Victor Hugo, France's greatest novelist, was also a talented artist — and now his 'rarely seen' illustrations are on display at the RA

Victor Hugo dismissed his drawings as mere things made in the margins of his manuscripts Now, a Royal Academy exhibition reveals how powerfully they engage the imagination.

A colossal toadstool towers above a drab landscape, at once ominous and lonely, its red cap the only hint of colour in a sea of brown, as an almost human face peeks from its stem. It would look at home among Surrealist paintings, but this 1850 drawing (below) pre-dates the movement by more than half a century and wasn’t even made by a professional artist: instead, it is the work of one of literature’s giants, Victor Hugo. ‘No one really knows what the meaning of this drawing could be, but it has a prophetic, apocalyptic feel about it,’ says art historian and Royal Academy (RA) curator Sarah Lea.

Mushroom is one of some 70 works by the French author to go on display at the RA’s Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo, which Lea curated. ‘It's a long overdue exhibition. The last major [one] in the UK was in 1974. [Hugo’s] drawings are very rarely seen because they are extremely fragile to light exposure and, therefore, I don't think that many people here know this great titan of 19th-century literature was also a visual artist.’

At first, Hugo drew for his children — little sketches of characters from the stories he made up for them, which he left on their bed at night for them to find when they awoke — and his friends, for whom he most drew caricatures. However, explains Lea, ‘the catalyst for him becoming an artist was when he went on trips along the Rhineland and to the Pyrenees, making notations of interesting architecture, a great passion of his. He began a kind of observational drawing as part of his travel writing’. Art became a solace after his beloved daughter Léopoldine drowned in a boating accident in 1843 and, later, during the troubled times leading to the coup d’état by Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte. It was then that, having distanced himself from his own party over his campaign to end poverty, he drew his enigmatic mushroom. ‘He played on the power of abstraction and suggestion, even in drawings that are figurative and representational, to engage our imaginations.’

In 1851, having called the new emperor a traitor to France, Hugo had to flee Paris, initially heading for Belgium, then Jersey and Guernsey, where he published some of his greatest novels, including Les Misérables. ‘His life was defined by this period,’ says Lea, who explains that even after there was an amnesty for political exiles, he wouldn’t return to France as long as Napoleon III’s regime held. It was in Guernsey, specifically at the Lookout (now often called the Crystal Room), the extraordinary glazed room he built at Hauteville House, his home on the island, that he not only wrote extensively, but also made an astounding number of drawings, embracing what became the biggest motif of his work and life: the ocean. ‘I write at my window, I watch the flow being born, expiring, reborn, and the gulls cutting through the air,’ he noted. ‘The ships in the wind open their wingspans, and look in the distance like large figures strolling on the sea.’ When on the island, Hugo — a man of great faith who didn’t support the church as an institution — ‘developed a kind of syncretic religious outlook on life, in that he adopted aspects of Eastern and Western thought and this influenced his view of Nature. He didn't see humans as separate from the wider world,’ explains Lea, mentioning a sketch in which he imagines a ragpicker of the stars, looking down at the Earth. ‘The scales of time and space that he's thinking of is so enormous.’

He also embraced unusual materials — soaking lace in ink to make an imprint, or scraping away the surface of paper to produce highlights, which gave his drawings an element of physicality — and unconventional techniques, some of which were linked to his interest in spiritualism (during his years in Jersey, between 1853 and 1855, he and his family had participated in seances).That, believes Lea, was a spur for some of the semi-automatic processes — art made without conscious control — that he used. For Hugo, ‘drawing is another metaphorical space that he can explore similar themes that he does in his literature, but in a much more fluid way, and he ranges in his processes from very, very detailed fine pencil drawings to virtually entirely abstract, very inky blot like works that really engage our powers of suggestion’.

Nonetheless, the French author dismissed his own works as ‘these things people insist on calling my drawings’, ‘made in the margins or on the covers of manuscripts during hours of almost unconscious reverie’, and never exhibited them, although some were published as prints (the proceeds went to support poor families in Guernsey). The first public exhibition was held in 1888, three years after his death, but Vincent van Gogh had already come across some of the French author’s art in 1880: ‘I’ve seen drawings of Gothic architecture by V. Hugo. Well, without having [Charles] Meryon's powerful and masterly execution, there was something of the same sentiment. What is this sentiment? It has some kinship with that which Albrecht Dürer expressed in his Melancholy.’ Ten years later, he wrote to his brother Theo about some ‘admirable drawings by Vierge, which were just like Victor Hugo's, astonishing things’ — from which comes the RA’s exhibition title.

