When England cancelled Christmas

No feasting. No drinking. No celebrations. Ian Morton explores what the festive period was like when Oliver Cromwell’s Christmas clampdown gripped the nation.

Why do we celebrate Christ’s birth in late December? All ancient cultures recognised the winter solstice. The Romans spent the seven days of Saturnalia in feasting and carousing, upending normality with masquerades, slaves posing as masters and masters posing as slaves. Norse communities lit bonfires and sat around eating, drinking and telling tales. In Britain, the Celtic priests cut and blessed mistletoe from sacred oaks and burned yule logs to banish darkness and evil spirits, firstly to encourage good fortune during the 12 days they believed the sun stood still and secondly to welcome its return.

When early Christians joined the party, syncretism occurred naturally. Many churches were located on already hallowed sites and, in an era of healthy paganism and widespread naturalistic tradition, when else in the year should the embryonic church establish its founder’s birth? His Mass and its attendant festivities had arrived. However, in Britain during the fourth decade of the 17th century, the ancient tradition was under challenge.

The country was in upheaval: the King had dissolved Parliament, Parliament had reasserted itself with a Puritan mandate, the first battles had been fought in the Civil War and, in the midst of this turmoil, Christmas was officially cancelled.

As far as the new fundamentalist administration was concerned, the ungodly had brought it upon themselves by festive over-indulgence. A Parliamentary ordinance of December 19, 1643, required the populace to treat Christmas with ‘solemn humiliation’ instead of ‘giving liberty to carnal and sensual delights’. The following year, an altogether stiffer ruling emphasised the fierce anti-Catholic nature of the emergent government.

"When a Canterbury shopkeeper was put in the stocks for refusing to open on Christmas Day, the townsfolk rallied in what became known as the Plum Pudding Riots"

A Directory for Public Worship was published to replace the Book of Common Prayer, which was dismissed as a ‘liturgy for the most part framed out of the Romish breviary, rituals and Mass’. It was decreed that saints’ days and Christian festivals had no Biblical justification. ‘Festival days, vulgarly called Holy days, having no warrant in the Word of God, are not to be continued,’ declared the document.

