What lies beneath: The weird and wonderful things lurking in Britain's museum basements

From radioactive rocks to great white sharks, and a dolphin called Boris, the things stored in Britain's museum basements make the mind boggle — and now plans are afoot to improve visitor access.

Relocating is tiresome at the best of times, but the sale of Blythe House in West Kensington, the V&A’s primary storage facility since 1984, and home to more than 600,000 objects and books, posed a herculean challenge: 579 truck journeys, to be precise, and a painstaking programme of auditing and conservation treatments.

But out of adversity comes opportunity, and on May 31, the museum’s new game-changing facility, V&A East Storehouse, opens in Stratford in East London supplying 16,000m2 of storage. The difference, this time, is that the storage doors are wide open to the public. The Storehouse’s glassy interior is a metaphor for its mission, offering, say the architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro, ‘unprecedented access and greater transparency, breaking down physical barriers and removing glass cases to get visitors closer than ever before to their national collections’.

‘Throughout Storehouse, you can see every part of Storehouse,’ underlines Kate Parsons, the V&A’s Director of Collections, Care and Access. ‘Objects are beneath you, around you, under you...’ Additionally, the ‘Order an Object’ service, ‘at a scale not possible anywhere else in the world’, means — she explains — that anybody can get up close to a stored item of their choice, from the opulent large rolled textiles craned out of Blythe House to the 12-inch platform heels that toppled Naomi Campbell on the Vivienne Westwood runway.

Turner's 'Dido building Carthage' and 'Sun Rising through Vapour' hang in Room 36 of the National Gallery, next to two paintings by Claude — as requested by the 18th century artist in his will.

Bulging basements are a constant challenge for museums. J.M.W. Turner’s bequest to the National Gallery, the largest donation of artworks in the museum’s 200-year history, was so vast that, for a time, his priceless legacy was left languishing in the museum’s basement. Most of the 300 oil paintings, 30,000 sketches and watercolours and 300 sketchbooks are now located at Tate Britain, which has dedicated nine rooms to Turner’s incredible oeuvre.

