The art of the seaside

Open skies, shifting clouds and the golden expanse of the beach have inspired artists from John Constable to Antony Gormley, but the sun-bathing throngs have proved a rather less popular subject, as Michael Prodger discovers.

Brighton may have been George IV’s favourite seaside haunt — the town he made fashionable — but it wasn’t John Constable’s. ‘Brighton is the receptacle of the fashion and off-scouring of London,’ the painter wrote, with a curled lip, to his friend Archdeacon Fisher in 1824. The emotions summoned up by its vistas of the sea were, he said, ‘drowned in the din and tumult of stage coaches, gigs, flys, &c. and the beach is only Piccadilly or worse by the sea-side’.

He then went on to list its denizens: ‘Ladies dressed and undressed; gentlemen in morning-gowns and slippers, or without them or anything else… footmen, children, nursery-maids, dogs, boys, fishermen, and Preventive Service men with hangers and pistols.’ As if all this weren’t bad enough, the resort was further tarnished by the miasma of rotten fish and the sight and sound of ‘hideous amphibious animals, the old bathing-women’. For the painter, the benefits of sea bathing, salt air and an inspiring expanse of empty sea and sky came at a cost.

When Constable turned to paint the beach, which he did many times, he removed as much of this noisome throng as possible and concentrated instead on the waves, scudding clouds and working boats bent over by the breeze. Holidaymakers do sometimes feature, but they tend to be blobs of paint, there to give a little bit of verticality to the broad horizontals of beach and sea. Or to poke fun at: in his 6ft-wide Chain Pier, Brighton, 1826–27, a pair of female promenaders battle the wind, shawls pulled tight and umbrella up, in their determination to benefit from the ozone-rich air come what may.

Usually, however, Constable’s figures are incidental; Nature was his real subject. What the seaside gave to him — and to numerous other painters, from J. M. W. Turner to James Abbott McNeill Whistler — was uninterrupted skies and shifting cloud formations. Constable studied the clouds as an entomologist studies insects, marvelling in their innumerable shapes. In a small oil sketch, he shows a rainstorm breaking at sea with great arcs of black and grey paint sweeping apocalyptically down; in other rapid notations, made at Hove or Weymouth, he depicts benign clouds swelling like soufflés, with their edges catching the sun as they fluff up.

Constable was only one of many painters intrigued by the seaside’s dual aspect; a place where raw Nature and rowdy humanity met. Nor was he the only painter who preferred his beaches empty of holidaymakers. On his return from the First World War, Paul Nash took himself to Dymchurch, on the Kent coast, to hunker down and try to slough off the experience of the trenches. His self-treatment meant painting his way out of trauma, which he did, eventually, by making a series of bleak pictures of the long sea wall that edges the coastline there. This seaside is no place for kite flying and crabbing, but a scene of conflict, where the sea and the wall are in relentless opposition — implacable forces, battering and resisting — and seem a direct reflection of his own inner conflict.

Decades later, Nash’s simplified images were pared-back even further by Wilhelmina Barns-Graham. In 1940, ‘Willie’, as she was known, had joined the Modernist artists who had gathered in St Ives in Cornwall — Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth among them. There she came to believe that a ‘painting is a pattern, and paintings should be just as good upside down, sideways, in a looking glass…’ and unpeopled beaches were a perfect motif. In West Sands (St Andrews), July, 1981, she showed exactly what she meant — a picture that, when seen the right way up, shows the rippling eddies of sand exposed when the tide has gone out; turn it upside down, however, and what you get are gentle hills above pink water.

St Ives was one of several coastal towns around Britain that, from the 1880s to the 1930s, drew artists with their picturesqueness and their time-honoured customs. As much of the country became ever more urban and industrial, places on the land’s edge, such as Newlyn, Lamorna, Staithes and Cullercoats, became artists’ colonies offering a form of authentic life, unchanged over the centuries, that was becoming ever harder to find. Stanhope Forbes, Laura Knight and Samuel John Lamorna Birch painted fisherfolk, working quaysides and coves lapping with brilliant blue water. Although the artists were well aware of the hard reality and poverty of the fishing villages, they conjured up a romanticised version for a public who might come to visit, but would never work or live in such places.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Some artists, however, were more honest. From the 1890s, Philip Wilson Steer was a regular visitor to Walberswick on the Suffolk coast and painted it as a thriving summer tourist spot. His pictures, heavily influenced by the still-novel Impressionist style imported from France, are full of visitors relaxing in the light of an unending summer’s day. Children play on the water’s edge, young girls in muslin frocks run on a jetty, some gentle wooing takes place in the golden hour. Even as these harmless scenes unfold, Steer wraps them in a dreamy nostalgia — this is how summer holidays are meant to be.