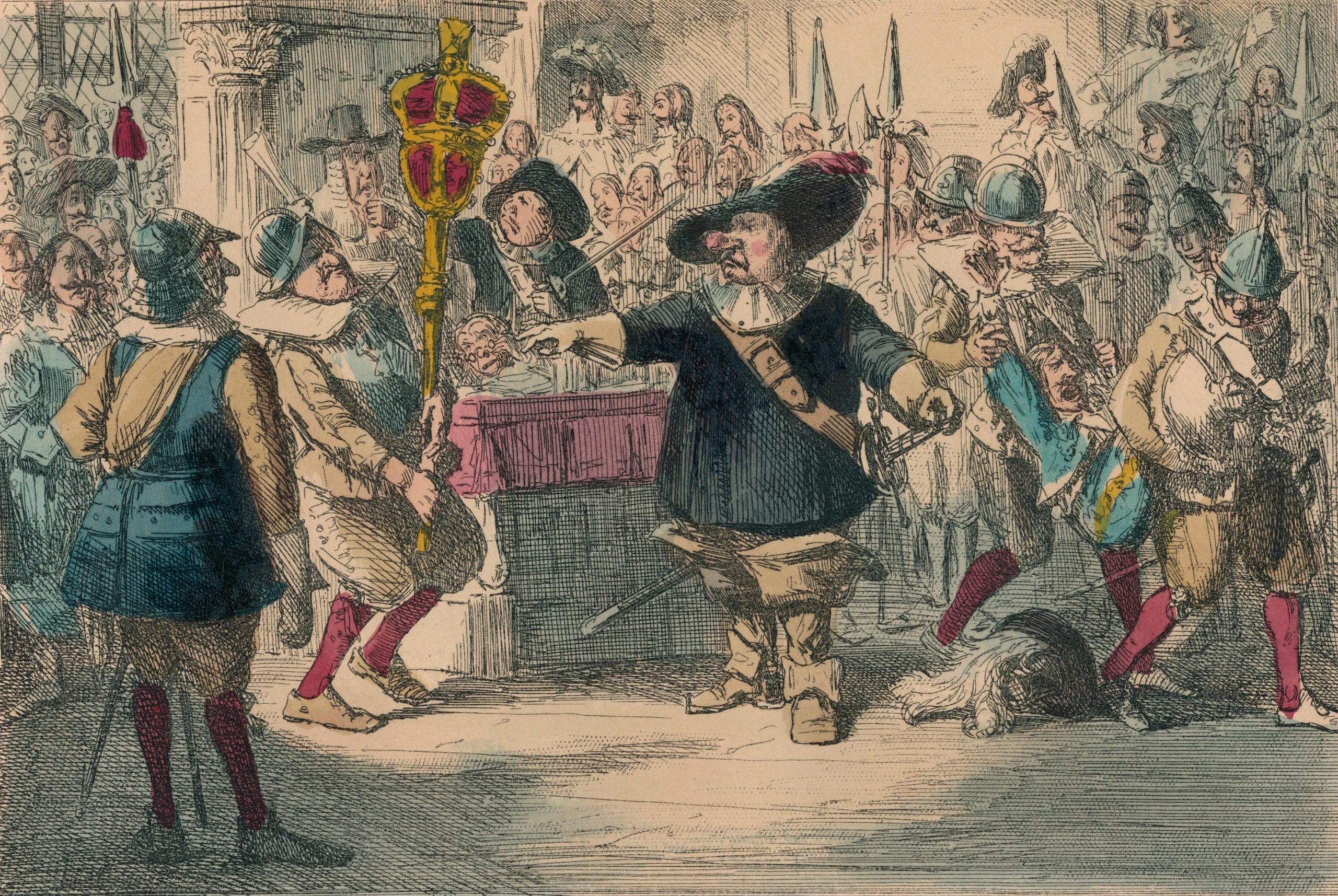

Christmas was expunged from the calendar and all celebrations banned. Shops were to remain open. Decorative displays of holly, ivy, rosemary and bay were ‘pagan’ and forbidden. Constables were given power to examine the contents of ovens and to confiscate dishes deemed festive. Plum puddings and mince pies were outlawed. Military patrols took to city streets to enforce the bans. Easter and Whitsun celebrations were later added to the proscribed list. With decisive military battles won, the Puritans were confident of their grip — the grip of the self-righteous.

Yet 1647 proved them wrong. Seasonal celebration may have retreated behind closed doors, but, when the mayor of Canterbury put a shopkeeper in the stocks for refusing to open on Christmas Day, the townsfolk rallied. In what became known as the Plum Pudding Riots, an angry crowd gathered and windows of known Puritans were smashed. The mayor was jostled and felled, his robes torn, and he was obliged to flee. Similar incidents occurred in London, Norwich, Ipswich and Bury St Edmunds, with the spirit of rebellion spreading to Kentish ports, where sailors mutinied and occupied Deal, Sandwich and Walmer and laid siege to Dover.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

A new phase in the Civil War followed. Charles I was executed, Parliamentary rule became absolute, the cause for King and Christmas lapsed into sullen public resentment and it would be 1660 before the monarchy and Christmas were restored. Meanwhile, the Pilgrim Fathers had carried their grim Puritanism to the New World and, in their settlements on the mid-17th-century east coast, they banned Christmas equally forcefully. Yet Dutch settlers to the north in New Amsterdam had their own cultural icon, variously known as Sinterklaus, Santa Claus, St Nicholas or Kris Kringle. They had no hesitation in celebrating him.

His legacy involved the three daughters of a poor father unable to provide the dowries that would save his girls from slavery or prostitution. Mythology wove the detail. Nicholas either tossed three bags of gold through the window or dropped them down the chimney, but the bags fell fortuitously into the girls’ stockings, which were hung up to dry by the fire. Thus was born the tradition of the Christmas stocking, not an English thing at all, but a Dutch import via America. An orange in the stocking toe symbolises those legendary bags of gold.

Father Christmas and Santa Claus became synonymous and children and adults alike soon succumbed to jingle-bells commercialism. By today’s evidence, the US prevailed in the cultural collision. However, in matters of national tradition, we may defer to the National Trust ruling: ‘Santa Claus should be known as Father Christmas in stately homes and historic buildings because the name is more British.’

‘It’s all about wonder and to look, to be able to ponder’ – the story behind spectacular nativity scenes

Each December, a newborn baby takes centre stage in Nativity scenes throughout the land. Julie Harding meets those responsible for

The perennial fascination with snow at Christmas, and how it's all down to Charles Dickens and the Little Ice Age

Snow at Christmas is a rare sight across most of Britain, yet it’s indelibly intertwined in the collective imagination. Felicity

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Curious Questions: Why on earth do we have Christmas trees?

In the middle of winter, we cut down fir trees, bring them inside and decorate them – then let them shed

After some decades in hard news and motoring from a Wensleydale weekly to Fleet Street and sundry magazines and a bit of BBC, Ian Morton directed his full attention to the countryside where his origin and main interests always lay, including a Suffolk hobby farm. A lifelong game shot, wildfowler and stalker, he has contributed to Shooting Times, The Field and especially to Country Life, writing about a range of subjects.