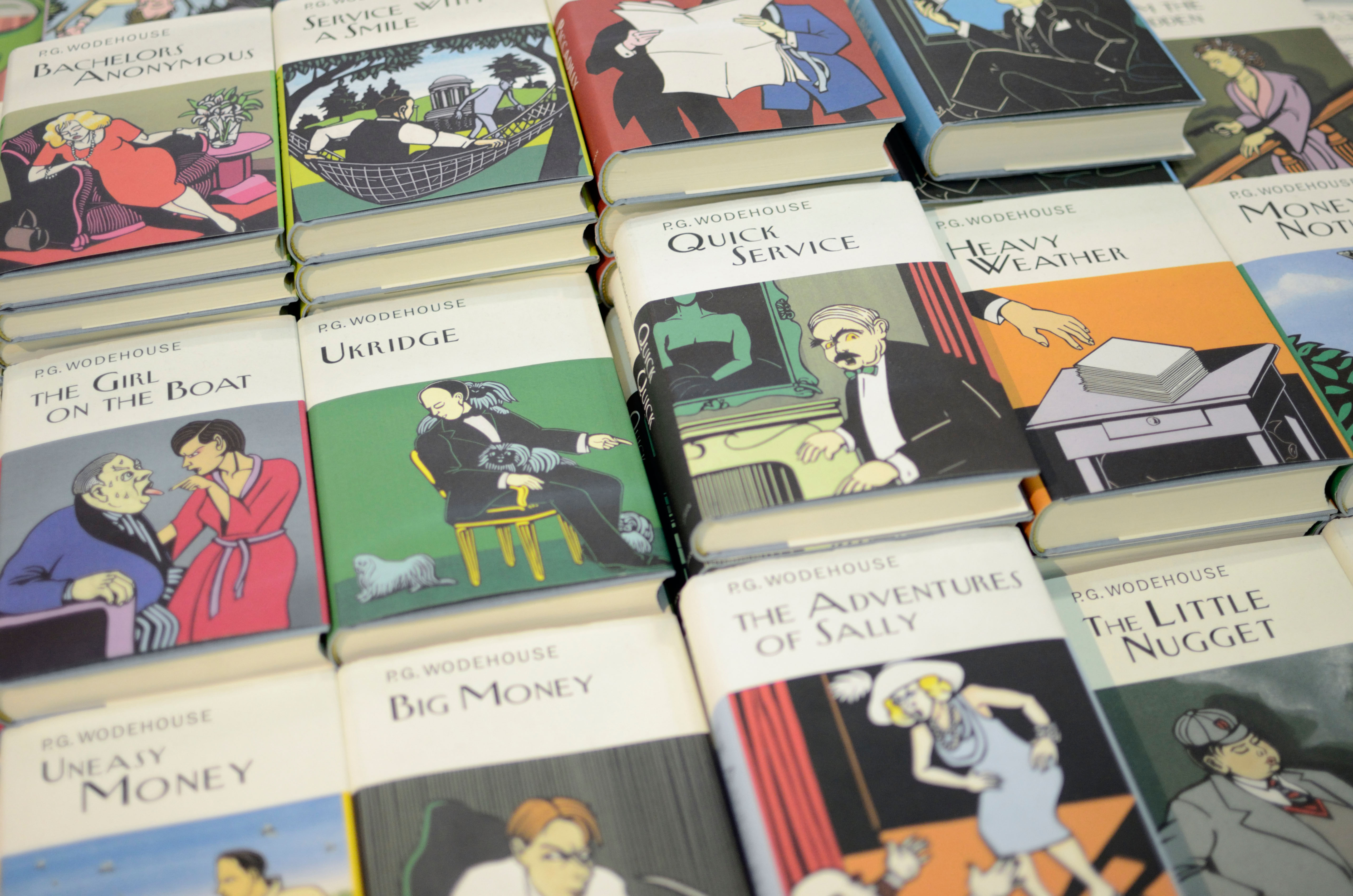

The life and times of P. G. Wodehouse, 50 years on from his death

Bertie Wooster, Jeeves, Lord Emsworth and the Blandings Castle set: P. G. Wodehouse’s creations made him one of the most widely read humorists of the 20th century, but he was denounced as a traitor and a Nazi.

On Valentine’s Day 50 years ago, P. G. Wodehouse died, aged 93. The writer of sentences such as ‘I could see that, if not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled’, he has long been admired by other writers.

To Bernard Levin, he was ‘one of the finest and purest writers of English prose’. Rudyard Kipling considered Lord Emsworth and the Girl Friend ‘one of the most perfect short stories’. Evelyn Waugh said ‘one has to regard a man as a Master who can produce on average three uniquely brilliant and entirely original similes to every page’.

The Oxford English Dictionary cites Wodehouse multiple times as the inventor or first recorded user of a phrase or for particular use of a word in a specific sense or with a certain nuance. How many of these were Wodehouse inventions, rather than him picking up on something and being the first known to use it, isn’t clear, but he is suggested as the inventor of such phrases as ‘down to earth’ and ‘pain in the neck’.

