Curious Questions: Why do we say 'Merry Christmas' instead of 'Happy Christmas'?

Have you ever stopped to wonder why we say 'Merry Christmas' when for every other occasion we use the word 'happy' instead'? Probably not, but now we've pointed it out the reason will bug you until you've read the answer.

Merry Christmas! Blithely do we use this phrase as greeting, farewell or exclamation of joy with little thought to the book that made it famous. Although it was in use from the 16th century, it was Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol –published exactly 175 years ago – that really popularised it.

By the same token, ‘Bah! Humbug!’ entered popular usage, and everyone knows what it means to be called a Scrooge (even if they’ve never read the book) – a miserly grouch who believes that ‘Every idiot who goes about with “Merry Christmas” on his lips, should be boiled with his own pudding, and buried with a stake of holly through his heart’. He is pictured below with the jovial Ghost of Christmas Present.

Published on December 19, 1843, with the first edition sold out by Christmas Eve, the didactic novella’s legacy further extends to an almost immediate rise in charitable giving, recorded in The Gentleman’s Magazine in 1844: for years afterwards, Maud of Wales, Queen of Norway, sent gifts to London’s crippled children signed ‘With Tiny Tim’s Love’.

At the time, Dickens was gravely concerned with the growing masses of poor, hungry and uneducated, particularly children. Six months after the book’s publication, the Factories Act decreed that children between the ages of nine and 13 could work only nine hours a day, six days a week maximum, which was considered humane. We tend to think of Dickens as balding, bearded and avuncular, but when he wrote A Christmas Carol he was young, energetic and crusading – shown by a recently-unearthed portrait of the writer that was painted in 1843.

Given Dickens’s charitable leanings, the book was bizarrely extravagant in its first edition (which he funded himself), in ‘brown-salmon fine-ribbed cloth, blocked in blind and gold on front; in gold on the spine… all edges gilt’, costing 5s.

Even so, since 1943, it has never been out of print, it’s the most adapted of all Dickens’s works and still embodies the spirit of Christmas goodwill for many. God bless us, every one!

A Christmas Carol’s denouement – with Tim fetching a turkey from the butcher – is just one example of the pivotal role of food in Dickens’s stories. Those associations are being explored at the moment in a new exhibition at the Charles Dickens Museum, London WC1, ‘Food Glorious Food: Dinner with Dickens’, which also looks at food with respect to how it represented the author’s sense of social justice,. Upon entering the house, visitors are invited to experience the exhibition as either a servant or a guest – see www.dickensmuseum.com for more details.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Credit: Alamy

Six audiobooks for Christmas, from Dickens to the latest Booker Prize winner

For book lovers who never get the time to read, audiobooks can make a great present. We've picked out five

Credit: http://thestarandgarterlondon.co.uk

The Richmond landmark overlooking Britain's only listed view to open its doors

One of Richmond's most recognisable landmarks has been converted into plush apartments. Eleanor Doughty reports on The Star and Garter.

The best places in Britain to go and hear Christmas choir services over the festive period

Katy Birchall takes a look at the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols at King’s College, Cambridge, and picks out

Annunciata grew up in the wilds of Lancashire and now lives in Hampshire with a husband, two daughters and an awful pug called Parsley. She’s been floating round the Country Life office for more than a decade, her work winning the Property Magazine of the Year Award in 2022 (Property Press Awards). Before that, she had a two-year stint writing ‘all kinds of fiction’ for The Sunday Times Travel Magazine, worked in internal comms for Country Life’s publisher (which has had many names in recent years but was then called IPC Media), and spent another year researching for a historical biographer, whose then primary focus was Graham Greene and John Henry Newman and whose filing system was a collection of wardrobes and chests of drawers filled with torn scraps of paper. During this time, she regularly gave tours of 17th-century Milton Manor, Oxfordshire, which may or may not have been designed by Inigo Jones, and co-founded a literary, art and music festival, at which Johnny Flynn headlined. When not writing and editing for Country Life, Annunciata is also a director of TIN MAN ART, a contemporary art gallery founded in 2021 by her husband, James Elwes.