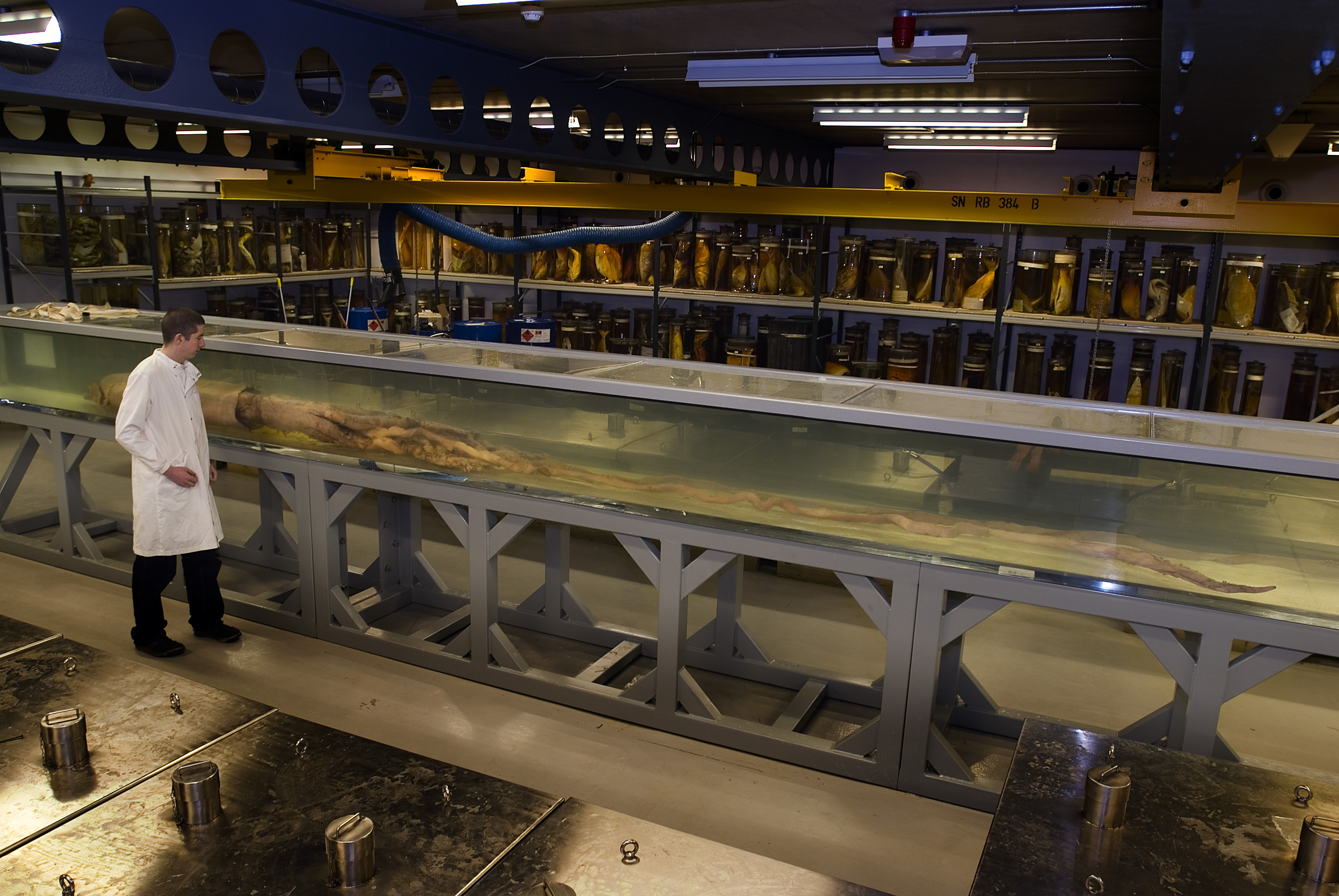

The Natural History Museum is also reassessing its storage to improve research access to its important collection, with plans to open an additional facility at the University of Reading’s Thames Valley Science Park in 2031. The move will free up more gallery space within its beautiful Romanesque building, whose basement storage resembles, in parts, a mad scientist’s lair. A nightmarish collection of around 20 million pickled specimens is suspended in time in the eerie Spirit Collection room, which runs daily tours. Lifting the lid on the largest tanks reveals some formidable residents: two great white sharks, for example, and ‘Archie’, a mythical-sized giant squid measuring more than eight metres long (above).

Sometimes accessing stored collections just requires a little know-how. On the fourth floor of the British Museum, for example, behind a huge Michelangelo cartoon, lies the entrance to the museum’s Prints and Drawings study room. If something in the collection’s two million prints or 50,000 drawings piques a visitor’s interest, an online appointment will grant them a private audience there.

Access to our national treasures is more inclusive than ever before and concepts such as V&A East Storehouse are a beacon for what is possible. ‘You don’t need a reason why you might want to access the collection,’ stresses Parsons. ‘It could just be because you like it, or you want to look at something that makes you happy. It’s on your terms.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The National Museums of Scotland

A short walk from the Firth of Forth’s southern shore is a cluster of buildings that Dr Sam Alberti, Director of Collections for National Museums Scotland, describes as his ‘happy place’: the National Museums Collection Centre in Granton, Edinburgh. Accommodating more than 12 million objects and specimens, the centre contains an estimated 99.8% of the museums’ combined collections, which range from vintage motorbikes to Iron Age horse armour.

Though most artefacts are not currently on display or on loan, ‘there’s a steady flow of people coming to access the collections’, explains Alberti, from international researchers to members of the public who’ve made it onto their oversubscribed tours. ‘These are active places,’ he stresses. ‘They are no longer dusty vaults.’

One of his favourite spaces is the Whale Room (above), with its ‘particularly evocative’ aroma. ‘Whalebone continues to ooze out oil for years afterwards…and it has this amazing smell,’ he effuses. ‘We have 4,000 different cetaceans which have washed up on Scottish shores. They tell an amazing story about the seas around us.’ Among Alberti’s most beloved residents is Boris the bottlenose dolphin, a notorious salmon thief who would break into fish farms, and whose stomach contents revealed that he kept up his wily ways until his dying day despite having ‘only about three teeth left’.

