The tragic tale of Rex Whistler, the brilliant young artist whose time at the Front Line lasted less than 24 hours

Rex Whistler, determined that the Second World War shouldn’t be left to young boys, worked hard to become an officer and lead troops into battle, but the naivety of early courage cost him his life on his very first day of battle, as Allan Mallinson reveals.

Rex Whistler was up a scaffold with his portable radio in the saloon at Mottisfont Abbey in Hampshire when he heard the news. Dipping his brush, he wrote a message on top of the cornice by the bay window, before hurrying to Salisbury to be with his parents on their way to the cathedral: ‘I was painting this Ermine curtain when Britain declared war on the Nazi tyrants. Sunday, September 3rd, R.W.’

Whistler — Reginald John, but always ‘Rex’ — was then 34 and comfortably off. At the Slade School of Fine Art, which he’d entered in 1922, his professor, Henry Tonks, had been in no doubt of his talent: ‘Directly he is launched, he will be an amazing success.’ And he was. In 1925, the Tate Gallery wanted to revamp its gloomy basement refreshment room. Tonks championed his protégé and, over 18 months, Whistler would create a 55ft narrative mural, The Expedition in Pursuit of Rare Meats, depicting a party of eccentric gastronomic adventurers travelling through exotic landscapes searching for unusual delicacies to eat. Tonks declared it ‘the most amusing room in Europe’ when it reopened in November 1927. Although now considered problematic, at the time, the mural, with its ‘frivolously gallant style’, won the artist a series of private commissions and much social cachet.

Whistler — who is the subject of an exhibition at the Salisbury Museum which runs until the end of September 2024 — had a background which was relatively humble. He was born in 1905 in the London suburb of Eltham, where his father was a builder and his mother a clergy daughter. They managed to send both sons to public school — Laurence, the younger, to Stowe; Rex to Haileybury.

Later, at the Slade, Whistler became close friends with Stephen Tennant, youngest son of the 1st Baron Glenconner and Pamela, née Wyndham, one of the three Wyndham sisters of Sargent’s celebrated portrait. Tennant would become prominent among what the popular papers called the Bright Young Things, with whom Whistler, lean, good looking, charming, witty with both word and brush, would soon be numbered.

Tennant was consumptive and, in 1924, when at the Slade, Whistler accompanied him on a curative visit to Switzerland and Italy. Tennant’s mother had taken a house in Sanremo and, in the new year, invited Edith Olivier, a 52-year-old bluestocking spinster and Wiltshire neighbour, to join them. Whistler and Olivier began an intense, platonic and enduring attachment.

In 1936, he began what was perhaps his most dramatic mural, a European fantasy landscape with a background of Snowdonia for the dining room of Plas Newydd, seat of the Marquess of Anglesey on the island. For some time, Whistler had been pursuing one of Anglesey’s daughters, Caroline Paget, eight years his junior. The love — obsession — was not requited and certainly not consummated, but they holidayed abroad together. Physical relief for Whistler came only with a succession of married women, including Siegfried Sassoon’s estranged wife, Hester, and with the Hollywood star Tallulah Bankhead.

Rex Whistler: Life and times

- June 24, 1905 Born in Eltham, London

- 1919 Enters Haileybury College, Hertfordshire

- 1922 Begins at the Royal Academy, London, but leaves after one term and moves on to Slade School of Fine Art

- 1927 Completes The Expedition in Pursuit of Rare Meats at Tate Gallery

- 1940 Commissioned 2nd Lieutenant, Welsh Guards

- June 1944 Crosses to Normandy with 2nd (Armoured Reconnaissance) Battalion Welsh Guards

- July 18, 1944 Killed in action near Caen, during Operation Goodwood

After the Munich agreement in 1938, Whistler tried the Territorials, but they were not looking for officers of his age who lacked military experience. When war did come, in September 1939, he told everyone: ‘This time it can’t be left to the young boys.’ Prospects for a commission were not promising, policy being to select men who showed officer potential during recruit training. The Guards, however, were always something of an army within an army and the Welsh Guards took him, although their colonel doubted that he’d be able to give him any active position, for Whistler was well over the usual age for a platoon commander. Nevertheless, he sent him to the regimental tailors to be measured.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