-

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life

-

The coveted Hermès Birkin bag is a safer investment than gold — and several rare editions are being auctioned off by Christie’s

The coveted Hermès Birkin bag is a safer investment than gold — and several rare editions are being auctioned off by Christie’sThere are only 200,000 Birkin bags in circulation which has helped push prices of second-hand ones up.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the fun

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the funFrom November, the Ford Focus will be no more. We say goodbye to the ultimate boy racer.

By Matthew MacConnell

-

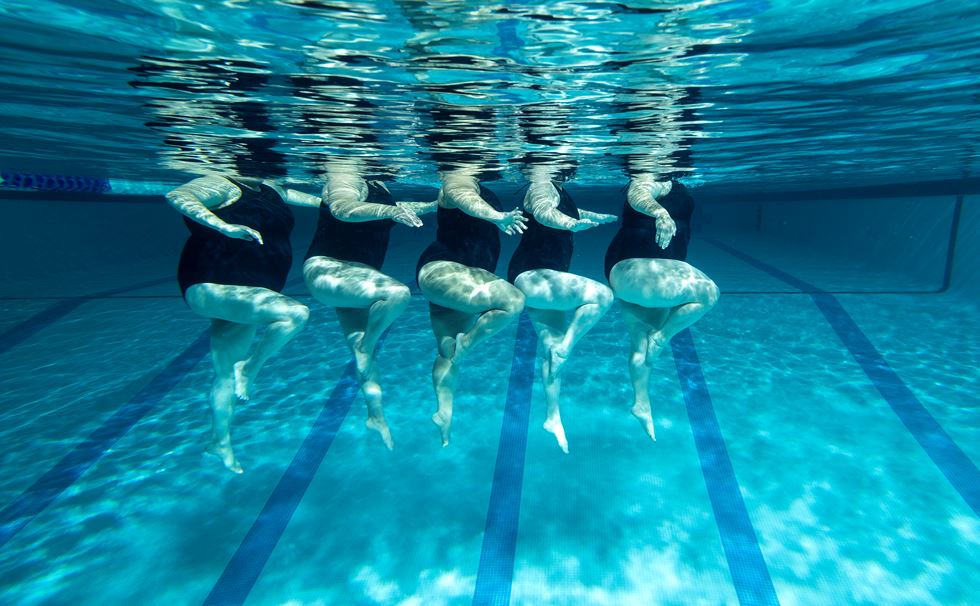

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead Heath

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead HeathEmma Hughes dives into swimming's hidden depths at the Design Museum's exhibit in London.

By Emma Hughes

-

Diamonds are everyone's best friend: The enduring appeal of one of Nature's sparkliest treasures

Diamonds are everyone's best friend: The enduring appeal of one of Nature's sparkliest treasuresEvery diamond has a story to tell and each of us deserves to fall in love with one.

By Jonathan Self

-

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old Masters

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old MastersThe younger generations’ appetite for everything vintage bodes well for the future, says Huon Mallalieu, at a time when an extraordinary Old Masters collection is about to go under the hammer.

By Huon Mallalieu

-

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication'The Great Gatsby' sold poorly the year it was published, but, in the following century, it went on to become a cornerstone of world literature.

By Carla Passino

-

Shark tanks, crocodile lagoons, laser defences, and a subterranean shooting gallery — nothing is impossible when making the ultimate garage

Shark tanks, crocodile lagoons, laser defences, and a subterranean shooting gallery — nothing is impossible when making the ultimate garageTo collectors, cars are more than just transport — they are works of art. And the buildings used to store them are starting to resemble galleries.

By Adam Hay-Nicholls

-

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of spring

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of springThe biggest-ever David Hockney show has opened inside the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris — in time for the season that the artist has become synonymous with.

By Amy Serafin