‘To grasp the momentousness of the reopening, one must understand the place The Frick holds in the hearts of New Yorkers’: Inside the splendour of Fifth Avenue’s beloved gallery

The beloved NYC art museum’s ‘renovation and enhancement project’ manages to both assure and astonish.

A decade of planning. Five years of heavy work. $220 million spent. The Frick Collection’s recently completed ‘renovation and enhancement project’ is the most comprehensive refresh in its 90-year history, and it’s being unveiled to the public this month. As Country Life’s New York correspondent, I’ve been given a preview, and can say that well-enough has been left alone, and, well, not well-enough has been made right. Spectacularly so.

To grasp the momentousness of the reopening, one must understand the place The Frick holds in the hearts of New Yorkers, and, indeed, art-lovers around the world. The Frick is based in an Upper East Side Gilded Age mansion, built for industrialist Henry Clay Frick in 1914; in 1935, it opened as a museum for his family’s art holdings, which comprise one of the great private collections of Old Masters and decorative arts. So while The Frick is clearly among America’s premier art institutions, its compact size and the fact that you’re essentially in someone’s house makes it feel like you’re in on a secret. Further up Fifth Avenue, The Met dazzles with its sheer scale; you will never get through it all, no matter how many visits. The Frick, meanwhile, is of an afternoon. You pop in to see a special exhibit of European works on paper, to check in on Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert. You take your in-laws when they’re in town. In short, it’s a gem, and that gem has been polished.

The Frick's 70th Street Entrance.

The Oval Room.

Call me a Frick partisan; I have visited often. Bury me between the two monumental Turners hung opposite each other in the West Gallery, the luminescent portscapes Dieppe and Cologne. I’ve been to The Frick on dates (‘Want to see a Meissen porcelain exhibit?’ being a good filter). I’ve paid visits specifically to a piece of its furniture, the Jean-Henri Riesener commode in the South Hall, for a paper I wrote on it in interior design school. During the pandemic, I held to its ‘Cocktails with a Curator’ series as a cultural lifeline in the otherwise artless bleakness. I went more than once to see the collection when it was moved, during the renovation, to the Breuer-designed former Whitney building on Madison Avenue; viewing the Gainsboroughs, Titians and Whistlers against the cold Brutalist walls was revelatory.

At the new Frick, some things are different — thrillingly so. But first, what’s the same. Think of the moments in The Frick you know and love — standing between those Turners, or staring up at the terracotta Diana the Huntress in the Portico Gallery — and rest assured they remain the same. (Just-retired director Ian Wardropper says you might even wonder, Well, what did they change?) That’s not to say those parts of the museum haven’t been improved — in fact virtually nothing in them has been left untouched. The silk wall hangings have been replaced, the ceiling carvings meticulously restored. (Less glamorously, the heating and cooling, lighting and electrical systems updated.) The number of best-in-their-field artisans, craftspeople, designers and engineers involved in the effort boggles the mind; see the excellent Renovation Stories for a look at how, say, the museum had its passementerie recreated by the same French firm that produced the originals over a century ago.

But enough about the renovating piece of the project; onto the enhancing. Here are three major upgrades to look forward to during your next visit:

You can now access the upper floor

Henry Clay Frick and his wife, photographed in c.1900.

The Frick family’s former private rooms on the (American) second floor have been converted to galleries for smaller-scale paintings, sculptures and objects that previously would have been shown in the larger rooms on the main floor — the scale of the smaller upstairs rooms is more sympathetic — or not shown at all.

