The V&A's Ocean Liners exhibition: A fascinating glimpse into an age of glamour

The fabulous design of the great ocean-going liners had a far-reaching cultural impact associated with national politics and pride, discovers Clive Aslet.

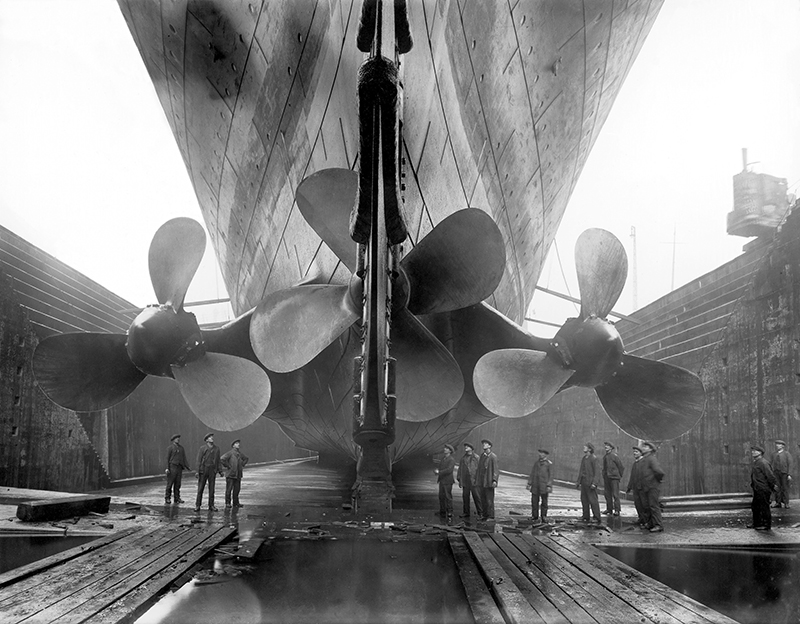

When Charles Dickens first crossed the Atlantic in 1842, he had a miserable time. His state room was an ‘utterly impracticable, thoroughly hopeless, and profoundly preposterous box’ in which he was seasick and fearful during heavy seas. That was before the days of the screw propeller: by the end of the century, ships were larger, faster and on the way to becoming the floating palaces of the first half of the 20th century.

