Curious Questions: Is there any future for Encyclopedia Britannica?

Once the first set of books required in any home library, encyclopedias have long since been superseded by the internet. But rather extraordinarily there is still a market for them, as Octavia Pollock finds out.

Not for nothing was the Age of Enlightenment so named. The Encyclopaedia Britannica was born 250 years ago this month out of a desire to be enlightened or, in the case of its creator, Colin Macfarquhar, to enlighten others. With engraver Andrew Bell, he formed a Society of Gentlemen to fulfil his grand idea, citing ‘any man of ordinary parts’ as the intended audience for the book’s 40 ‘treatises’ on the Sciences and Arts. The 127 authors included American Founding Father Benjamin Franklin and philosopher John Locke, although editor William Smellie wrote many essays himself.

The first edition was published in 100 parts from 1768 to 1771, bound into three volumes at £12 each. Such was their success, selling 3,000 copies, that a second edition of 10 volumes appeared between 1777 and 1784. The 14 subsequent editions each broke new ground: the seventh was the first to include an index; the 10th to be produced by editors in New York as well as London; the 11th had 1,700 different contributors, and editions after the First World War included celebrity contributors such as Marie Curie (on radium), Leon Trotsky (in Lenin) and Harry Houdini (on conjuring).

What does the future hold for it now, however? The erstwhile legions of notoriously persistent door-to-door salesmen have been put out of work forever by the internet. Britannica itself made the leap to online-only in 2012 but Wikipedia, with its volunteer army, is the new colossus.

Wikipedia, of course, lacks the battery of experts and editors that lends Britannica its authority, but even the original has occasionally been at fault. In the early 1960s a physicist named Harvey Einbinder wrote a book called The Myth of Britannica poking holes in the errors apparent in dozens of the articles; and as recently as 2005 a 12-year-old boy, Lucian George, discovered mistakes concerning Poland in 2005.

The ease of the internet means the average writer or student will seldom scan the silky-smooth leaves of a bound volume, but there is hope: an edition of Britannica is a snapshot in time, full of information (and people) once deemed important but now long-since edited out, and almost forgotten. ‘We still get requests from authors looking for biographical entries,’ says Hester Vickery of John Sandoe Books, citing one example.

Other uses are more academic. ‘A work such as Britannica is valued less as a source of information than as a landmark work in the history of the collection and dissemination of information,’ says Donovan Rees of antiquarian book dealers Bernard Quaritch. ‘Today, editions tend to be bought by collectors.’

Those collectors often have deep pockets: a fine set of the sixth edition was sold by Bernard Quaritch last year for £10,000 and a first edition made $35,000 at Christie’s New York in 2008, far above its estimate. The first, sixth (with six-volume supplement) and 11th editions tend to be the most prized, together with the rare second edition, of which only 1,500 copies were made.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Yet the collectors have a rival for their bids: interior designers. The beauty of leather-bound volumes gives them a new lease of life as wall dressings. ‘Honestly, 99.9% of the encyclopedias I sell are for decoration,’ says Sasha Poklewski-Koziell of Classic Rare Books. With a full set of the 15th edition taking up more than three yards of shelf space, it’s easy to fill an alcove or two.

To all those who feel that this is a crying shame, consider the alternative: that these beautiful old books instead end up in landfill. Considering the great part they’ve played in satisfying humankind’s thirst for knowledge, that seems a poor fate. And there’s always the hope that those bought for decoration end up being used as intended. After all, a handsome volume is a far more congenial companion for a wet Sunday afternoon by the fire than an iPad.

Credit: Nature Picture Library

The bizarre world of woodlice: 176 crazy nicknames and seven pairs of lungs

The friendly little woodlice with whom you share your garden – and your home – are creatures of extraordinary wonder. Ian Morton's

Credit: Picfair

Mystery solved: Why nature loves the hexagon, and why without it you'd be a puddle of goo

The hexagon abounds in the natural world. John Wright investigates why.