Some of Dr Alberti’s favourite curios evade categorisation, such as the drawers full of strange neolithic stone spheres, about the size of a tennis ball, that, despite decades of research, still mystify the museum. ‘It’s that sense of reveal when you open a door, or pull out a drawer,’ he marvels. ‘There’s always something new.’

Bristol Museum and Art Gallery

Behind the Edwardian Baroque façade of this 200-year-old museum lie three floors of extraordinary exhibits, from Egyptian mummies to paintings by Gainsborough and Constable. ‘The tip of the iceberg is what’s on display, but actually, there’s a whole lot of activity in our [stored] collections at any given time,’ says the museum’s director, Philip Walker, who oversees a portfolio of six institutions.

More than 12 miles (about 20km) of archival records — some sealed with wax or written on vellum — are stored in the nearby harbour, but much of the world-recognised connection lies beneath visitors’ feet, in the museum’s enormous basement. Surprising dangers lurk below, such as rare examples of radioactive rocks, or creatures with razor-sharp jaws.

Deadly Doris wreaked havoc in Wiltshire some 150 millions year ago.

One of the largest and oldest artefacts, nicknamed Deadly Doris, is a case in point. Discovered in Wiltshire in 1994, the eight-metre long, 150 million-year-old, Pliosaurus skeleton is a favourite of Walker’s. Displayed briefly in 2017, she normally resides beneath the museum, while a life-size replica, complete with terrifying teeth, looms fearsomely above visitors to the rear hall.

Some of the contemporary items are also sensational — but for different reasons. For its first 26 series, the BBC medical drama Casualty was filmed in Bristol, and some of its more unusual props have found their way into the city’s storage spaces. Walker is particularly fond of an uncannily realistic severed hand. ‘It’s quite gruesome,’ he admits. ‘But quite fun.’

The Sainsbury Centre, Norwich

Despite its futuristic architecture, designed by Lord Norman Foster in the 1970s at the behest of Sir Robert and Lady Sainsbury, this art museum’s collection includes material culture dating back to 3000 BC. Before its redevelopment in the 1990s, the Sainsbury Centre was a trailblazer in open storage. Even now, a generous 15% of the collection is exhibited, with an additional 5% on loan. ‘We rotate things quite a lot,’ says director Jago Cooper, who estimates that 90% of the museum’s treasures have been displayed at some point.

The rest is underground, with works from all walks of life rubbing shoulders. ‘Often things that are down there are juxtaposed and in really interesting conversations,’ reveals Cooper. ‘So you’ll have a Picasso painting opposite a Polynesian fish hook.’ Accidentally stumbling on John Davies’s human head sculpture from 1973 (above), with its creepy clam-shell mask, is probably the facility’s most terrifying encounter, maintains Cooper, while perhaps the most peculiar is a series of giant resin thumbs — some wearing nail polish — created by the French sculptor César.

This deliberately random organisation also applies to the museum’s Meet the Art search portal which throws up interesting combinations and ‘feels like you are exploring the stores’. ‘The digital world creates multiple ways that you can access collections in really interesting ways,’ enthuses Cooper. Last year, 60,000 users worldwide used the Smartify app to explore their collection through audio tours, interviews and music. ‘It’s brilliant that museums are coming up with new innovations about how people can access them,’ he says.

Deborah Nicholls-Lee is a freelance feature writer who swapped a career in secondary education for journalism during a 14-year stint in Amsterdam. There, she wrote travel stories for The Times, The Guardian and The Independent; created commercial copy; and produced features on culture and society for a national news site. Now back in the British countryside, she is a regular contributor for BBC Culture, Sussex Life Magazine, and, of course, Country Life, in whose pages she shares her enthusiasm for Nature, history and art.

-

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the fun

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the funFrom November, the Ford Focus will be no more. We say goodbye to the ultimate boy racer.