When limited to the main floor, you lacked a complete sense of how the house functioned; rather, you stood at the foot of the original Grand Staircase, behind a velvet rope, wondering what was up there. (Staff offices.) Now, ascend to see the Breakfast Room hung as it was for the family, with the contemporary Barbizon landscapes Frick collected before he moved onto Old Masters.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In Frick’s walnut-panelled bedroom, George Romney’s Lady Hamilton, which had been on display downstairs, is back over the mantel; the picture is presumed to be the last artwork Frick viewed, having died in bed across from it. The bedroom of Frick’s daughter, Helen Clay Frick, features Renaissance gold-ground panels, a testament to her role in shaping the family’s collection. The Boucher Room (above), named for its painted panels and filled with 18th century French furniture, has been moved from its prior location on the main floor back to its original setting upstairs. The Impressionist Room shows works by Manet, Monet and Degas, while other rooms are given over to French faience, Du Paquier porcelain, rare portrait medals, and important clocks and watches.

The result of the expansion? The number of works on view has doubled.

Special exhibition spaces on the main floor

In addition to its permanent holdings, The Frick is prized for its tightly focused, intellectually rigorous special exhibitions. Now there’s a dedicated space for them. (Before, the museum had to put away pieces from its collection to make room for the temporary hang — not ideal.)

Inaugurating the new suite of galleries is the three-work exhibit Vermeer’s Love Letters, opening in June, which explores Vermeer’s treatment of the theme of letters and his depiction of women of different social classes.

Additionally, the intimate Cabinet Gallery has been newly dedicated to special shows. Coinciding with the reopening is Highlights of Drawings, featuring Degas, Goya and Rubens. In the autumn, there’s work by the contemporary British painter Flora Yukhnovich, who’s creating site-specific murals inspired by The Frick’s Boucher masterpiece Four Seasons.

New amenities dazzle

The showstopping moment of the reopening comes early in your visit: Step in from East 70th Street into a greatly expanded Entrance Hall (above) that’s now airy and bright, positively Milanese in its sleekness. At the preview, many a finger was pointed and jaw dropped at the new cantilevered stairway in the back, all brass and glass and Breccia Aurora marble. The new amenities collectively speak to The Frick’s commitment to go on showing its collection for another 90 years, and to playing a revitalised role in New York cultural life more broadly.

There’s a bright new conservation room, and The Frick now has its first education centre. A new auditorium (above) has been built underground, which required digging up the 70th Street Garden (designed by Russell Page in 1977) and replanting it. With seating for 220, the circular, white-walled auditorium is another modern counterpoint to the robber-baron chic of the main galleries.

A Spring Music Festival kicks off the reopening and includes the world premiere of a work by Nico Muhly, performed by the Jupiter Ensemble and current alt-opera darling Anthony Roth Costanzo.

The highly regarded Frick Art Research Library has been connected to the museum via passageway — before you had to walk around the block to get to it, if you even knew it was there. On the exterior, the construction allowing for this and other additions has been clad with the same Indiana limestone, in the same block pattern, as the original Beaux-Arts buildings, highlighting the renovation’s painstaking historical sensitivity. The project was designed by Selldorf Architects (who at the National Gallery, London, has been leading the renovation of the Sainsbury Wing), with Beyer Blinder Belle as executive architect.

And finally, The Frick now has what it perhaps was most sorely missing: a café.

The Medals Room.

The Living Hall.

The Garden Court.

The grand staircase.

The Portico Gallery.

The Frick Collection reopens to the public on April 17, 2025. Visit the website for more information.

Owen is Country Life’s New York arts and culture correspondent. Having studied at the New York School of Interior Design, his previous work includes writing and styling for House Beautiful and creating watercolour renderings for A-list designers. He is an unreconstructed Anglophile and has never missed a Drake’s archive sale.

-

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagne

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagneAn upwardly mobile spaghetti Bolognese, lasagne al forno, with oozing béchamel and layered meaty magnificence, is a bona fide comfort classic, declares Tom Parker Bowles.

By Tom Parker Bowles

-

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025Thursday's Quiz of the Day asks exactly how popular Baywatch became.