By 1966, when William Roberts came to paint The Seaside, a picture stuffed full of sunbathers and squirming children, Steer’s well-mannered beaches had turned boisterous. The decorous clothing and broad-brimmed hats had been swapped for bikinis and suntan lotion and the willowy forms of the holiday makers morphed into monumental figures, as if carved by Henry Moore. The sands are still golden and the sun still shines, but the beach is now democratised and occupied by the day-tripping descendants of Constable’s kiss-me-quick Brighton crowd.

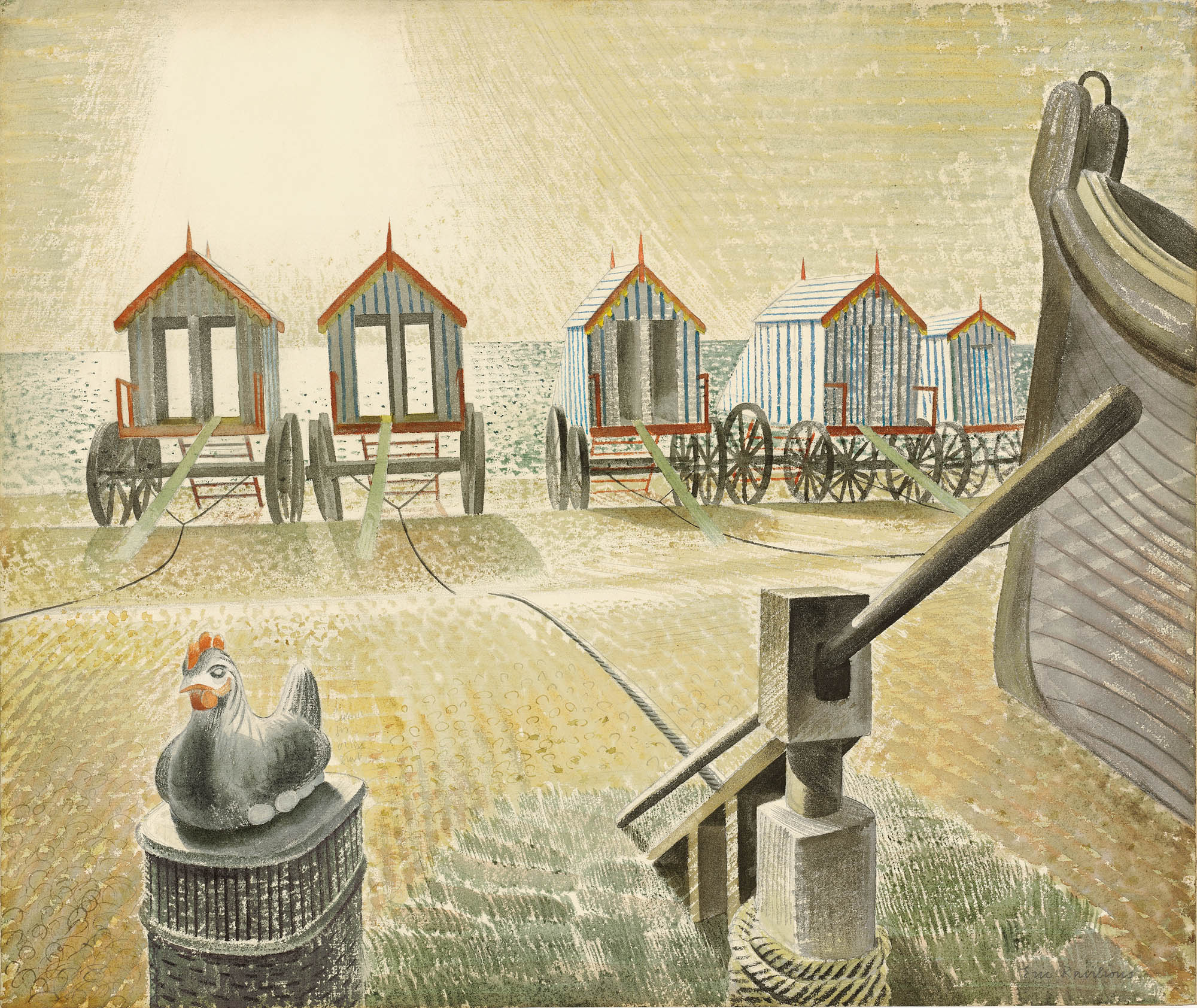

Back in 1938, only a few miles from where Steer had painted, Eric Ravilious found a way of including people by not including people. When he painted the beach at Aldeburgh, he showed the bathing huts the frolickers had just left; these jolly wheeled cabins stand guard on the beach in a row, but of their occupants there is no sign. Ravilious was adept at discerning the patterns in landscape and the poetry of abandoned machinery, but people are messy creatures who would break up the rhythms he found, so he did away with them. His is a ghost beach, with the sounds of splashing and laughter still trembling in the air as Nature comes to reclaim the scene. When the war started a year later, Ravilious carried on painting beaches and simply replaced the bathing huts with military hardware and barbed wire — the end of innocence had come.

Some 60 years later, the frisson that Ravilious discerned was made more tangible by Antony Gormley. Another Place, first exhibited in 1997, comprises 100 life-size cast-iron figures, straight backed, arms by their sides, facing out to sea. As the tide comes in, they are gradually submerged; as it recedes, they appear — from drowning to being reborn from the waves in an endless cycle. In 2005, the figures