By Matthew MacConnell

-

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric village

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric villageA romantic experiment surrounded by the natural majesty of North Wales, Portmeirion began life as an oddity, but has evolved into an architectural phenomenon kept alive by dedication.

By Ben Lerwill

-

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the fun

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the funFrom November, the Ford Focus will be no more. We say goodbye to the ultimate boy racer.

By Matthew MacConnell

-

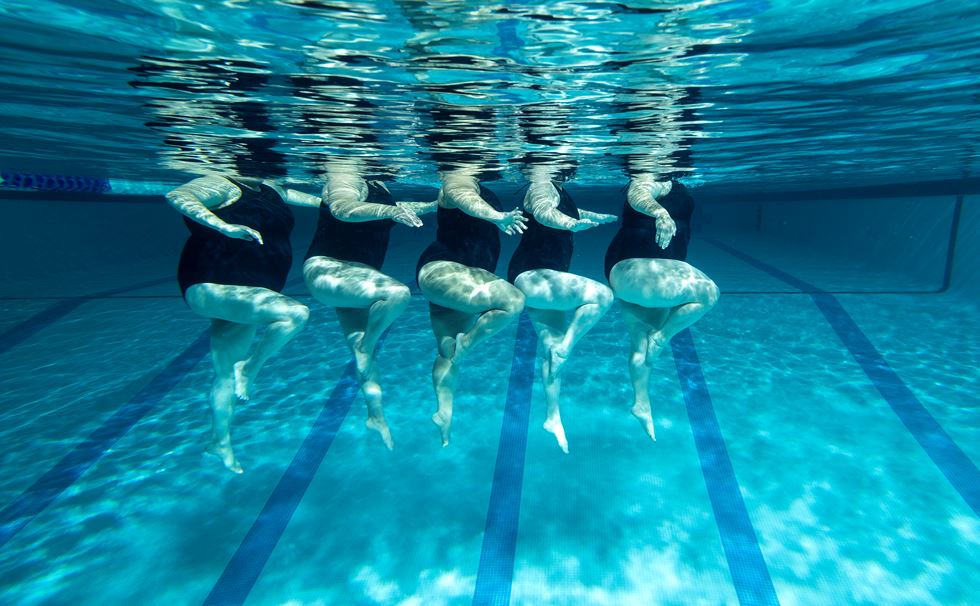

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead Heath

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead HeathEmma Hughes dives into swimming's hidden depths at the Design Museum's exhibit in London.

By Emma Hughes

-

Diamonds are everyone's best friend: The enduring appeal of one of Nature's sparkliest treasures

Diamonds are everyone's best friend: The enduring appeal of one of Nature's sparkliest treasuresEvery diamond has a story to tell and each of us deserves to fall in love with one.

By Jonathan Self

-

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old Masters

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old MastersThe younger generations’ appetite for everything vintage bodes well for the future, says Huon Mallalieu, at a time when an extraordinary Old Masters collection is about to go under the hammer.

By Huon Mallalieu

-

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication'The Great Gatsby' sold poorly the year it was published, but, in the following century, it went on to become a cornerstone of world literature.

By Carla Passino

-

Shark tanks, crocodile lagoons, laser defences, and a subterranean shooting gallery — nothing is impossible when making the ultimate garage

Shark tanks, crocodile lagoons, laser defences, and a subterranean shooting gallery — nothing is impossible when making the ultimate garageTo collectors, cars are more than just transport — they are works of art. And the buildings used to store them are starting to resemble galleries.

By Adam Hay-Nicholls

-

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of spring

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of springThe biggest-ever David Hockney show has opened inside the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris — in time for the season that the artist has become synonymous with.

By Amy Serafin

-

Under the hammer: A pair of Van Cleef & Arpels earrings with an intriguing connection to Princess Grace of Monaco

Under the hammer: A pair of Van Cleef & Arpels earrings with an intriguing connection to Princess Grace of MonacoA pair of platinum, pearl and diamond earrings of the same design, maker and period as those commissioned for Grace Kelly’s wedding head to auction.

By Rosie Paterson