For Lea, there are parallels between the author of Les Misérables and the Dutch painter: ‘Both had this idea that an artist or a writer could have a creative kinship with people across time and place. For both of them, writing and drawing are so closely tied: Vincent is writing letters every day and when he looks at a landscape or a scene, he might think of a verbal description. Conversely, making a picture would inspire Hugo maybe to write a passage, so there it's a kind of symbiotic relationship.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

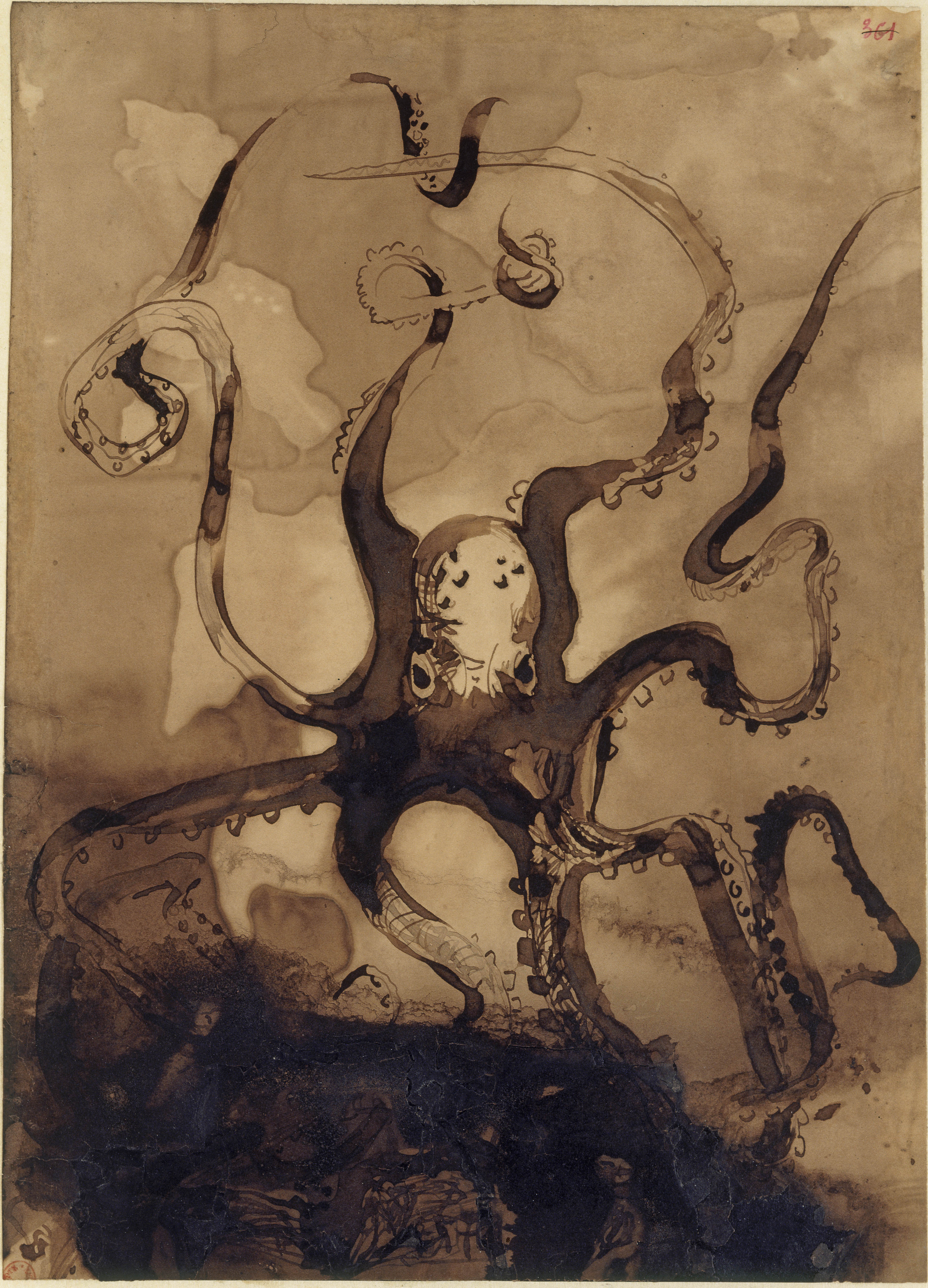

Victor Hugo's 'Octopus' from 1866–69

Although the French author’s works are ‘very much the drawings of a writer, what's interesting about them is that they are not generally illustrative. They're much more creative, the kind of sketches that would help him to ignite his imagination’. His two worlds came together in The Toilers of the Sea: Hugo interleaved his personal manuscript with his drawings of the ocean and although the 1869 edition of the book had illustrations by François Chifflart, later versions featured the author’s own images. Toilers tells the story of a Guernsey boy, Gilliatt, who faces the stormy sea and a giant octopus to retrieve the engine from a wrecked ship and win the love of the shipowner’s niece, Déruchette. ‘We have the fantastic octopus [on display] and if you look quite carefully at the top, the tentacles are entwined, and they form a V and an H.’

Although the RA exhibition is very much about Hugo’s art, Lea hopes it will spark a wider interest in the man and what he believed in. ‘Some of his ideas really were prophetic: he imagined the United States of Europe very early in the 19th century. One of his earliest novels was The Last Day of a Condemned Man, which is a plea against capital punishment. He campaigned for abolition [of slavery], he campaigned for secular education, he campaigned for universal suffrage.’

After returning to Paris in 1870, he and his grandchildren — his sons and daughters had all tragically died — became the Third Republic's royalty so much that, says Lea, ‘for his 80th birthday, all schoolchildren had their punishments cancelled’. When he died, his funeral was attended by some 200 international delegations and ‘double the population of Paris’. He had been a poet, playwright, novelist, politician, artist and (despite a certain blindness towards colonialism) an indefatigable humanitarian campaigner. No poisonous toadstool, he.

‘Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo’ is at the Royal Academy until June 29.

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.