinburgh or provincial silversmith as being £3,000 and a sgian-dubh as £600. If you are lucky enough to find either made of rare Tain silver, you can multiply the value by five.

With their silver blades, dirks literally lost some of their charm. There was a great belief in the Highlands that iron or steel offered protection against the elfin race. The metals were considered holy. Oaths were sworn by kissing a dirk, which implied consent to being stabbed with that weapon if proven perjured.

A less reverent attitude was displayed in the game of Iomlaid Bhiodag, or dirk-swapping. Lights were extinguished, all dirks cast under the table and shuffled with a staff, before a blindfolded member of the company — his right arm tied to his side and his left hand gloved — retrieved the dirks and handed them in rotation to the players, each of whom was on a knife edge to see what quality of weapon he received back. Thank heavens for the advent of Scrabble.

Spectacular Scottish castles and estates for sale

A look at the finest castles, country houses and estates for sale in Scotland today.

Credit: Highland Games (Getty)

The Highland Games: Dancing, bagpipes and giant men in kilts since 1314

In her 1931 novel Highland Fling, Nancy Mitford described the Highland games at Invertochie as ‘an extraordinary spectacle of apparently

Credit: Alamy

The bagpipe-maker: 'The older customers want me to make their pipes sharpish; they want to be sure they’re not dead before they get to play them!'

Hours of intricate work are needed to craft a set of bagpipes. Kate Lovell spoke to bagpipe-maker Dave Shaw to

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagne

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagneAn upwardly mobile spaghetti Bolognese, lasagne al forno, with oozing béchamel and layered meaty magnificence, is a bona fide comfort classic, declares Tom Parker Bowles.

By Tom Parker Bowles

-

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025Thursday's Quiz of the Day asks exactly how popular Baywatch became.

By Toby Keel

-

From fighting for stockings to flying on the Moon: How nylon changed the world

From fighting for stockings to flying on the Moon: How nylon changed the worldAlmost 90 years after it was first discovered, Martin Fone looks at the history of this mass produced man-made fibre.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Why do woolly hats have bobbles?

Curious Questions: Why do woolly hats have bobbles?Some can rock a bobble hat, others will always resemble Where’s Wally, but the big question is why the bobbles are there in the first place. Harry Pearson finds out as he celebrates a knitted that creation belongs on every hat rack.

By Harry Pearson

-

Curious Questions: We used to fly cars across the English Channel in 20 minutes — why did we stop?

Curious Questions: We used to fly cars across the English Channel in 20 minutes — why did we stop?It seems hard to believe, but taking your car across the English Channel to France by air actually pre-dates the cross-channel car ferry. So how did it fall out of use almost 50 years ago? Martin Fone investigates.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Who invented the rear-view mirror?

Curious Questions: Who invented the rear-view mirror?Although obvious now, the rearview mirror wasn't really invented until the 1920s. Even then, it was mostly used for driving fast and avoiding the police.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Question: Did the limerick originate in Limerick?

Curious Question: Did the limerick originate in Limerick?Before workers wasted time scrolling Twitter or Instagram, they wasted their time writing limericks.

By Martin Fone

-

You rang, your majesty? What it was like to be a servant in the Royal Household

You rang, your majesty? What it was like to be a servant in the Royal HouseholdTending the royal bottom might be considered one of the worst jobs in history, but a life in elite domestic service offered many opportunities for self-advancement, finds Susan Jenkins.

