The ancient mapmakers who shaped the world as we still see it centuries later

The desire to chart the world around us is an impulse as old as time and some map-makers’ efforts have an astonishing longevity, reveals Matthew Dennison.

In 1676, London publishers Thomas Bassett and Richard Chiswell had a success on their hands. Half a century after first publication, they reissued in a single volume two atlases by John Speed: The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine of 1612 and A Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World (1627).

Speed’s maps were of surpassing beauty, ornamented with decorative strapwork and flowing calligraphy by Dutch engraver Jodocus Hondius, their broad margins featuring medallion-shaped, bird’s-eye views of large and small towns, from Edinburgh to Radnor, or images of key buildings, including palaces and cathedrals, coats of arms of noblemen and university colleges and distinctive, flattened-perspective town plans.

In his foreword, Speed had been at pains to assure his readers of the thoroughness of his research, so extensive, he claimed, that he had had ‘small regard to the bewitching pleasures and vain enticements of this wicked world’. His readers were convinced. Speed’s Theatre would remain in print until the final quarter of the 18th century and, on his death in 1629, Speed’s success as a cartographer accounted for healthy bequests to all of his 18 children who survived him.

For his contemporaries, Speed’s maps were not, of course, primarily decorative. As were many early maps, according to Kristina Chan, director of Plaintiff Press (who is currently producing prints based on a late-15th-century world map by Renaissance Italian humanist Francesco Berlinghieri), Speed’s annotated representations of land masses from the British Isles to Bermuda were ‘documents concerned with trying to read the world and make sense of it’.

In a pre-digital age, before the scientific revolution of the Enlightenment and western explorers’ voyages of discovery to Antarctica and much of the Pacific, map-makers sought to order and explain both the unknown and the familiar, expanding readers’ understanding of places near and far and, in Speed’s 17th-century England, encouraging an increasingly outward-looking mindset that would play its part in subsequent colonisation.

Yet, even in 1612, the desire to map the world was not a new impulse. A mammoth tusk discovered in Moravia in the 1960s, engraved with the course of a river, valleys and a mountain, points to rudimentary cartography at least 25,000 years ago. A diminutive clay tablet from the ancient city of Babylon, incised with stylised depictions of islands identified in cuneiform text as lying ‘beyond the flight of birds’, predates the birth of Christ by half a millennium. Medieval mappae mundi (‘charts of the world’) recorded aspects of the inhabited world, in some instances, such as the Hereford Mappa Mundi, in a specifically Christian framework, with Jerusalem at the map’s centre. In each case, to modern eyes, inaccuracies and distortions are clear; behind each is the same desire to understand aspects of the world from which they sprang.

Early maps are frequently labelled: written as well as pictorial details indicate their creators’ aim of quantifying or elucidating the universe. A Muslim scholar-cum-cartographer known as Muhammad al-Idrisi, commissioned by Roger II of Sicily in the middle of the 12th century, embellished some 70 maps with descriptions culled from travellers’ tales. Al-Idrisi did not confine himself to information about landscape or climate: he included political, cultural and even socio-economic nuggets. For Miss Chan, details of this sort are what make early maps so compelling: ‘They reveal a world still trying to figure out edges and boundaries, much as, in different ways, we are today. There’s humanity and relatability in these maps.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