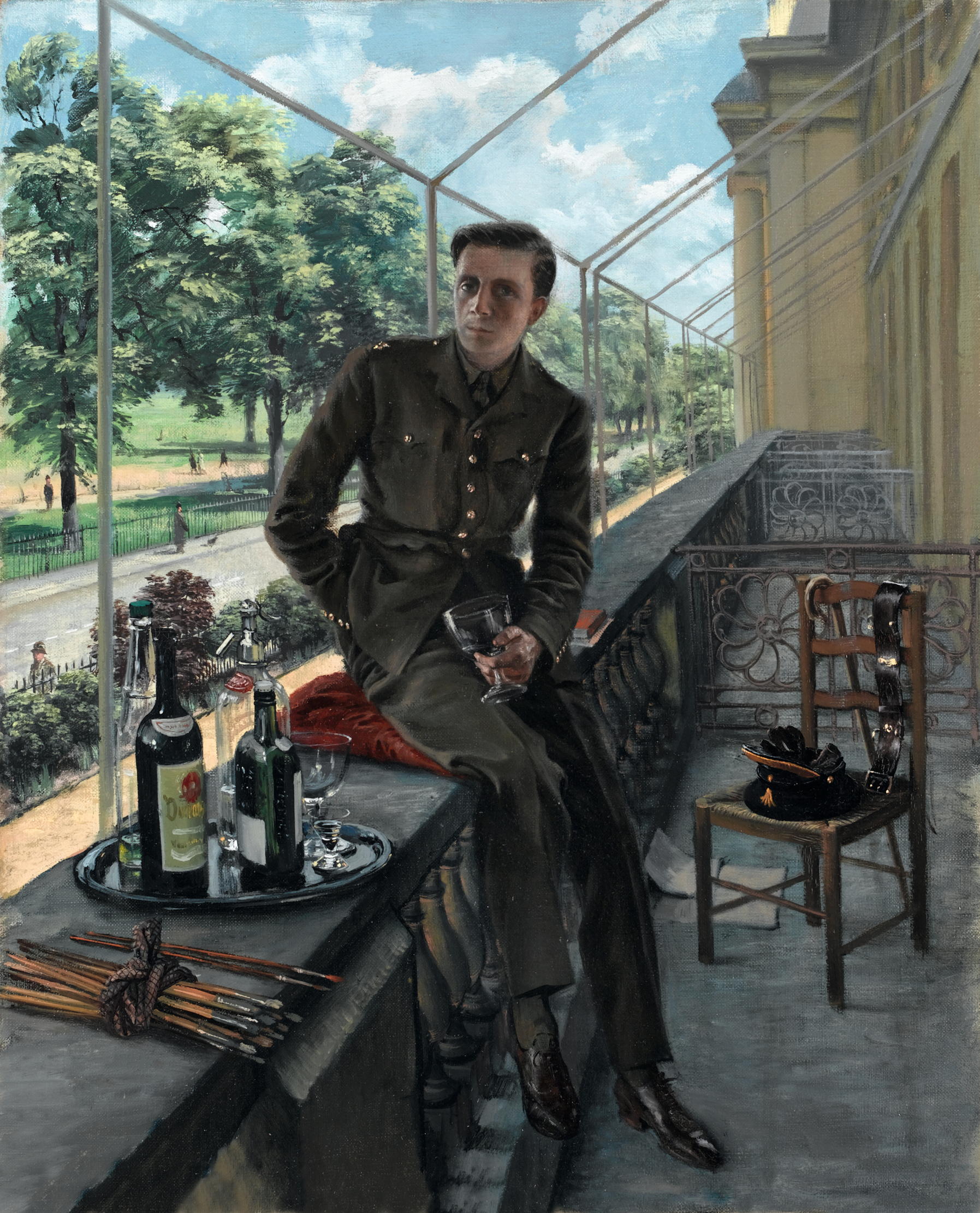

Whistler gave up his studio in Fitzroy Square and moved to the cathedral close in Salisbury, Wiltshire, where, the year before, at Olivier’s suggestion, he had taken a lease on the Walton Canonry for his mother and ailing father. There, he enjoyed ‘the temporary idleness of the Close: Time for reading and for painting odds and ends,’ including a commercial calendar — 12 oil paintings quickly done, but with exquisite draughtsmanship. Not until April was his uniform ready. After collecting it, he returned to the flat off Regent’s Park where Paget’s sister had lent him a room for a studio, put it on and painted a self-portrait. Although marvellously debonair, it has a distinctly ‘Goodbye to All That’ look.

However, it was another two months before he received orders to report to the Welsh Guards’ training battalion in Colchester, Essex. ‘I know I shall make an idiotic soldier’, he wrote to Anglesey. For a time, it seemed so. Within days, he was in trouble, having forgotten his tie when rushing, late, to get on parade. He only survived training, he said, by ‘looking at my watch every quarter of an hour and doing what the others [were] doing’.

