The bagpipe-maker: 'The older customers want me to make their pipes sharpish; they want to be sure they’re not dead before they get to play them!'

Hours of intricate work are needed to craft a set of bagpipes. Kate Lovell spoke to bagpipe-maker Dave Shaw to find out how it's done.

Bagpipes are as much a part of Scottish culture as whisky, the kilt and Nessie, but they’re actually an Ancient Egyptian import thought to have been introduced into Britain by the Romans. Regional variations emerged and it was one of these that, 40 years ago, caught bagpipe-maker Dave Shaw’s eye.

‘I see the process involved in making something and simply get a mania for it. That’s what happened with the bagpipes,’ admits the Co Durham-based craftsman.

There was no childhood connection, either, save for a bagpipe-trilling farming neighbour of his father’s. ‘He would walk up his mile-long drive each evening, practising his bagpipes – even now, it’s an evocative sound.’

Mr Shaw harboured ambitions of becoming a vet, but his failure to secure a place on his chosen course led him to study agricultural botany, then do a number of jobs, including tree-felling. What he really wanted to do, however, was make concertinas.

‘The 1970s folk revival was in full flow and everyone wanted to get into folk music,’ he recalls. ‘Concertinas fascinated me, but, when a friend came back from the British Antarctic Survey with a set of Northumbrian smallpipes he’d found in a house in Port Stanley, I was really taken by them, so we did a swap.’

As the pipes weren’t in good condition, Mr Shaw bought a pipe-making book and used it as his manual. He refurbished the pipes, spent seven hours a day teaching himself to play and then spent the family savings on a second-hand Coronet Major Universal Woodworking Machine, which meant he could make the instruments professionally.

‘It’s a very sizeable piece of equipment and the midwife found it most unusual when she walked through the kitchen on her visit to my wife,’ he adds with a smile. ‘And that was before she saw the small acid bath needed to clean the bagpipe’s metal components.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

At first, Mr Shaw sold his pipes to people he’d met and word of mouth did the rest. Now, he specialises in Northumbrian smallpipes – acoustically similar to the clarinet – Scottish smallpipes, shuttle pipes and Irish uilleann pipes, which sound like an oboe. Each set takes about 15 days to make, spread over the course of many more.

It’s physical work – boring a 4.4mm hole through a 30cm length of wood isn’t easy and a lot can go wrong, so it’s important to be relaxed and focused.

‘I always start with the sticks,’ he explains. ‘I use African blackwood and boxwood, which are strong and tonally good, cut them into lengths, bore the holes, then centre each piece on the bore for turning and carving into the pipes and chanter.’

The pipes (drones) create the unique bagpipe sound and the chanter is used to make the melody. Mr Shaw then embarks on the keywork, ends and brass ferrules, cleaning the metal parts in an acid bath and soldering them into the shapes he needs. ‘It can get quite hot and smelly in my workshop – a mix of metal, leather and oils – but people always tell me how lovely it is,’ he admits.

The bag comes next. Crafted from leather, often covered in another material, it acts as a reservoir of air to sustain the sound as a piper takes breath. Then, it’s the turn of the reeds. ‘The bagpipe is a reed instrument and I make mine from cane I buy from Barcelona. Each set needs four single reeds for the drones and a double reed for the chanter.’

Once everything is complete and the pipes are assembled, they’re ready for shipping.

‘I’ve made pipes for customers as young as teenagers to beyond pension age and I’ve shipped them to clients all over the UK, to Europe, Australia, America and, more recently, China,’ elaborates Mr Shaw.

‘Bagpipe music can resonate with anyone of any age in any country, but, it’s the older ones – 70-plus – who want me to make their pipes sharpish; they want to be sure they’re not dead before they get to play them!’

Dave Shaw plays his bagpipes at Beamish Open Air Museum, Stanley, Co Durham – www.daveshaw.co.uk

Credit: ©Richard Cannon/Country Life Picture Library

The Pigeon Fancier: 'I set up a deckchair in the garden and wait for them to come back. That’s the most exciting part.'

This week’s Living National Treasure is Colin Hill, a pigeon fancier whose birds regularly race from the tip of Scotland

The neon sign maker: 'Piccadilly Circus was our answer to Vegas – now it's all pixellated screens'

This week's Living National Treasure is Marcus Bracey, the man behind the neon signs that light up our cities. He