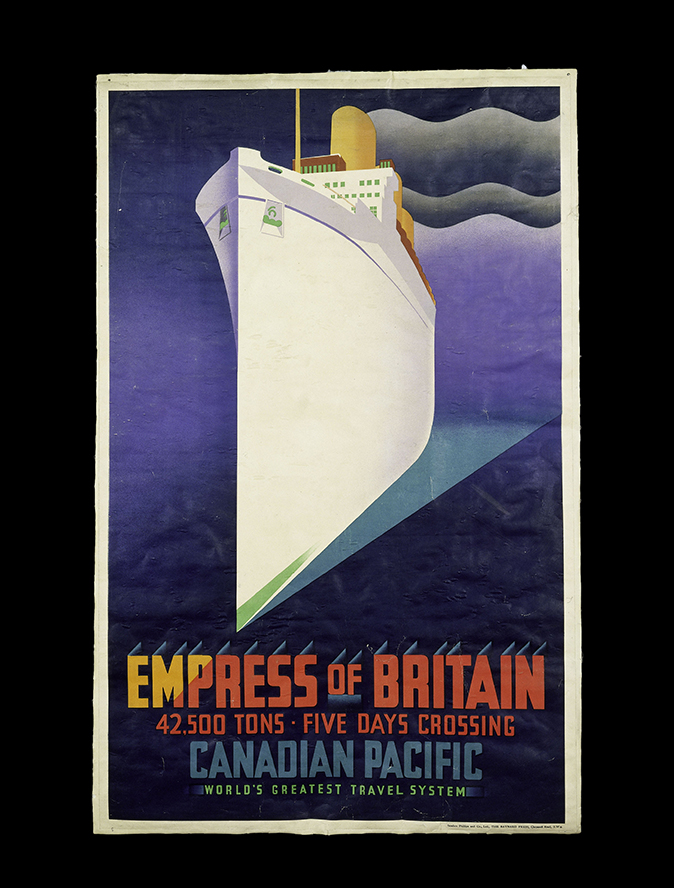

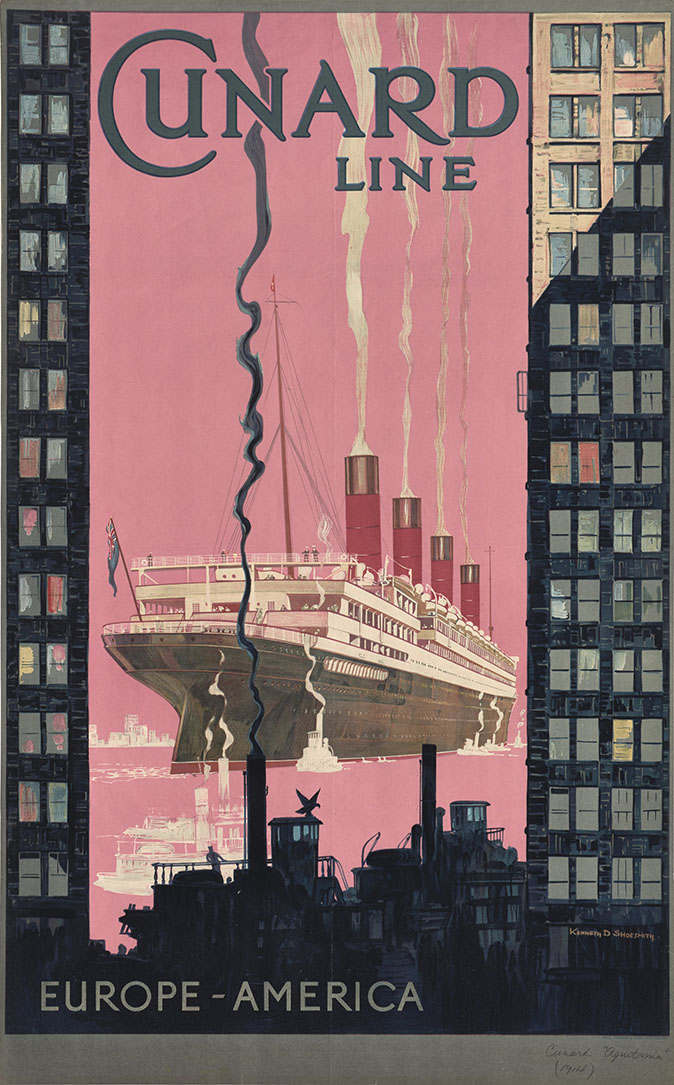

The V&A’s glamorous exhibition explores this heyday, less in terms of the social microcosm found on board (our eyes aren’t offended by the bleakness of steerage) than about style, in all its forms. Shipping companies were highly design-conscious – and competitive.

In an era of intense patriotism, liners expressed national pride. In France and Germany, they were almost national efforts – the French government underwrote Normandie, whose fabulous Art Deco interiors are evoked here through one of the gleaming, gold-coloured panels from the First Class saloon. During the First World War, they would be pressed into service as troop ships, their speed being used not to win the Blue Riband, but to outrun enemy submarines.

Even in 1902, passengers in the smoking room of the Kronprinz Wilhelm should have had an intimation of where things were heading from the painting of a naked youth holding aloft the German flag as he strides through the waves behind two horses: the title, Our Future Lies Upon the Water, is a quotation from the Kaiser.

It was easy to think of other things in the atmosphere of dolce fa niente cultivated among passengers who could do nothing except enjoy the luxury of their surroundings (mal de mer permitting). As a book displayed at the opening of the show declares: ‘Life aboard ship is a little world between two worlds… a week of existence suddenly cast adrift – suddenly freed from every burden, every aggravation of life ashore… It is… it should be… an enchanted week.’

Before 1910, the object was reassurance: passengers on most ships moved between interiors of different historical styles much as they would have done in a smart country house or hotel. The largest surviving fragment from Titanic is a carved panel from the First Class lounge, shown as if floating on the sea, as it was found; the Louis XVI style is that of The Ritz.

It was left to the German Norddeutscher Lloyd to employ the Jugendstil architect Bruno Paul, but gradually it dawned, even on stylistic conservatives, that liners were different: they provided design opportunities unlike those on shore.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

One example of this was the grande descente: a sweeping staircase of parade, whose purpose was to show off fashionable women in beautiful dresses as they came down it. The idea preceded the Busby Berkeley spectacular, but had something in common with it – although, as in a Court masque, the participants were not showgirls and professional dancers, but members of the audience. Art Deco – French and flashy – was the style most obviously suited to such display.

The British preferred exotic woods from the colonies, as seen on the Queen Mary: somewhat sober by comparison. To Le Corbusier, the liner was a symbol of Modernism – although he didn’t care much for the decor of those he travelled by, preferring to photograph funnels and engine rooms. (In similar vein, his favourite entertainment was the Punch and Judy show and his best friend on board was the PT instructor who gave him a 7am workout every morning – ‘a terrific chap’.)

The Orient Line was one of the few inter-World War lines to match a Machine Age aesthetic to its vast, ocean-going machines: it employed the New Zealander Brian O’Rorke to create what the catalogue calls ‘an integrated approach to modern ship design’. The pared-down aesthetic triumphed after the Second World War, partly in response to the large number of ships lost to fire.

How far did ship design influence developments on land? Modernists felt they should do: passengers who accepted cramped sleeping quarters because their waking time was spent in generously proportioned shared spaces should have been prepared to pool their resources in Socialistic schemes ashore (they weren’t).

However, for many passengers, an up-to-date state room, with adjacent bathroom, would have represented a considerable advance on the amenities of their ancestral country house. It must have made them impatient to update their antediluvian piles, while habituating them, in London, to life in a flat.

‘Ocean Liners: Speed and Style’ is at the V&A, Cromwell Road, London SW7, until June 17 find out more at www.vam.ac.uk