‘What Wodehouse writes is pure word music,’ believed Douglas Adams. ‘It matters not one whit that he writes endless variations on a theme of pig kidnappings, lofty butlers, and ludicrous impostures. He is the greatest musician of the English language, and exploring variations of familiar material is what musicians do all day.’

Wodehouse had originally made his name in musical theatre and was involved with some 50 dramatic works, mostly in collaboration. He took a while to find his feet as a novelist, experimenting with different genres before establishing himself as a farceur.

Stephen Mangan as Bertie Wooster and Matthew Macfadyen as Jeeves in a Wodehouse adaptation London's Duke of York Theatre in 2013

Later in life, he wrote to a friend: ‘There are two ways of writing novels. One is mine, making the thing a sort of musical comedy without music, and ignoring real life altogether; the other is going right deep down into life and not caring a damn. In writing a novel, I always imagine I am writing for a cast of actors.’

His parents lived in Hong Kong, where his father worked, but Wodehouse — known as Plum — was born in Guildford, Surrey, at the home of an aunt; his mother was visiting and he arrived early. After a brief spell in Hong Kong, he was returned to England from the age of two, when he was sent to a governess, together with his two older brothers, and hardly saw his parents until he was 15, when his father retired to England.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

By then, the boy was at Dulwich College, which was to remain a love of his life. Even when he was a successful author living in France, he travelled over to report school cricket matches for its magazine. When the XI went through the 1938 season unbeaten, he paid for them to have dinner in London’s West End and watch a show at the Palladium.

Wodehouse was a school prefect, the editor of the school magazine and a fine all-round sportsman. He boxed, was a forward in the first XV and had two seasons in the cricket XI as a fast bowler. He played alongside Neville Knox, who was to play for England and would be described by Sir Jack Hobbs as ‘the best bowler I ever saw’. Wodehouse claimed one of his proudest achievements was that he used to get on to bowl before Knox, ‘although he was a child of about 10 then’. Knox was, in fact, three years younger than Wodehouse. The author continued to play cricket as an adult, was a member of Surrey County Cricket Club and named Bertie Wooster’s valet after Percy Jeeves, a Warwickshire player whose bowling action he admired.