Running a tight ship: 14 facts about the HMY Britannia

For The Queen, the tourist attraction Britannia was once a home away from home. Here are 14 facts about this

The last bicycle maker in the Midlands: 'Our founder wanted small numbers and high quality. We've stuck rigidly to that.'

Tessa Waugh discovers why the company has stayed faithful to the first designs.

Octavia, Country Life's Chief Sub Editor, began her career aged six when she corrected the grammar on a fish-and-chip sign at a country fair. With a degree in History of Art and English from St Andrews University, she ventured to London with trepidation, but swiftly found her spiritual home at Country Life. She ran away to San Francisco in California in 2013, but returned in 2018 and has settled in West Sussex with her miniature poodle Tiffin. Octavia also writes for The Field and Horse & Hound and is never happier than on a horse behind hounds.

-

‘It had the air of an ex-rental, and that’s putting it politely’: How an antique dealer transformed a run-down Georgian house in Chatham Dockyards

‘It had the air of an ex-rental, and that’s putting it politely’: How an antique dealer transformed a run-down Georgian house in Chatham DockyardsAn antique dealer with an eye for colour has rescued an 18th-century house from years of neglect with the help of the team at Mylands.

By Arabella Youens

-

A home cinema, tasteful interiors and 65 acres of private parkland hidden in an unassuming lodge in Kent

A home cinema, tasteful interiors and 65 acres of private parkland hidden in an unassuming lodge in KentNorth Lodge near Tonbridge may seem relatively simple, but there is a lot more than what meets the eye.

By James Fisher

-

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication'The Great Gatsby' sold poorly the year it was published, but, in the following century, it went on to become a cornerstone of world literature.

By Carla Passino

-

Love, sex and death: Our near-universal obsession with the rose

Love, sex and death: Our near-universal obsession with the roseNo flower is more entwined with myth, religion, politics and the human form than the humble rose — and now there's a new coffee table book celebrating them in all of their glory.