were set along a two-mile stretch of Crosby Beach, just north of Liverpool, where they stare across the water, a reference, Mr Gormley says, to the Irish diaspora, so many of whom sailed for America from Liverpool. The statues are taken from a cast of the sculptor’s own body and, over time, the iron has rusted and become encrusted with barnacles and seaweed, just as he himself has aged. Nevertheless, like figures from myth — as holidaymakers play among them and pose alongside them — these immobile forms will keep their haunting vigil until nothing of them is left.

For other artists, the sense of infinity offered at the water’s edge spurred them on. John Everett Millais, for example, in his famous The Boyhood of Raleigh, 1870, sits his adventurer-to-be with a companion by a low sea wall as they listen enthralled to the tales of a Genoese sailor. As this picturesque figure points into the distance, the two boys’ imaginations follow his finger out to sea and dream of adventure, the Spanish Main, treasure and glory. In this moment, a Devon beach ceases to be a playground and becomes a stepping-off point into the future. At one edge of the painting is Raleigh’s toy boat, at the other a dead toucan and a feathered hat from the Americas — here is the journey towards fame that the swashbuckling mariner will make in a few short years’ time.

The seaside has long been all things to all painters — a place to watch humanity or escape from it, to capture both hot sun and fleeting squalls, to return to childhood or dream of alternative futures, to flinch from the waves or yearn for them, to breathe in stillness or contemplate infinity. A strip of beach is where two elements touch and it has always brought together the different elements of an artist’s minds. And of course, water and clouds are perfect for paint.