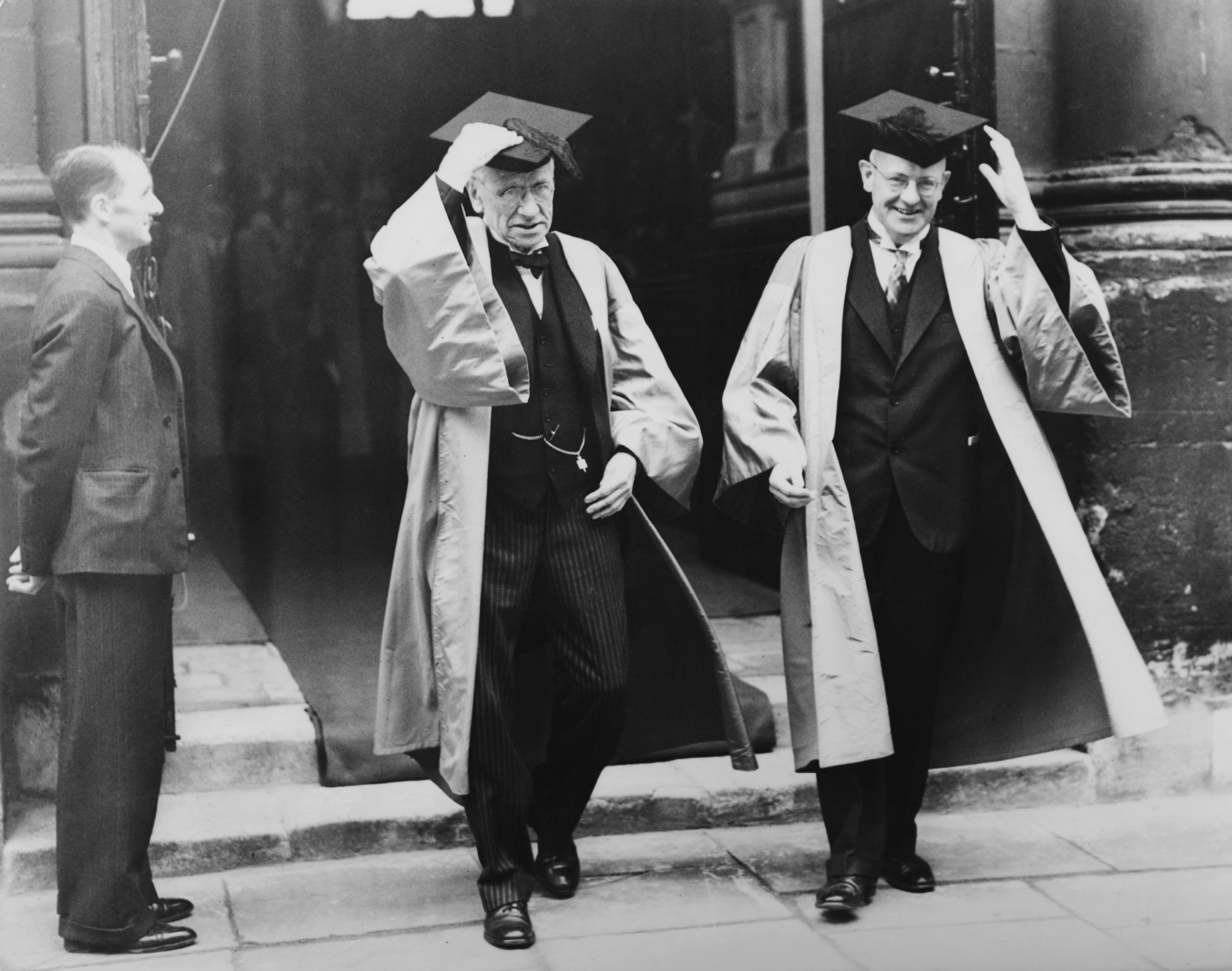

Wodehouse (right) with literary critic Herbert John Clifford Grierson after they both received the honorary degree of Doctor of Letters from Oxford University in 1939

Schoolfriend Bill Townend, who also became an author, remembered Wodehouse’s attitude to prep: ‘He worked, if he worked at all, supremely fast, writing Latin and Greek verses as rapidly as he wrote English. Certainly the two hours were not filled entirely with work: we talked incessantly about books and writing. Plum’s talk was exhilarating. I had never known such talk. Even at the age of 17 he could discuss lucidly writers of whom I had never heard… And from the first time I met him he had decided to write.’

Wodehouse had been destined for university, but his father decided he couldn’t afford to send another son, so he was put to work in a bank instead. He wrote in his spare time and, as soon as he was confident of making a living as a freelance author and journalist, he left banking. Keen to get his fiction accepted by the better-paying American magazines, he turned to a subject that the local authors weren’t writing about — the English aristocracy. Wodehouse had found his niche and light comedies featuring the aristocracy became his staple.

Once he had found his metier, writing held few perils for him, but he was always anxious about finding plots. Outside of the ‘Jeeves & Wooster’ and ‘Blandings Castle’ series, he would often resort to adapting or buying other’s plots, turning theatrical works into novels and vice versa. The idea for Uncle Fred Flits By, rightly declared his best short story in a survey of Wodehouse societies worldwide, was developed from a suggestion by his friend Townend.

Once Wodehouse had an idea for a plot, he wrote a detailed structure — often as much as one-third of the length of the finished work. He averred that he always thought that in writing the novel he was wasting valuable time, as the difficult part was in drawing up the plot.

The Wodehouses — he married Ethel Wayman in 1914 and adopted her nine-year-old daughter, Leonora — lived in America and England, so Plum faced double taxation on all his earnings, with both countries wanting to tax him as a resident.

The family, therefore, moved to Le Touquet in 1934. When the Germans captured France, the writer was sent to an internment camp, where he gave some well-received talks to his fellow internees.

On his release after nearly a year, on grounds of age, he used these as a basis for five talks to neutral America. Light in tone, they were designed to show that morale remained high among the internees, as well as poking mild fun at the Germans. The British Government was furious that he had broadcast from Germany, regardless of what he said (most Britons had no knowledge of what he had said), and orchestrated a vituperative, dishonest campaign against him. Denounced as a traitor and a Nazi, his works were banned by libraries and the BBC.

The Wodehouses eventually returned to France and, when that country was liberated, Plum was arrested by the French. He was interviewed by Maj Edward Cussen, a barrister who worked for MI5, who reported that Wodehouse’s broadcasts did ‘not contain material of a pro-German character’ and that he ‘has not been guilty of treasonable conduct’. Yet the Government never officially exonerated him: the Cussen Report was not released in Wodehouse’s lifetime and it was only in the 1960s that he was assured, albeit still unofficially, that he would not be arrested if he returned to England.

He had gone into exile in America in 1947, settling in Remsenburg, a village outside New York, and taking American nationality in 1955. He still, however, set most of his work in England and wrote with English spellings.

Wodehouse drinking tea with his wife Ethel on the day he was informed about his KBE

In the 1975 New Year’s Honours, the 93-year-old author was given a knighthood, a public sign that the Government had finally ended its quarrel with him. He was too frail to return to England for the ceremony, but the Queen Mother, a self-confessed ‘devoted admirer of his work’, was eager to travel to present him with his gong. Yet her schedule could not be re-arranged and, instead, it was decided that a ceremony would be held in the British Consulate in New York, with the British ambassador doing the honours.

Before then, Wodehouse went into hospital suffering from pemphigus, a skin disorder, taking with him the manuscript of the novel he was working on. By this stage, he had already had nearly 100 books published, as well as many magazine short stories that had never made it into book form.

On 14th February, 1975, Plum got out of bed to walk across the room and died of a heart attack. A fortnight later, the acting Consul General drove to Remsenburg and presented Wodehouse’s insignia and warrant to Lady Wodehouse.

Roderick Easdale is the author of ‘The Novel Life of P. G. Wodehouse’ (Acorn Books).

Roderick Easdale is a regular contributor to Country Life on topics including sport and property. He also compiles the magazine's crossword, every other week.