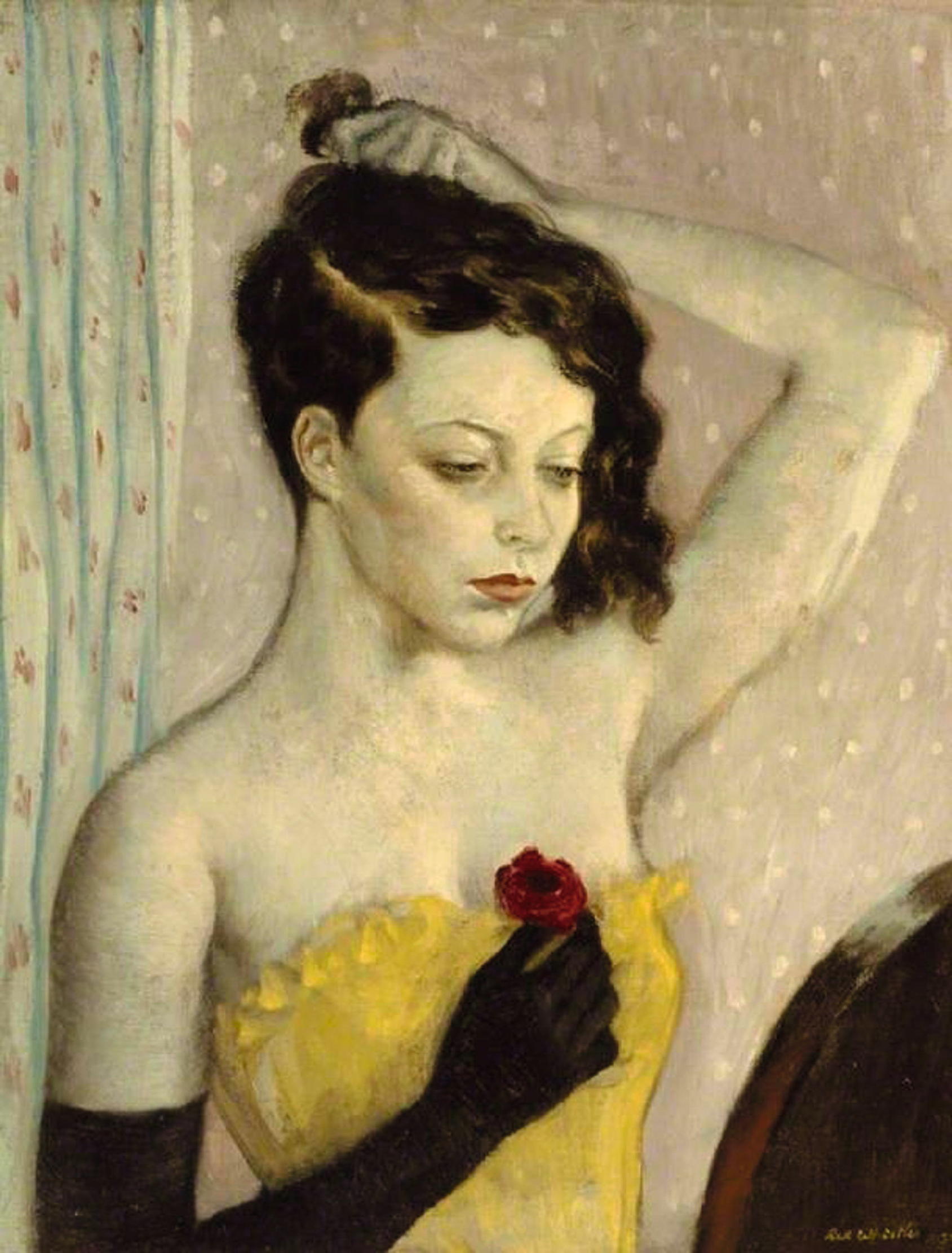

After the battalion moved to the racecourse at Sandown Park in Surrey, when France had fallen and England stood in expectation of invasion, Whistler kept painting, including two memorable portraits — the battalion’s master cook and a fellow officer, ‘Jock’ Lewes, Bren gun on knee — and even paid commissions. Things were shaping up for a long war.

Early in 1941, the War Office decided that the Guards would form an armoured division and 2nd Battalion Welsh Guards, to which Whistler was now posted, was one of the units earmarked for conversion to tanks. In September, the Guards Armoured Division assembled near Salisbury Plain: 2nd Welsh Guards occupied ‘an unfinished camp with no hard standings and only indescribable mud’ at Codford, with a handful of tanks, all obsolete.

Whistler’s father had by then died, his mother had gone to live with relatives and the army had requisitioned the canonry, but the proximity of Olivier and friends (Sassoon only three miles away at Heytesbury) made winter bearable. In February, new tanks began arriving and the divisional commander decided that ‘the all-seeing eye’ that had been the Guards’ divisional sign in the First World War should, with slight modifications, become the same for Guards Armoured, too. Whistler was called on to paint different eyes on a dozen vehicles, which then paraded for the winner to be chosen by a panel of senior officers.

With the threat of invasion now receding came the prospect of liberating occupied Europe. The 2nd Welsh Guards became an armoured reconnaissance regiment, equipped with Cromwell tanks — fast, with good armour and a powerful gun. It was time for Guards Armoured to quit the Plain for more intensive training. On March 1, 1943, St David’s Day, Whistler’s battalion held a farewell service in Salisbury Cathedral: 700 (predominantly) Welsh voices — an incomparable choir.