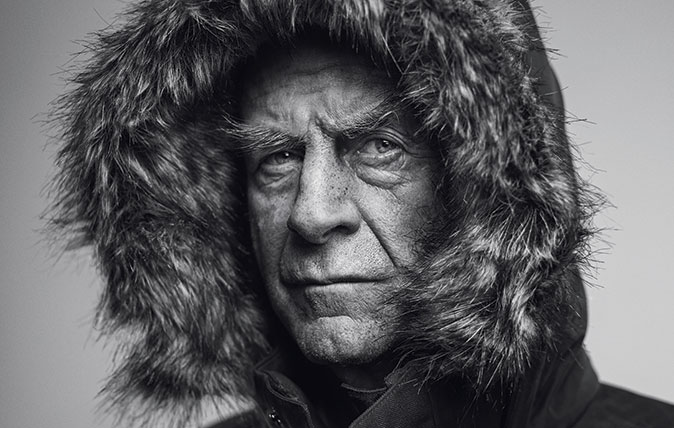

Credit: Sir Ranulph Fiennes (Getty)

Ranulph Fiennes: 'Commuting up and down the motorway is more dangerous than a trip to the Arctic'

Explorer, adventurer and national treasure, Sir Ranulph Fiennes has travelled to the ends of the earth and raised millions for

The Florist: 'What I do is like good cooking – if you have beautiful ingredients, you can’t go wrong'

This week's Living National Treasure is royal florist Shane Connolly – and while he might be based in Britain, he's

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Five beautiful homes, from a barn conversion to an island treasure, as seen in Country Life

Five beautiful homes, from a barn conversion to an island treasure, as seen in Country LifeOur pick of the best homes to come to the market via Country Life in recent days include a wonderful thatched home in Devon and a charming red-brick house with gardens that run down to the water's edge.

By Toby Keel Published

-

Shark tanks, crocodile lagoons, laser defences, and a subterranean shooting gallery — nothing is impossible when making the ultimate garage

Shark tanks, crocodile lagoons, laser defences, and a subterranean shooting gallery — nothing is impossible when making the ultimate garageTo collectors, cars are more than just transport — they are works of art. And the buildings used to store them are starting to resemble galleries.

By Adam Hay-Nicholls Published

-

The 21st century sword maker: 'There’s something appealing about getting metal hot and smacking it with a hammer'

The 21st century sword maker: 'There’s something appealing about getting metal hot and smacking it with a hammer'Practising ancient techniques to craft modern heirlooms, bladesmith Owen Bush handmakes both decorative and practical knives or weaponry, each with their own personalities, says Claire Jackson — with some of his swords celebrities in their own right. Photographs by Richard Cannon for Country Life.

By Claire Jackson Published

-

The secrets of the basket-maker: 'With a basket, you watch it grow before your very eyes'

The secrets of the basket-maker: 'With a basket, you watch it grow before your very eyes'Anna Stickland has woven a new career as a basket-maker; she spoke to Nick Hammond.

By Country Life Published

-

Where I Work: Huw Edwards-Jones, master craftsman and canoe maker

Where I Work: Huw Edwards-Jones, master craftsman and canoe makerThe ups and downs of 2020 didn't see Huw Edwards-Jones change where he worked, but it did change what he did: he's used the time to switch from creating beautiful hand-made furniture to spectacularly beautiful canoes. He spoke to Toby Keel.

By Toby Keel Published

-

In Focus — The Cotswolds silversmith: 'We make beautiful works of art to last for hundreds of years'

In Focus — The Cotswolds silversmith: 'We make beautiful works of art to last for hundreds of years'Tucked away in an old Cotswolds silk mill, expert craftsmen harness a century of expertise to raise, planish and finish fine gold and silverware. Jeremy Flint visits Hart’s of Chipping Campden.

By Country Life Published

-

The master shoemakers who shod Churchill: 'Demand is through the roof, but it takes six to eight months to make a pair'

The master shoemakers who shod Churchill: 'Demand is through the roof, but it takes six to eight months to make a pair'The co-owners of bespoke shoe shop George Cleverley, father and son George Glasgow Snr and George Glasgow Jnr, talk to Hetty Lintell.

By Hetty Lintell Published

-

The dolls' house-maker: 'This is a place to capture the dreams of children and adults alike'

The dolls' house-maker: 'This is a place to capture the dreams of children and adults alike'Dragons of Walton Street have been making beautiful dolls' houses for four decades, and the company is still run by Lucinda Croft, the daughter of the founder. She spoke to Hetty Lintell.

By Hetty Lintell Published

-

Meet the Beadles: The centuries-old private police force at Burlington Arcade, the world's swishest shopping mall

Meet the Beadles: The centuries-old private police force at Burlington Arcade, the world's swishest shopping mallThis week marked the 200th birthday of London’s Burlington Arcade. Adam Hay-Nicholls goes undercover with the Beadles, its private police force. With photographs by Richard Cannon.

By Country Life Published

-

The willow weaver: 'I like to let the host structure feed the form'

The willow weaver: 'I like to let the host structure feed the form'With such romantic names as Dicky Meadows, Flanders Red and Noir de Verlaine, willow is one of Nature’s most versatile materials. Jane Wheatley meet Laura Ellen Bacon, who crafts works of art from twisted stems of Salix.

By Country Life Published