By Toby Keel

-

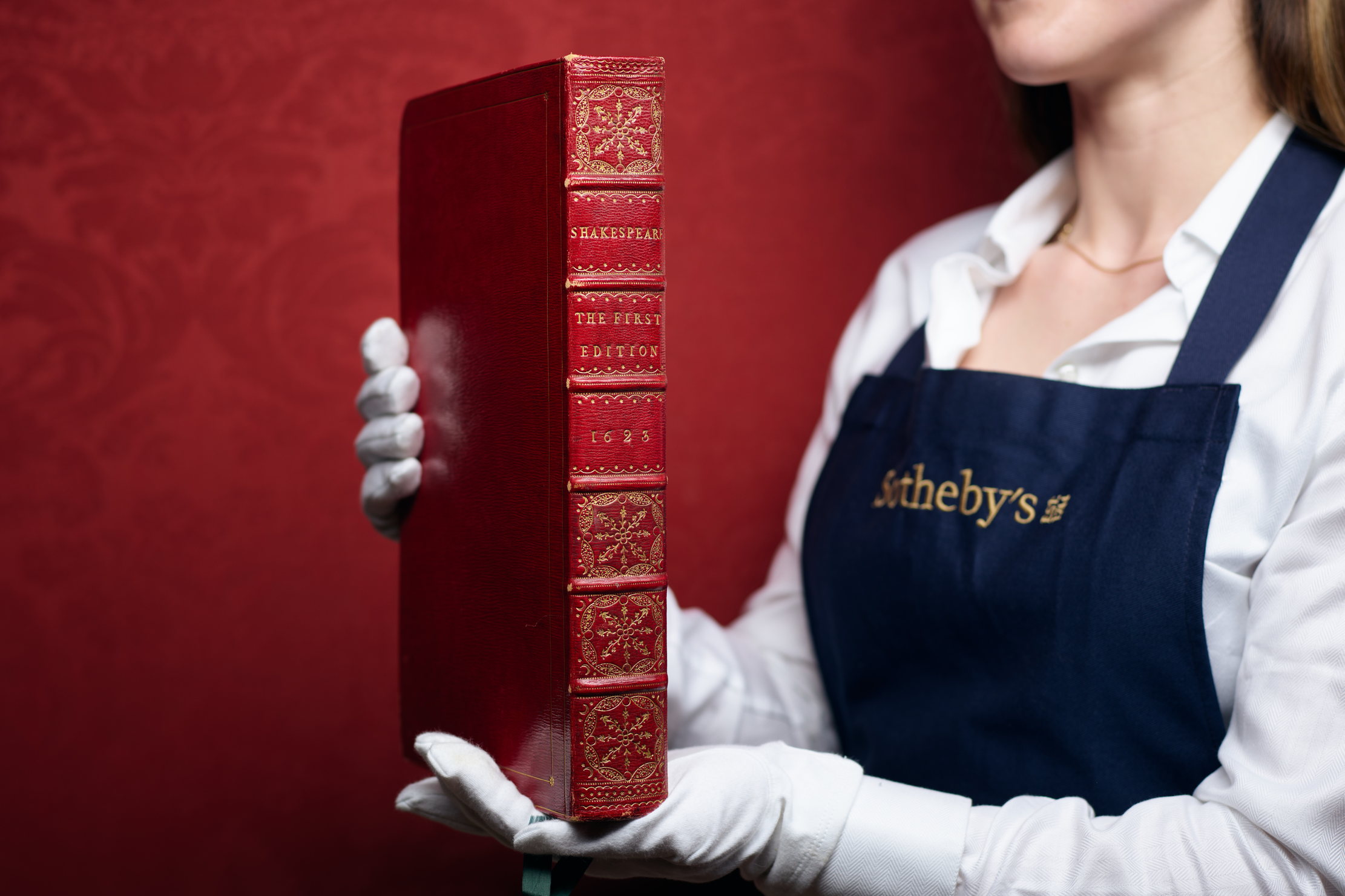

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby's

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby'sFour Folios will be auctioned in London on May 23, with an estimate of £3.5–£4.5 million for 'the most significant publication in the history of English literature'.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Curators, art historians and other creative minds share their pick of J. M. W Turner's best works, on the 250th anniversary of his birth

Curators, art historians and other creative minds share their pick of J. M. W Turner's best works, on the 250th anniversary of his birthCold moonlight, golden sunset and shimmering waters are only three reasons to love Turner. On the 250th anniversary of his birth, curators, art historians and other creative minds reveal which of his paintings they’d hang on their walls and why.