By Amy de la Haye

-

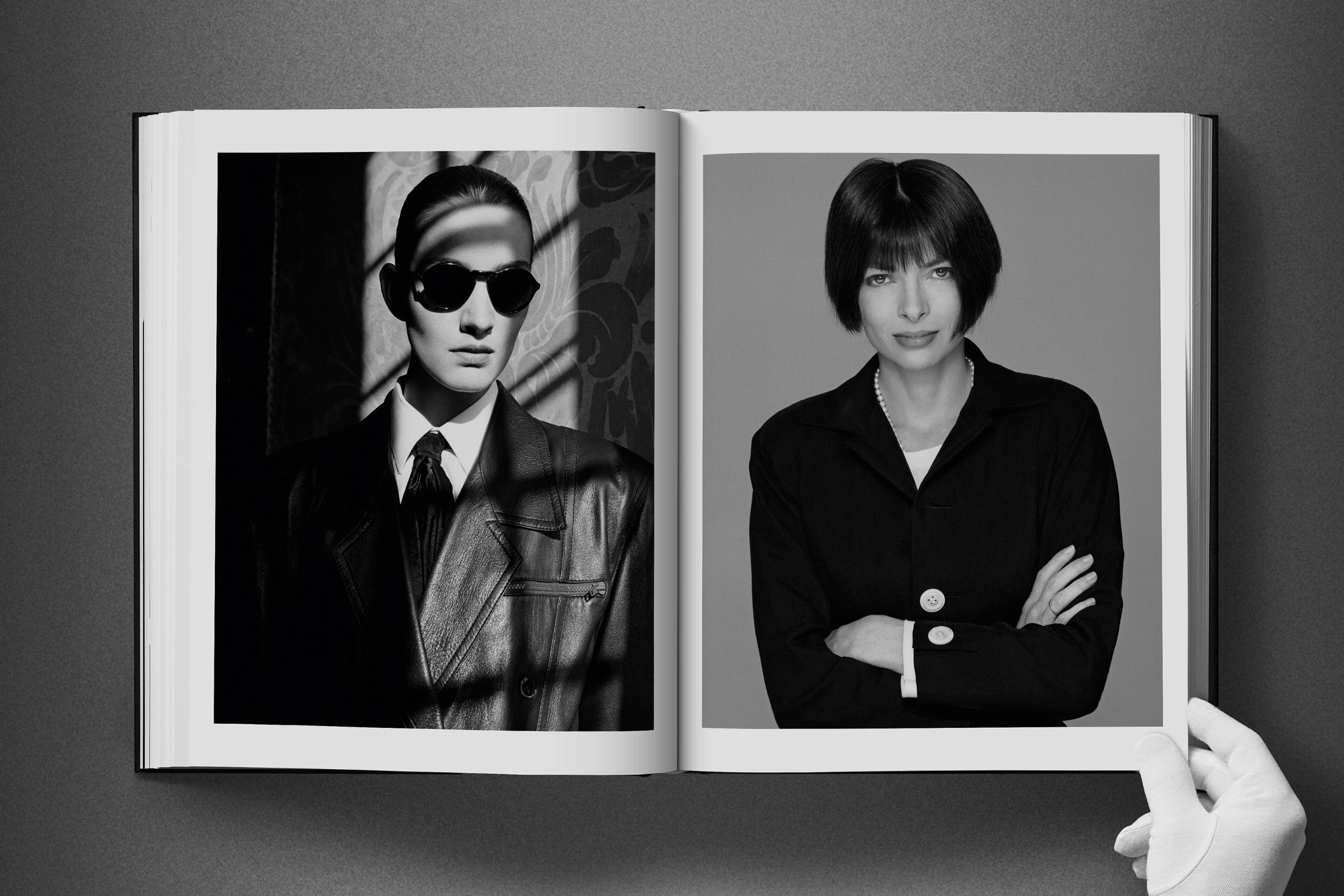

When London was beginning to establish itself as modern cultural powerhouse: The 1980s according to David Bailey

When London was beginning to establish itself as modern cultural powerhouse: The 1980s according to David BaileyIn his new book ‘Eighties Bailey’, ‘era-defining’ photographer David Bailey explores a time when London and the UK were at the centre of the fashion, art and publishing worlds.

