The art of the storm, from Turner and Rembrandt to Rousseau and Hokusai

Extreme weather has long loomed large in the artist’s imagination. Michael Prodger celebrates the poetic beauty of Nature’s all-consuming fury.

In late 1631, the 25-year-old Rembrandt van Rijn decided to try his luck in Amsterdam. He was, by then, a well-known painter in his native Leiden and had been talent spotted by connoisseurs who suggested he leave his large, but provincial town and aim instead for the upper echelons of Dutch society. Rembrandt made this journey into his future by boat and, in midwinter, it wasn’t plain sailing.

After his arrival in the capital, the young artist painted his only seascape, a large picture depicting Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee. It is a painting of a great drama: Christ is shown in the stern of a Dutch fishing boat among his panicking and praying disciples as a foaming wave lifts the vessel skywards and floods over the gunwales.

As sailors frantically try to lower the sails, one of the Disciples vomits over the side. A break in the clouds sends a spotlight raking over this elemental struggle.

One figure, however, looks out of the painting and directly at the viewer. We know his features well from the innumerable self-portraits that were to follow: it is Rembrandt himself.

Some scholars have suggested that the picture is an interpretation of the painter’s recent voyage from Leiden to Amsterdam when, caught in a gale, the storm-tossed young man wondered if he would ever make it safely to shore. When the green had faded from his gills and it came to depicting the scene, he could call on a long tradition of Dutch maritime art, but Rembrandt was always a close observer of natural phenomena and here the turmoil of roiling sea and scudding clouds is painted with feeling and turned his terror into art. By way of a footnote, the painting has had a stormy history, too. In 1990, thieves broke into the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, US, and stole the painting, as well as several others: it has never been recovered.

If Rembrandt was an inadvertent painter-witness to Nature’s fury, some other artists delighted in storms and studied them with a meteorologist’s eye for detail. Here, after all, were ready-made subjects, replete with excitement and danger, and how better to transmit that ferment to canvas than to live it.

Some two centuries after the seasick Rembrandt staggered ashore, J. M. W. Turner voluntarily put himself through a similar ordeal. Determined to witness a snowstorm at sea from the inside, he set sail at night on a steamship from Harwich and, he claimed, had the sailors ‘lash me to the mast to observe it; I was lashed for four hours, and I did not expect to escape, but I felt bound to record it if I did’. The painting that resulted, Snow Storm: Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth (1842), shows a boat literally in the eye of the storm, caught in the middle of a spiral of wind and water. Land has disappeared, the horizon pitches, air and sea have become one and both vessel and sailors are caught in the vortex as if in a washing machine. Not that every critic, however, was convinced by the visceral portrayal: it was nothing more than ‘soapsuds and whitewash’, carped one.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Did the incident really happen? Four hours in a snowstorm without cover or ill effect seems a stretch and there is no record of the ship Turner claimed to have been on operating from Harwich. Had he perhaps heard the tale of the French marine painter Joseph Vernet being tied to a mast, like Odysseus, and borrowed the incident for an adroit bit of marketing?

In 1810, however, there was a witness to his fascination with atmospheric turbulence. Turner was staying with his friend Walter Fawkes at Farnley Hall in Wharfedale, North Yorkshire, when a storm barrelled over the hills. The painter was transfixed and stood in the doorway sketching. He called to his host’s son: ‘Hawkey! Hawkey! Come here! Come here! Look at this thunderstorm! Isn’t it grand? Isn’t it wonderful? — isn’t it sublime?”’ His sketchpad, the boy recalled, was the back of a letter. ‘He was absorbed — he was entranced.’ When the storm finally passed, the painter said: ‘There Hawkey, in two years you will see this again and call it Hannibal Crossing the Alps.’

Turner was true to his word. With brilliant sleight of hand and eye, this Yorkshire thunderstorm re-emerged as a life-and-death struggle in the high peaks and the dale-cropping sheep became the Carthaginian general and his army battered by terrifyingly malign swathes of rain and wind. Long before they came to face any Roman army, Hannibal and his troops had this maelstrom to contend with.

