The English country house as seen in the art of Turner, Constable and their modern-day successors

Ever since a craze for house portraits reached Britain in the 17th century, great artists such as J. M. W. Turner have been producing sweeping vistas of stately Edens, observes Michael Prodger.

J. M. W. TURNER was the son of a Covent Garden barber and wig maker, but, for all his humble beginnings, he rapidly became familiar with some of England’s grandest country houses. His talent was such that assorted grandees treated him as a friend of similar social status, rather than merely a commissioned painter, and invited him to stay with them as an honoured guest — sometimes for months at a time — at an assortment of stately residences.

Chalfont House in Buckinghamshire, Hampton Court in Herefordshire, Towneley Hall in Lancashire, Fonthill Abbey in Wiltshire, Radley Hall in Oxfordshire — Turner criss-crossed the country painting houses and castles that sit languorously or dramatically in the landscape. Sometimes, his depictions were workaday records of windows, pediments and columns. Yet, at others, the houses become the stuff of dreams, visions of ideal slices of England, where harmonious architecture takes its place in the embrace of Nature. He became a regular at Petworth House in West Sussex, seat of the Earl of Egremont; at Farnley Hall in North Yorkshire, the home of Walter Fawkes, landowner and MP; at Harewood House, South Yorkshire, the unfeasibly majestic domain of the Earl of Harewood; and at Tabley, in Cheshire, the home of Sir John Leicester. Numerous watercolours of these imposing houses serve as a record of the rarefied world the low-born painter inhabited.

Usually, Turner knew how to behave himself. At Petworth, for example, the artist and the Earl once fell into an argument about whether carrots float, which was amicably settled when the nobleman rang the bell and demanded a bucket of water and some of the vegetables to be brought. Turner was proved right, the Earl conceded and all was well. Things were frostier at Tabley when, on a visit to paint prospects of the house and enjoy its amenities, Turner was asked by his host for his opinion on some of his own amateur paintings, which he duly gave. Sir John was startled, a short time later, to receive a bill from the artist for ‘painting lessons’. He paid up, but, having been one of Turner’s most faithful patrons, he bought only one more picture from him.

The country-house painting tradition that Turner and his patrons tapped into was a relatively modern one. Although views of English country houses date back to the 16th century, especially in decorated, but utilitarian estate maps, it was not until the later 17th century that portraits of houses became an established genre. A taste for such scenes was already highly developed across the North Sea. Even the great Rubens tried his hand, with one of his most celebrated works showing his own house and land, A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning, dating from about 1636.

Many Royalists fled to the Netherlands during the Civil War and, under the Restoration, returned with an urge to have their own trophy homes depicted. The fad accelerated in 1689 with the accession to the throne of William of Orange and his wife, Mary, when the Low Countries influenced every aspect of English culture. When artists such as the Flemings Jan Siberechts (1627–c.1700) and Peter Tillemans (1684–1734) arrived on these shores, they found a ready market for their work.