By Country Life

-

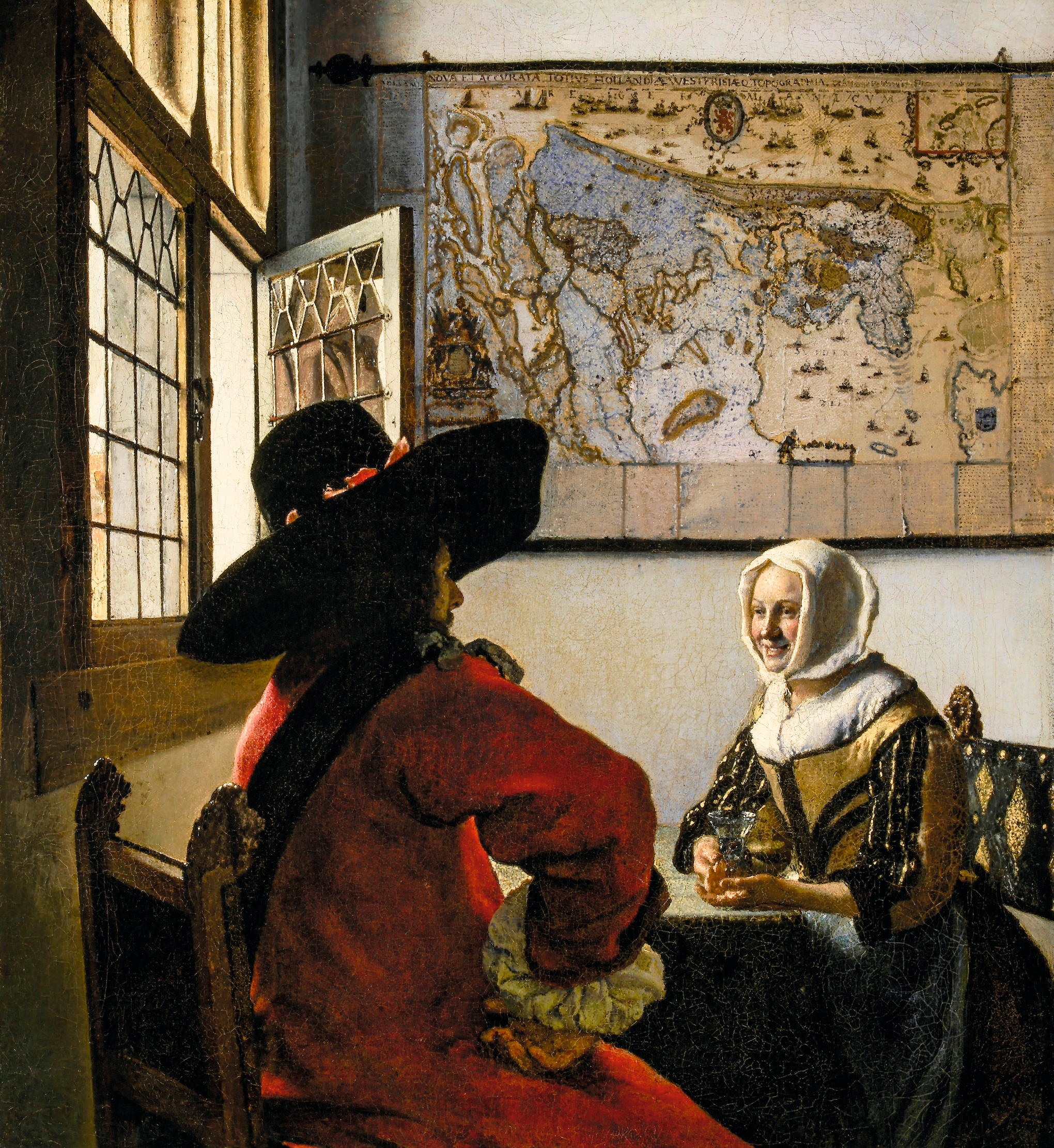

Curious Questions: Why are there so few smiles in art?

Curious Questions: Why are there so few smiles in art?Centuries of portraits down the ages — and vanishingly few in which the subjects smile. Carla Passino delves into the reasons why, and discovers some fascinating answers.

By Carla Passino

-

Tanks, tulips and taxidermy: The strange lives of Britain's most eccentric collectors

Tanks, tulips and taxidermy: The strange lives of Britain's most eccentric collectorsFive collectors of unusual things, from taxidermy to tanks, tulips to teddies, explain their passions to Country Life. Interviews by Agnes Stamp, Tiffany Daneff, Kate Green and Octavia Pollock. Photographs by Millie Pilkington, Mark Williamson and Richard Cannon.

By Agnes Stamp