The division eventually moved to Norfolk and Whistler, much liked and respected by his troop of 14 guardsmen — especially his sergeant, Lewis Sherlock — was invited with several senior officers to Sandringham. At dinner, he sat next to the 17-year-old Princess Elizabeth, writing to his mother afterwards that he found her ‘gentle from shyness but not too shy, and a delicious way of gazing — very serious and solemn — into your eyes while talking, but all breaking up into enchanting laughter if we came to anything funny’.

During these years, there was leave and recreation, but also a growing concern that at his age, Whistler really ought not to be leading a troop. The new divisional commander, Maj-Gen Allan Adair, wanted him for his headquarters. Whistler told his commanding officer: ‘Well, I’m bloody well not going — Sir! I’m going to stay with my troop!’ Adair, a shrewd, much-decorated Grenadier, did not press him.

In late summer, they moved to the Yorkshire Wolds, where they finally had space for realistic battle practices. ‘Tragic as the sight of ruined crops and hedgerows must have been to the local landowners and farmers, the value of the lessons provided for us was immeasurable,’ records the divisional history. They stayed the winter, Whistler also working on set designs for a West End performance of An Ideal Husband, Sadler’s Wells’s ballet Le Spectre de la Rose and a film with James Mason, A Place of One’s Own — as well as the decorations and invitations for the battalion’s Christmas party for 300 local children.

In April 1944, the division moved again — to Sussex, not for the D-Day landings, but ready for the breakout from Normandy. On June 19, days before Whistler’s 39th birthday, they crossed to France, but still had to wait a month before seeing action. Caen stood in the way and Rommel had seven Panzer divisions ready. Gen Montgomery decided to attack on a narrow front east of the city, with three armoured divisions advancing like a wedge, Guards Armoured left-rear: ‘Operation Goodwood.’ On July 16, 2nd Welsh Guards learned they would be protecting the flanks. Whistler, as the battalion burial officer, would carry 20 white crosses in the metal box the blacksmith in Codford had made for his paints and brushes, fixed to his tank’s turret. His troop thought it ominous.

Near the village of Giberville, Whistler’s troop had to cross a railway cutting into which telegraph wires had fallen. He ordered his other two tanks across first, but his own failed to get up the far side. Dismounting, he saw the offside sprocket was fouled by wire, so told the crew to dismount to help free it — a mistake, leaving the radio unmanned. Minutes later, machine-gun fire struck the tank. More bursts followed. Trying to remount to radio his sergeant, Sherlock, would have been suicidal, so Whistler decided to sprint the 50 yards to his tank to tell him to clear the village. He succeeded, but then made a second mistake, sprinting back rather than crouching on the blind side of Sherlock’s tank. As he jumped down, a mortar bomb fell close, blowing him 10ft into the air. Sherlock knew at once that Whistler was dead.

That night, Sherlock asked leave to take a scout car to bring his troop leader back for burial. When he reached the spot, he found a shallow grave with a crude cross marked ‘an unknown officer’. All he could do was substitute Whistler’s name in red wax pencil.

Whistler was later reburied in the war-graves cemetery at Banneville-la-Campagne. His death had been the mistake of inexperience, the naivety of first courage. John Gielgud wrote a eulogy in The Times: ‘O that it should have come to this.’ Country Life published a three-page, illustrated tribute by Edith on September 1. Some thought it over the top (she compared him to the Elizabethan Sir Philip Sidney), but it ended with the incontestable esteem of his regiment: ‘He made himself most beloved by us all, officers and men.’

Lewes, the officer he had painted at Sandown, had been killed in North Africa with the Special Air Service in 1941, but, in 2nd Battalion Welsh Guards, Whistler had been first to fall.

‘Rex Whistler: The Artist and His Patrons’ is at the Salisbury Museum, Wiltshire, until September 29, 2024

Image credits: Angelo Hornak/Rex Whistler Archive/The Salisbury Museum; National Army Museum /Bridgeman Images Dan Brown/Rex Whistler Archive/The Salisbury Museum

A £13 million Wiltshire mansion where Nancy Mitford and Siegfried Sassoon once partied with 'the brightest of the Bright Young Things'

After Wilford Manor's glory days in the 1920s it became a near-wreck with a tree was growing out of one of

'One of the wonders of Oxford': A look at the extraordinary Campion Hall

In the second of two articles, Clive Aslet looks at the furnishing of Campion Hall, particularly the treatment of the

In Focus: Eric Ravilious, the war artist with a fascination with the quotidian whose work was 'sharp in detail, clean in colour' and 'quietly revolutionary'

Known as ‘the boy’ and only 39 when he died on active service in the Second World War, Eric Ravilious