By Richard MacKichan

-

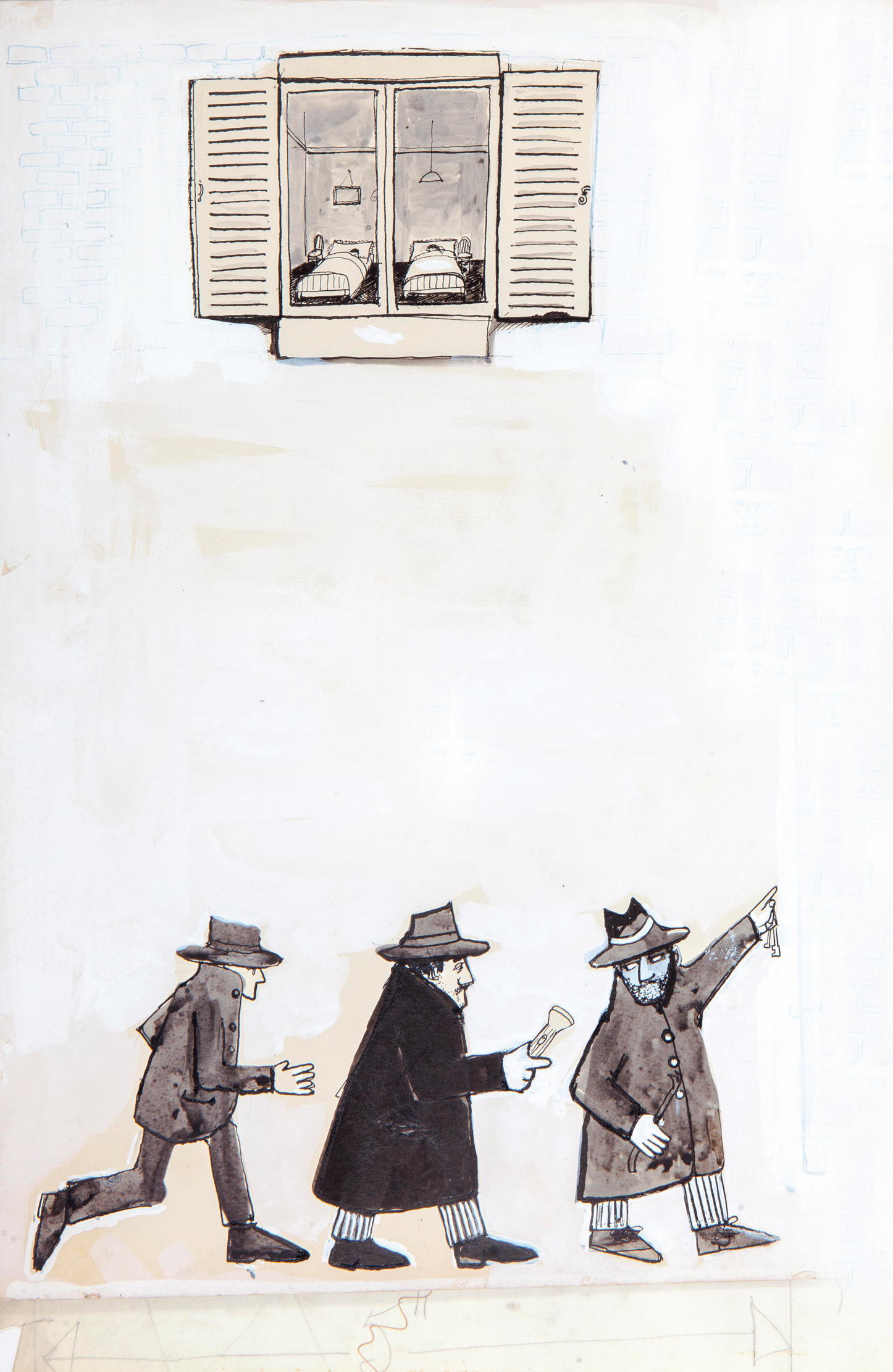

The life and times of P. G. Wodehouse, 50 years on from his death

The life and times of P. G. Wodehouse, 50 years on from his deathBertie Wooster, Jeeves, Lord Emsworth and the Blandings Castle set: P. G. Wodehouse’s creations made him one of the most widely read humorists of the 20th century, but he was denounced as a traitor and a Nazi.

By Roderick Easdale

-

From fighting for stockings to flying on the Moon: How nylon changed the world

From fighting for stockings to flying on the Moon: How nylon changed the worldAlmost 90 years after it was first discovered, Martin Fone looks at the history of this mass produced man-made fibre.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Why do woolly hats have bobbles?

Curious Questions: Why do woolly hats have bobbles?Some can rock a bobble hat, others will always resemble Where’s Wally, but the big question is why the bobbles are there in the first place. Harry Pearson finds out as he celebrates a knitted that creation belongs on every hat rack.

By Harry Pearson

-

The story of how 007 creator Ian Fleming came to write Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang

The story of how 007 creator Ian Fleming came to write Chitty-Chitty-Bang-BangChitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang, our fine four-fendered friend, turns 60 on October 22nd. Mary Miers relives the adventures of the magical flying car and reveals the little-known story of its creation by Ian Fleming, as the writer turned his attention from the world of 007 to a children's tale.

By Mary Miers

-

Curious Questions: We used to fly cars across the English Channel in 20 minutes — why did we stop?

Curious Questions: We used to fly cars across the English Channel in 20 minutes — why did we stop?It seems hard to believe, but taking your car across the English Channel to France by air actually pre-dates the cross-channel car ferry. So how did it fall out of use almost 50 years ago? Martin Fone investigates.

By Martin Fone