Like Turner, the German-born American painter Albert Bierstadt was prepared to endure innumerable hardships in his quest for raw Nature. In the mid 19th century, Bierstadt made a series of expeditions into the mountains of the American West. The bulk of the nation’s citizens hugged the coasts, so he was determined to show them the majesty of their native land. With a local guide and provisions packed on to mules, he headed for the Rockies west of Denver and sketched whatever he saw.

In one picture, A Storm in the Rocky Mountains, Mt Rosalie, 1866 — pictured at the top of this page — he depicted the hallucinatory scene that greeted him as he emerged from wet forests. With Turner’s word ‘sublime’ in his unconscious mind, he marvelled at clouds ‘so low that they were being torn and riven’ by the mountain points and broken formations driven ‘in rolling masses through the storm-drift’. This was virgin territory and it seemed to him as if the landscape was being formed from the storm itself. His tribute to the spot was not only the art, but the name he gave to the peak that towers above all: Mount Rosalie, after his wife.

Not every painter had to put themselves in danger to paint storms. When Henri Rousseau painted his celebrated Tiger in a Tropical Storm (1891), showing the big cat, teeth bared and in a lush jungle lashed by wind and rain, he claimed (or his supporters did) that he had witnessed such a jungle storm when serving as a regimental bandsman in Mexico. The truth, however, was more prosaic: Rousseau had never strayed from France and his tiger was based either on a specimen in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris or from book illustrations.

Nevertheless, the painting’s alternative title, Surprised!, has a double meaning; it covers both the shock of the prey about to be attacked, but also the feeling of the tiger itself as the storm breaks about it. As the leaves shake, the rain hammers at the foliage and lightning slices the sky, the animal’s teeth could be chattering as much as relishing the prospect of meat.