By Carla Passino

-

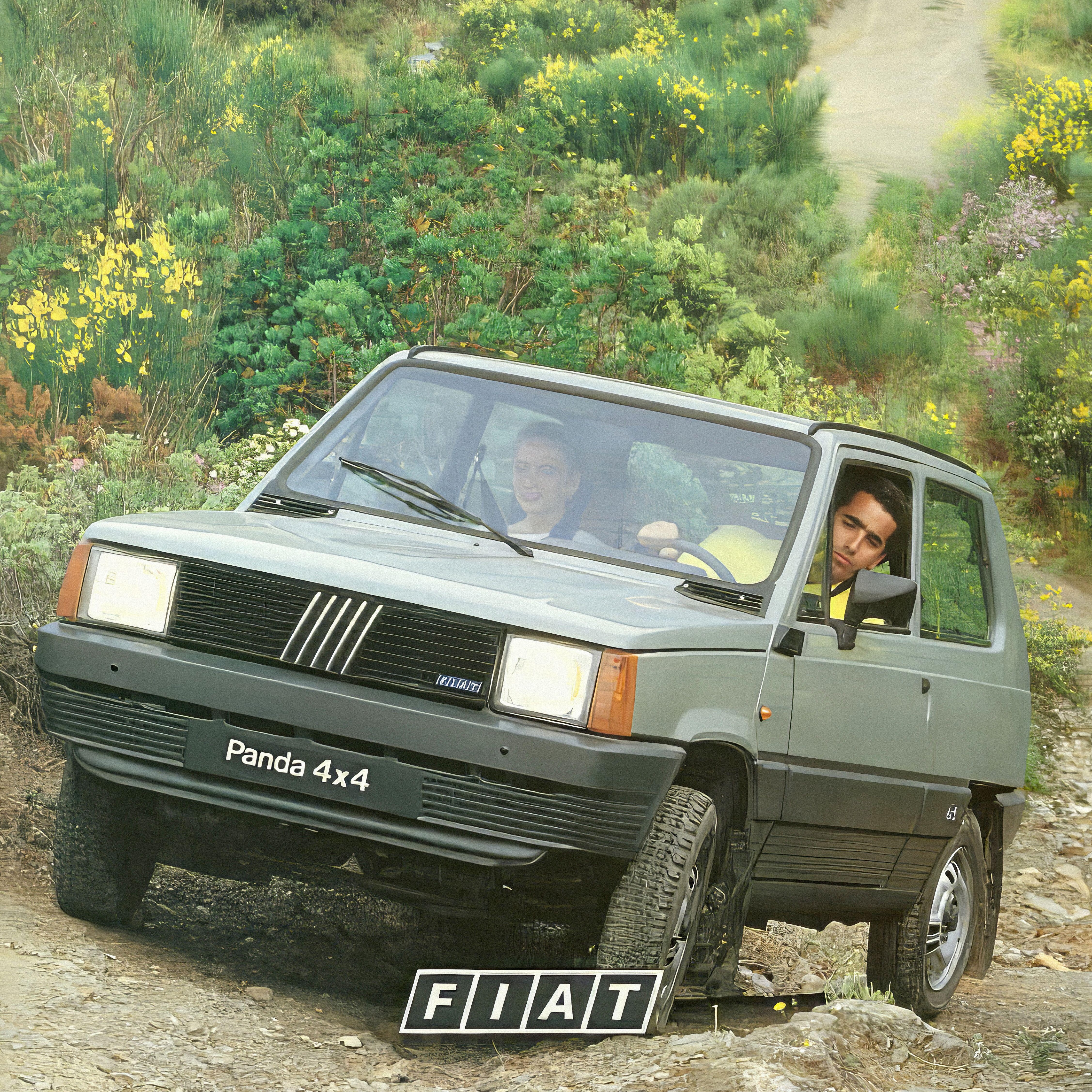

Boxy but foxy: How the humble Fiat Panda became motoring's least-likely design classic

Boxy but foxy: How the humble Fiat Panda became motoring's least-likely design classicGianni Agnelli's Fiat Panda 4x4 Trekking is currently for sale with RM Sotheby's.

By Simon Mills

-

The coveted Hermès Birkin bag is a safer investment than gold — and several rare editions are being auctioned off by Christie’s

The coveted Hermès Birkin bag is a safer investment than gold — and several rare editions are being auctioned off by Christie’sThere are only 200,000 Birkin bags in circulation which has helped push prices of second-hand ones up.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the fun

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the funFrom November, the Ford Focus will be no more. We say goodbye to the ultimate boy racer.

By Matthew MacConnell

