The English climate destroyed almost all our medieval church paintings — but not these ones

Winged creatures, robed figures and celestial bodies are under threat in a rural church. Jo Caird speaks to the conservators working to save northern Europe’s most complete Romanesque wall paintings.

As you walk into the dimly lit chancel of St Mary’s in Kempley, Gloucestershire, it’s hard to know where to look first. Behind and around the altar of this pretty church, elaborate decoration covers almost every surface, with winged creatures, robed figures and celestial bodies all vying for your attention. Or, rather, for the attention of the medieval churchgoers for whom this extraordinarily complete Apocalypse scene was painted some 900 years ago.

These frescos, the Christ figure at their centre intended to inspire parishioners to live in accordance with the Lord’s will, have lasted down the ages against the odds. Although works such as this were once found on the walls of churches up and down the country, the rigours of the Reformation, as well as the damp English climate, did away with most of them — but not St Mary’s.

‘For a scheme that intact to have survived and not to be altered, it’s really quite striking,’ says Michael Carter, senior properties historian at English Heritage, which is responsible for the church. ‘We have the most complete cycle of Romanesque wall paintings anywhere in northern Europe.’

English Heritage is trying to keep it that way, but it’s not a straightforward task. At some point during the Reformation, when the rich religious iconography of Roman Catholicism became anathema, the paintings at St Mary’s disappeared under a layer of whitewash. ‘It was a cheap way of covering them up and was what often happened,’ explains Mr Carter. ‘We don’t know what the circumstances were. Was it, “Let’s get rid of it this papalistic nonsense?” Or was it done with a very heavy heart: “One day we’ll be able to remove this and bring this church back to its splendour?” Whatever the reason, it preserves them for later generations.’

However, it does so by placing them in a parlous state. To start with, the whitewash itself may have weakened the underlying 12th-century paint, but that’s nothing compared with what happened next.

In the 1870s, the then vicar of St Mary’s chanced upon the frescos and set about uncovering them — with a palette knife. ‘You can imagine it was a pretty traumatic intervention,’ notes Stephen Rickerby, a specialist wall-painting conservator working with EH to safeguard this precious piece of history for the future. ‘Goodness knows what might have been lost in that process.’

The vicar then applied a supposedly protective coating over the newly uncovered works. ‘That was done with the very best of intentions,’ says Rachel Turnbull, English Heritage’s senior collections conservator, ‘but it hasn’t been ideal for the paintings’ survival.’ ‘In time,’ adds Mr Rickerby, ‘the so-called “preservative” materials went wrong. They darkened and started flaking and causing problems.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It’s Mr Rickerby’s job and that of his colleague Lisa Shekede to assess the extent of those problems. Visual examination of the wall paintings and a comparison with historic photographs enables the conservators to get a sense of the rate at which they are deteriorating, with other hi-tech tools offering further insights. An infrared camera lets the conservators look inside voids in the plaster and portable microscopy gives an up-close view of the damaging 19th-century coating, hopefully providing clues as to what it’s made of. ‘Once we know what it is, we can work out what we can do about it,’ says Ms Turnbull.

Meanwhile, UV light has revealed the extent of that coating: Ms Shekede and Mr Rickerby have found that there are traces of it on almost all the paintings. They aren’t visible to the naked eye, but the other damage certainly is, with details missing from many areas of the works, as well as huge swathes of bare wall where fresh plaster has been applied over the centuries since the cycle was painted.

Standing in the cool of the chancel, surrounded by so much beauty, the paintings’ fragility is palpable. It’s awful to think that, having survived this long, they are still at risk today. The damage also makes it challenging for art historians to interpret their meaning. ‘It’s the case for a lot of medieval paintings,’ reveals Mr Rickerby. ‘You’re trying to piece together the remaining evidence and work out what the iconography was.’

Investigations are still ongoing and only when they are complete will a decision be taken on the best way to safeguard these works for the future. That might mean following in the footsteps of past conservators and attempting to remove the Victorian coating, but such a course is by no means certain, believes Ms Shekede. ‘It’s knee jerk to think that if there’s something there that is non-original, we must remove it. Intervention isn’t always the answer.’

The entire team, however, is aware of the need to respond quickly at moments of particular risk. Ms Shekede and Mr Rickerby have made emergency repairs to the wall paintings during the investigation process, for example, using traditional lime plaster and grout to stabilise some areas of crumbling plaster.

English Heritage hopes to have answers to some of their questions about the paintings later this year, but it’s not a process you can rush, stresses Ms Turnbull. ‘You need to take it a step at a time, because we don’t want to be guilty of doing something that somebody else comes along in the future and says: “It was very well intentioned, but what they did was wrong.” We want to make sure that what we do is for the good of the place.’

Visit www.english-heritage.org.uk to find out more.

-

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'The Paper Mill estate is a picture-postcard in the Garden of England.

By Penny Churchill

-

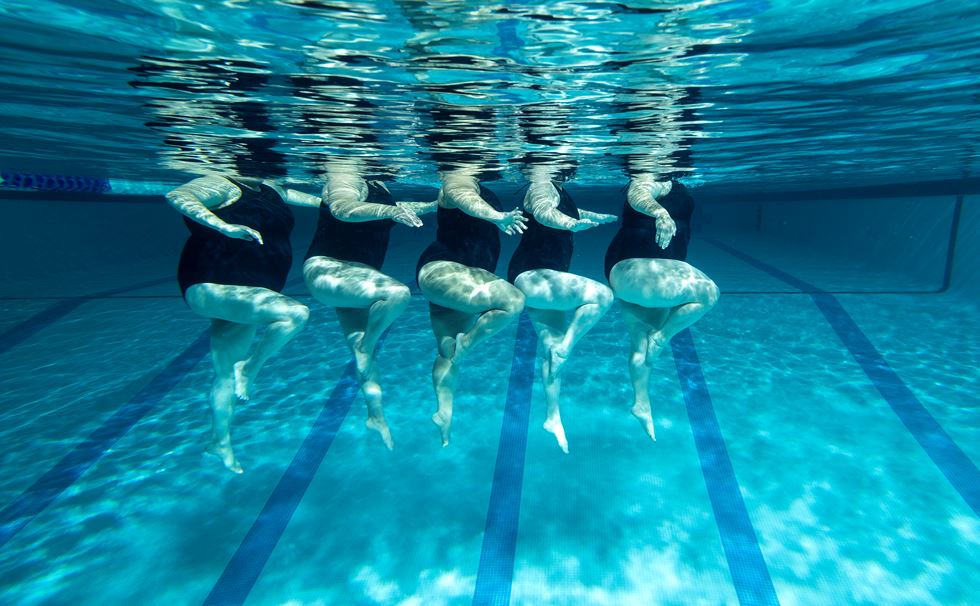

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead Heath

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead HeathEmma Hughes dives into swimming's hidden depths at the Design Museum's exhibit in London.

By Emma Hughes