The Royal Academy at 250: 'It's like a wonderful Bentley that you discover unused in a barn'

The artist and President of the Royal Academy on its 250th anniversary year.

Elegant in manner, considered in his conversation, Christopher Le Brun is master of the eloquent analogy. ‘It’s like a beautiful car,’ he proffers when I venture that the Royal Academy (RA) seems to be firing on all cylinders. ‘A wonderful Bentley that you discover unused in a barn. You get it out and it’s in perfect working order, but it’s only been used for light shopping; in fact, it needs to be out on the corniche, so I effectively put my foot on the accelerator.’

The man at the wheel is a moderniser, committed to steering his esteemed charge back to its rightful place at the vanguard of the field, yet he’s also deeply reverent of the history and traditions that distinguish this great British institution. ‘It’s got this beautiful structure,’ he says, reminding me that the RA’s constitution pre-dates – and probably influenced – that of America. ‘It holds its two parts – the general assembly and the council – in perfect balance.’

In an organisation entirely run by artists, he sees his job as ‘trying to get consensus’. Contrary to the impression of a body of older men in tweeds sitting around a table smoking pipes (legacy of the RA’s notoriously reactionary era), ‘it’s actually rather wild. Meetings are never, never dull, but very lively and almost impossible to control’.

'It wasn’t a cool thing to do. Then, people such as David Hockney, Allen Jones and Ron Kitaj joined and things started to change.’

As it approaches its 250th birthday, the RA is riding the crest of a wave, with the unveiling of a huge capital project imminent, a slew of outstanding exhibitions under its belt and a new generation of successful Academicians. Mr Le Brun, who was elected in 1996 and became the 26th President in 2011 (the youngest since Lord Leighton), admits that, 30 years ago, when his own work was reaching international acclaim, he wouldn’t have accepted membership.

‘You have to ask yourself “is it good for my career” and, back then, it wasn’t a cool thing to do. Then, people such as David Hockney, Allen Jones and Ron Kitaj joined and things started to change.’

His experience as a trustee of several leading art museums altered his perception. He could see there was a danger of the big, taxpayer-funded institutions becoming the official established position of the art world, the sole preserve of curators and museum professionals.

‘What seemed to be missing was a direct connection between artists and the public. The RA sits between the museum and the commercial art worlds; it can directly address the public.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

'We receive no government money. Zero.'

One reason why its exhibitions are so successful, he believes, is that ‘they’re probably more emotional and aesthetic. When you leave, your mood is different. You don’t so much feel “I’ve learnt something” as “I’ve felt something”.’

Having watched droves of visitors jostling to view the latest blockbuster – Charles I’s collection – I ask how the RA manages to net such exceptional loans. ‘Partly through our connections, but we also rely on the glamour of the galleries and the skills of our curators in forging partnerships.’

How does the RA survive with so much less funding than the other main institutions? ‘Don’t worry me by reminding me,’ he implores. ‘We receive no government money. Zero. We’re a charity; we depend on our friends, supporters, patrons and exhibitions. Most people regard us as an exhibition venue. What’s missing from that view is that we’re an Academy.

‘In other words, we have an art school – the oldest in the country, which remains free and we’re absolutely wedded to that – mostly subsidised by the Summer Exhibition. Plus we have a very special library and a very serious collection, with the only Michelangelo sculpture in this country.’

‘People expect a certain amount of grandeur. There’s that slight sense of scruffy English country house, the smell of wet mackintosh – or dog, at worst. That feeling, I think, is unique.’

Now, as part of the new development connecting Burlington House with Burlington Gardens (opening May 19), that collection will be freely accessible. A huge gallery will be devoted to what is, in effect, a complete survey of British art from 1768, including a great, as yet untapped, body of contemporary works. The inaugural display of the Collection Gallery has been devised by the President himself. ‘Starting with Reynolds, it establishes how we began and whether the principles that sustained us then continue; my contention is that they do.’

Although he hates the words, Mr Le Brun is committed to achieving accessibility without dumbing down. ‘We’re very careful to make art the point of what we do and never politics or social engineering.’ He recognises the importance of preserving the RA’s special character. ‘People expect a certain amount of grandeur. There’s that slight sense of scruffy English country house, the smell of wet mackintosh – or dog, at worst. That feeling, I think, is unique.’

Brought up in Portsmouth in a distinguished military family, he had hardly ever visited London before studying at The Slade. ‘I remember the thrill of walking up the steps of the Royal Academy and preparing myself mentally for an immersion into fine painting.’

Despite the greater pressures of the job today, he believes ‘it’s absolutely essential’ that the president is a practising artist. ‘I do this job for three days in my suit and tie, and occasionally my medal, and then on Thursday, I’m in jeans in my studio.’

The image of the artist as perpetual rebel is, he thinks, superficial. ‘Most of us have several types of potential in our personality. I find something about this job very, very satisfying. It may be my background that makes me think of structures and responsibilities as benign. You make things happen.’

He adds: ‘I like people and I’ve found a way to work with people. At the same time, after a certain amount of that, I need to be completely on my own.’

Christopher Le Brun, seen here with his Painting as Sunrise (2013), will exhibit at the Lisson Gallery, London NW1, from July 4–August 18 (www.lissongallery.com). For more on the New Royal Academy of Arts and its programme of 250th anniversary events, visit www.royalacademy.org.uk/ra250

The charming London rus in urbe once owned by Dame Laura Knight

The first woman to be elected a full member of the Royal Academy lived at 16, Langford Place.

Credit: Getty

Royal Academy artists have decorated ukuleles, and they're being sold off to help a great cause

Some of Britain's finest artists have each painted a ukulele, with the instruments being auctioned off for charity later this

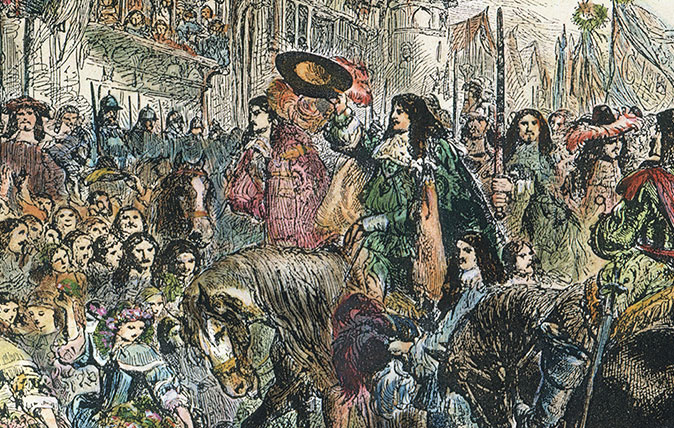

Credit: The Restoration of Charles II - 17th century engraving, Victorian colouring

The fascinating story of the 'lost' royal art collections of Charles I and Charles II

The royal art collections of Charles I and Charles II were scattered across Europe – and after the Restoration, huge efforts

Mary Miers is a hugely experienced writer on art and architecture, and a former Fine Arts Editor of Country Life. Mary joined the team after running Scotland’s Buildings at Risk Register. She lived in 15 different homes across several countries while she was growing up, and for a while commuted to London from Scotland each week. She is also the author of seven books.

-

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country Life

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country LifeWe take a look at some of the best houses to come to the market via Country Life in the past week.

By Toby Keel

-

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwards

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwardsCampaigners in England often point to Scotland as an example of how brilliantly Right to Roam works, but it's not all it's cracked up to be, says Patrick Galbraith.

By Patrick Galbraith