-

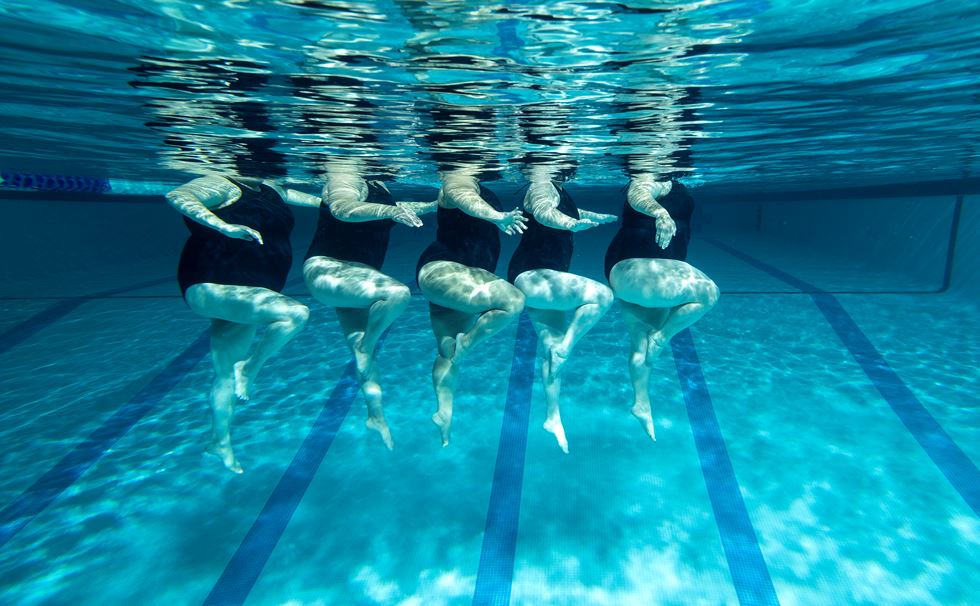

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead Heath

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead HeathEmma Hughes dives into swimming's hidden depths at the Design Museum's exhibit in London.

By Emma Hughes

-

Diamonds are everyone's best friend: The enduring appeal of one of Nature's sparkliest treasures

Diamonds are everyone's best friend: The enduring appeal of one of Nature's sparkliest treasuresEvery diamond has a story to tell and each of us deserves to fall in love with one.

By Jonathan Self

-

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old Masters

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old MastersThe younger generations’ appetite for everything vintage bodes well for the future, says Huon Mallalieu, at a time when an extraordinary Old Masters collection is about to go under the hammer.

By Huon Mallalieu