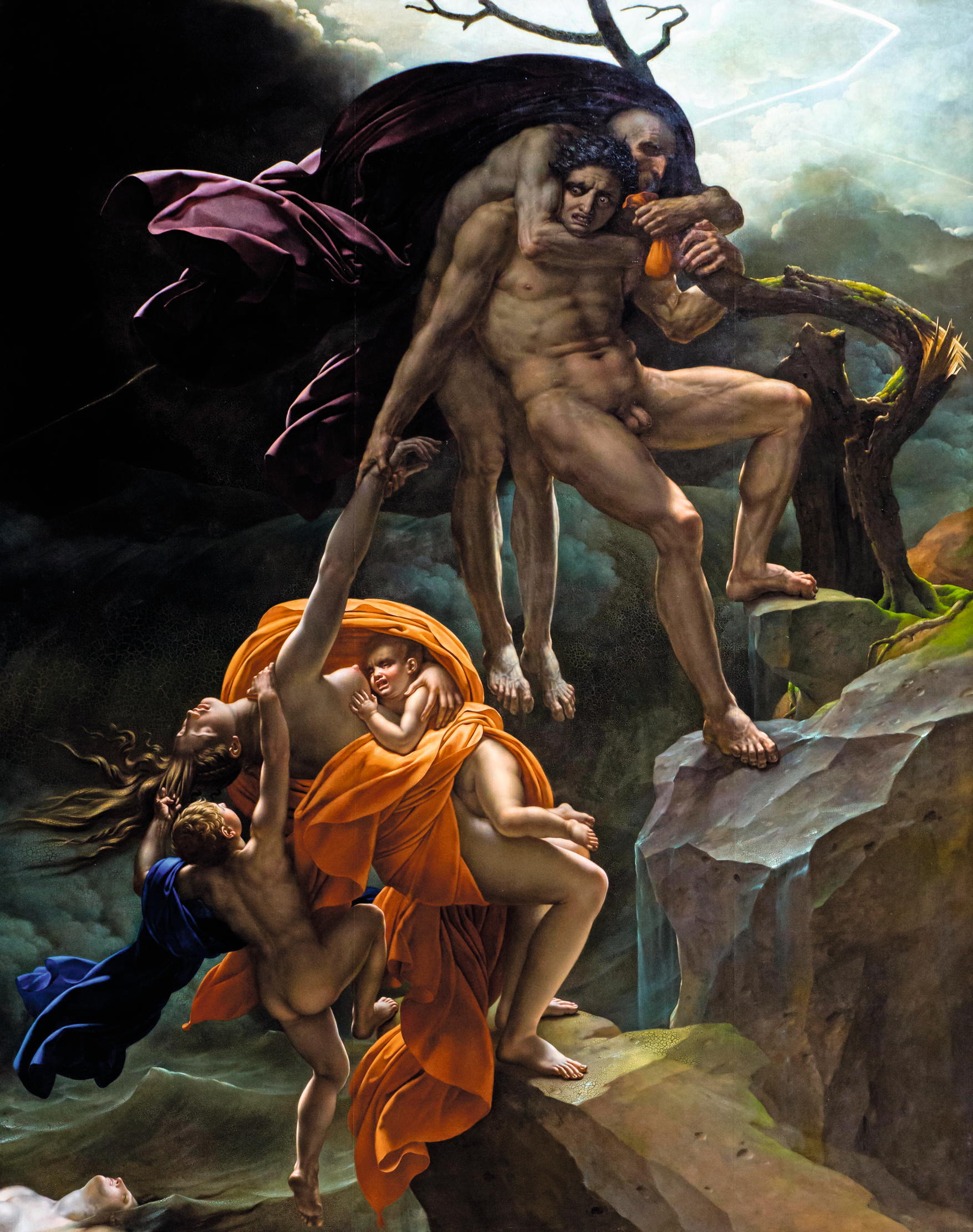

In 1806, Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson triumphed at the Salon, the annual showcase of French art, with his Scene of a Deluge. Here is no jungle storm, but a human tragedy that stopped the crowds where they stood and thrilled them with its King Lear-like squall and moment of extreme peril. In it, a man clutches on to a tree at the edge of a cliff, he carries his own father on his back and desperately tugs his wife, as her weight and that of the two children clinging to her pull her backwards to their doom. The ferocity of the elements thrashes their cloaks about them and lightning rends the sky. Although it was meant to bring the Biblical Flood to mind, the picture is really the equivalent of a still from a disaster film.

In England, Girodet’s younger contemporary John Martin made a hugely successful career with his enormous paintings of stormy destruction, such as The Great Day of His Wrath, 1853. Here, a raging red sky and boiling clouds presage the Apocalypse, with the minute human figures helpless as divine retribution causes chasms to open beneath them and rocks tumble down on to them. Nature has here become a cauldron from which there is no escape. As the great storm that struck Britain in 1987 reminded us of our impotence in the face of Nature, so Martin’s pictures stressed to the Victorian viewer their small and fragile place in the world.

Among the innumerable paintings of storms, however, there is one — one of the very greatest — that has never been explained. In about 1508, the Venetian artist Giorgione painted The Tempest, a small canvas that shows a woody patch of land and a bridge on the edge of a village. In the foreground are a soldier and a naked woman suckling her child. The light is otherworldly, grey clouds bubble and the sky crackles with electricity. There is no clue as to the relationship between the figures — they could be mythological, allegorical, vaguely biblical — and what is going on in the painting has been an enigma for more than five centuries. Storms usually bring nothing but destruction; here, however, there’s magic in that supercharged sky.

The wave that swept the world: Hokusai's The Great Wave off Kanagawa

When, in 1831, the Japanese woodcut artist Hokusai came to make his The Great Wave off Kanagawa, he stuck to the shore. The picture, in which three boats transporting fish across Tokyo Bay are about to be swamped by a towering rogue wave, is one of the most famous images in art. It comes from Hokusai’s series ‘Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji’ and was made when he was already 71 (he believed he got better with age and described himself as ‘old man crazy to paint’).

The mountain is there in the distance, but it is the foreground action that dominates, as the wave, which experts have calculated as being nearly 40ft high, prepares to devour the boats. Its frothing crest has formed into claws and its concave curve has become a gaping mouth to swallow the fishermen up. Although the storm itself has blown through, leaving the sky a leaden grey, its winds have raised this sea monster. ‘From the age of six,’ said Hokusai, ‘I had a passion for copying the form of things’; here is that intense observation in action. Van Gogh, one of many Western artists to be influenced by Japanese woodcuts, described the picture simply as ‘terrifying’.

In Focus: How Italy inspired JMW Turner

Mary Miers considers how the country that fascinated Turner from youth shaped his artistic vision.

My Favourite Painting: Nick Hewer

Countdown presenter Nick Hewer is inspired by a recent trip to Japan to choose this iconic painting.