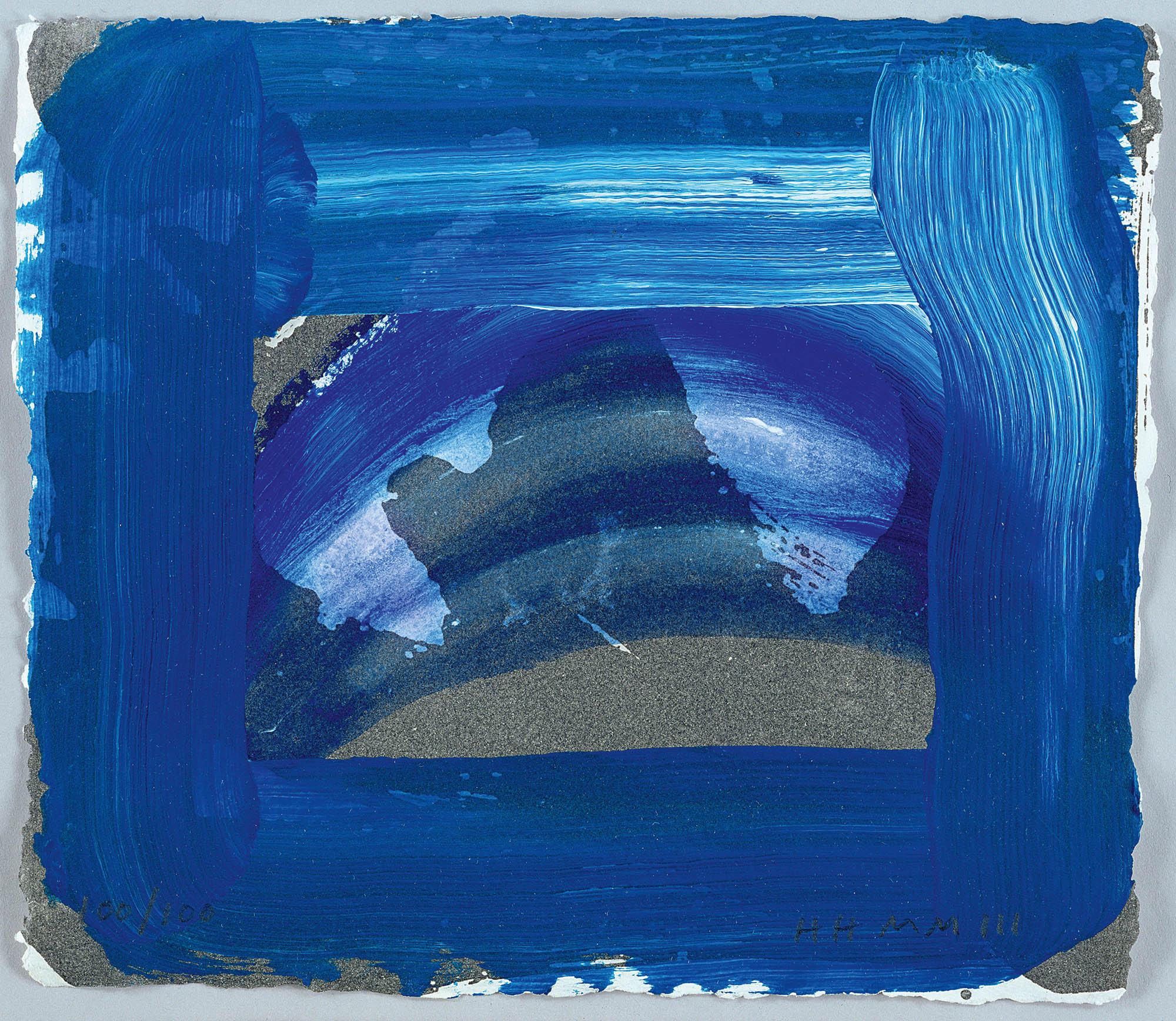

The big blue: the shore in abstract art

It was the abstract artist Howard Hodgkin who perhaps best caught the universal dream of the seaside. Over the years, he worked on a series of paintings with the word ‘sea’ in the title (as with Sea, 2002–03, above). His method was seemingly simple: a brush laden with a generous dollop of rich blue dragged on canvas or panel in a few visible and luscious strokes.

That was all it took to make a fully formed picture in which, eyes closed, you can taste salt, sense heat and hear with your inner ear waves and sea breezes. The paintings don’t show a place or a scene, but rather capture a recollection of a moment and an atmosphere. In doing that, he painted each and every seaside of each and every one of us.

Credit: ©David Hurn / Magnum Photos

In Focus: The photographer obsessed with why we all like to be beside the seaside

A summer of rediscovering the traditional British seaside holiday

With foreign travel still uncertain, millions of us are set to holiday in Britain this year — and that is something

Credit: Visit Great Yarmouth - www.great-yarmouth.co.uk

Great Yarmouth: Endless skies, endless rides and the evolution of the Great British seaside holiday

The British seaside has had a memorable year with more people holidaying in the UK than there have been for

Revealed: How to stop seagulls from stealing your chips

Seagulls begging for food are the scourge of many a day at the British seaside — and where there is