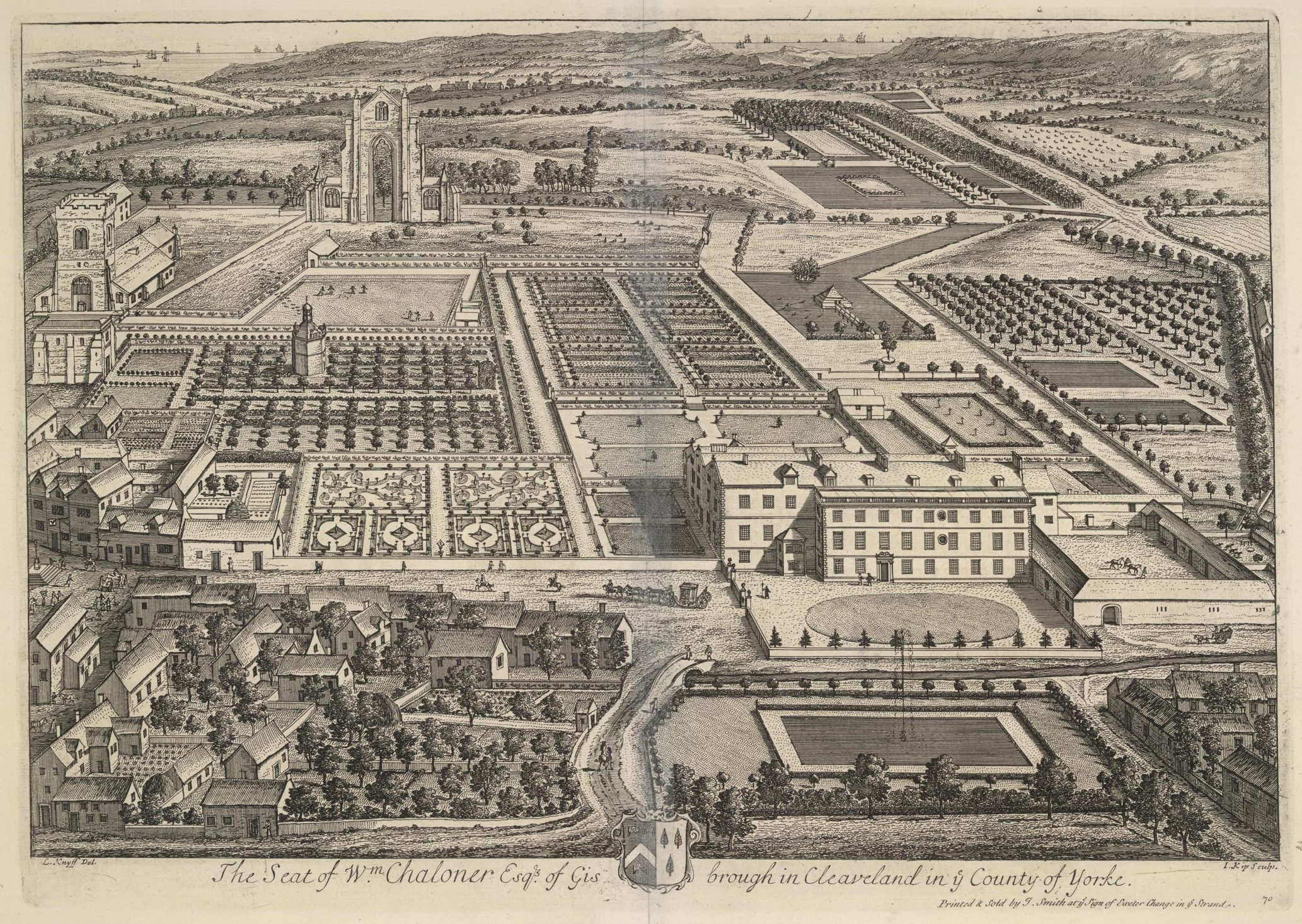

These painters gave their patrons accurate depictions of country seats — Longleat House, Wiltshire; Chatsworth, Derbyshire; Wollaton Hall and Newstead Abbey in Nottinghamshire, to name a few — to hang in their London homes and remind themselves of the joys of the pastoral, as well as impress visitors. Both artists usually painted from a high viewpoint to show the houses to best effect and, with another of their countrymen, Pieter Andreas Rijsbrack, sometimes went a stage further.

As even drawing from a hilltop couldn’t give a full idea of some landowners’ domains, they adopted what was known as the ‘Sienese map perspective’ and showed the houses, gardens and parklands as if seen from a balloon looking down. Such pictures represent an extraordinary imaginative leap, as well as a bravura technique to make such unseeable vistas coherent. What they offered was a whole world in miniature: a house at the centre with allées of trees radiating outwards; formal gardens; parkland and agricultural land (although rarely the estate workers’ cottages); and the woods, hills and waterways of the owner’s estate. If Louis XIV could say of France ‘L’Etat, c’est moi’, then the owners of these Edens could at least claim: ‘Le domaine, c’est moi.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

This taste for a literal overview of houses and land was spread further by printmakers. Not everyone could own a country home, but richly illustrated and expensive volumes such as Britannia Illustrata: Or Views of Several of the Queen’s Palaces, also of the Principal seats of the Nobility and Gentry of Great Britain, 1707–09, by Johannes Kip and Leonard Knyff, allowed aspiring Britons to dream of what they might have, exactly as the mass of house and home magazines and television programmes do today.

These print series also recorded the emergence of new architectural tastes. The publications of architect-scholars, such as Colen Campbell and William Chambers, as well as spreading their own renown, showed the emergence of British Palladianism, too, a style that is now synonymous with Georgian architecture and the English country house. Campbell, who worked at both Houghton Hall in Norfolk and Stourhead in Wiltshire, knew what was what. His Vitruvius Britannicus, or the British Architect, published in three volumes from 1715 to 1725, was not only a record of our grandest buildings, but a work of national pride. The images of sweeping, columned façades were meant to show how the work of great British architects was also a repudiation of the excesses of Continental Baroque. These were buildings that reflected the orderly and rational temperament of God’s own country.

In the later Georgian era, the taste was for increasingly naturalistic pictures of houses in their landscapes. Although Constable was happy to oblige Maj-Gen Francis Slater Rebow and paint Wivenhoe Park in Essex for him in 1816, not every painter was keen. Gainsborough may have been a peerless portraitist of the human face and figure, but, much as he loved painting landscapes, he couldn’t bring himself to portray the nooks and crannies of a building. When, in 1764, Lord Hardwicke approached him to paint his country home, Wimpole Hall in Cambridgeshire, the artist gracefully deflected the commission towards an admired colleague. ‘With respect to real Views from Nature in this Country,’ he said, ‘Paul Sandby is the only Man of Genius… who has employ’d his Pencil that way.’

Sandby had learned his trade as a map maker in Scotland in the years after the Jacobite rebellion and had an eye for detail and topography that he turned to good account in both his watercolours and his prints; he would later serve for more than 30 years as chief drawing master at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. Sandby understood better than anyone the way that some houses and their settings can form a new and enhanced whole and his pictures amount to a record of Georgian Britain’s most notable buildings.

Country-house painting is not a thing of the past. It certainly thrived in the 20th century. Following the turmoil of the First World War, Algernon Newton responded to the need for a return to order by painting houses such as Godmersham Park in Kent or Gainsborough’s rejected Wimpole Hall in images of utter stillness, timeless and reassuring. John Piper toned down his early avant-gardism to depict Blenheim in Oxfordshire and the Sitwells’ Derbyshire Renishaw under moody skies. Hugh Casson, architect, artist and president of the Royal Academy, filled his sketchbooks with watercolours and drawings of grand homes.

Artists continue this tradition today. James Hart Dyke, born in 1966, has not only painted Mount Everest and been artist-in-residence for the British Secret Intelligence Service, he has made images in a romantically inflected style of Highgrove in Gloucestershire (he has also accompanied The King on royal tours) and Stonor Park in Oxfordshire.

Phoebe Dickinson has forged a fruitful career as a portraitist of both people and houses. Her pleasing bricks and mortar pictures of such places as Houghton and Belvoir Castle in Leicestershire are currently being shown in ‘Great Houses and Gardens of England’.

Benjamin Disraeli, who, as the owner of grand Hughenden Manor in Buckinghamshire, had privileged knowledge, spoke of that ‘soul-subduing sentiment, harshly called flirtation, which is the spell of a country house’. Sentiments and flirtation, let alone spells, are hard things to capture, but some painters have managed to do exactly that.

‘Great Houses and Gardens of England’ is at the Simon Dickinson Gallery, London SW1, until November 23 (020–7493 0340; www.simondickinson.com). Visit www.jameshartdyke.com to find out more about James Hart Dyke.

-

Minette Batters: 'It would be wrong to turn my back on the farming sector in its hour of need'

Minette Batters: 'It would be wrong to turn my back on the farming sector in its hour of need'Minette Batters explains why she's taken a job at Defra, and bemoans the closure of the Sustainable Farming Incentive.

By Minette Batters Published

-

'This wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness': One writer's odyssey to the end of the world

'This wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness': One writer's odyssey to the end of the worldWhere else on Earth can you find more than 752,000 acres of splendid isolation? Words and pictures by Luke Abrahams.

By Luke Abrahams Published