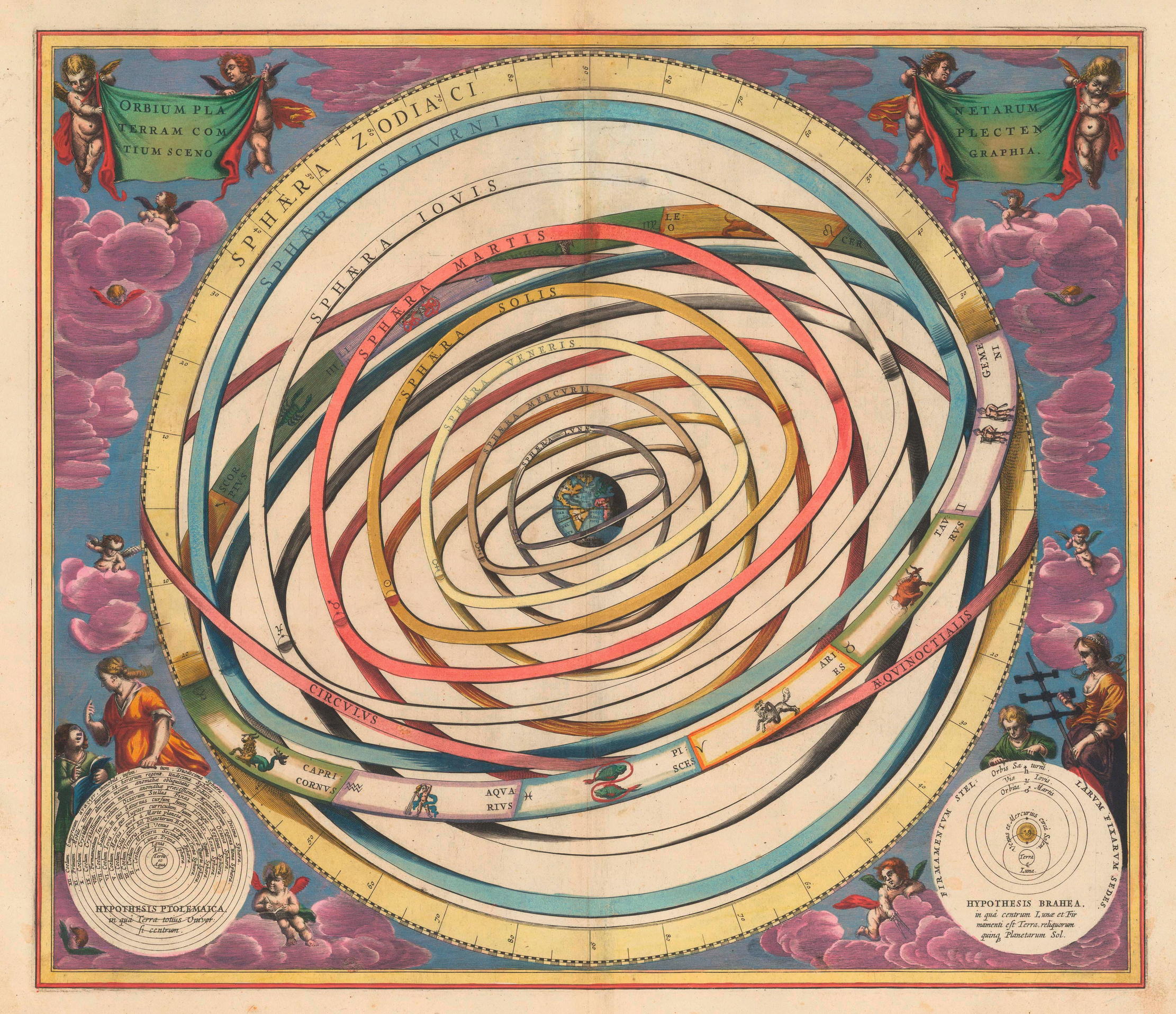

Miss Chan’s current project is concerned with items in the Sunderland Collection of atlases, terrestrial and celestial maps and globes dating from 1200 to the 19th century. Items span a series of developments in map-making techniques, from woodblock printing and metal-plate engraving to later, less costly lithography. ‘When you read an old engraving plate, you can see the engraver come to life — lines are deeper where they have worked with confidence, more shallow lines reveal the engraver’s hesitation and perhaps the limits of their knowledge,’ she enthuses.

In the printed reproductions of Berlinghieri’s World Map that Miss Chan is now colouring by hand, she has endeavoured to preserve these signifiers of human handiwork and, in doing so, to capture traces of the Renaissance worldview that was itself indebted to the ground-breaking work of 2nd-century Greek astronomer and mathematician Claudius Ptolemy. Ptolemy’s eight-volume Geography, first printed in Latin with maps in 1477 and again in 1513, gave Renaissance scholars detailed descriptions of methods of cartography, apparently with a view to facilitating accurate map-making. Ptolemy divided the world into zones based on climate; he indicated precise means of identifying locations using a coordinates system of longitude and latitude. Although he was mistaken in positioning the earth at the centre of the universe, he understood that the world was not flat. In doing so, he set a challenge for every subsequent map-maker.

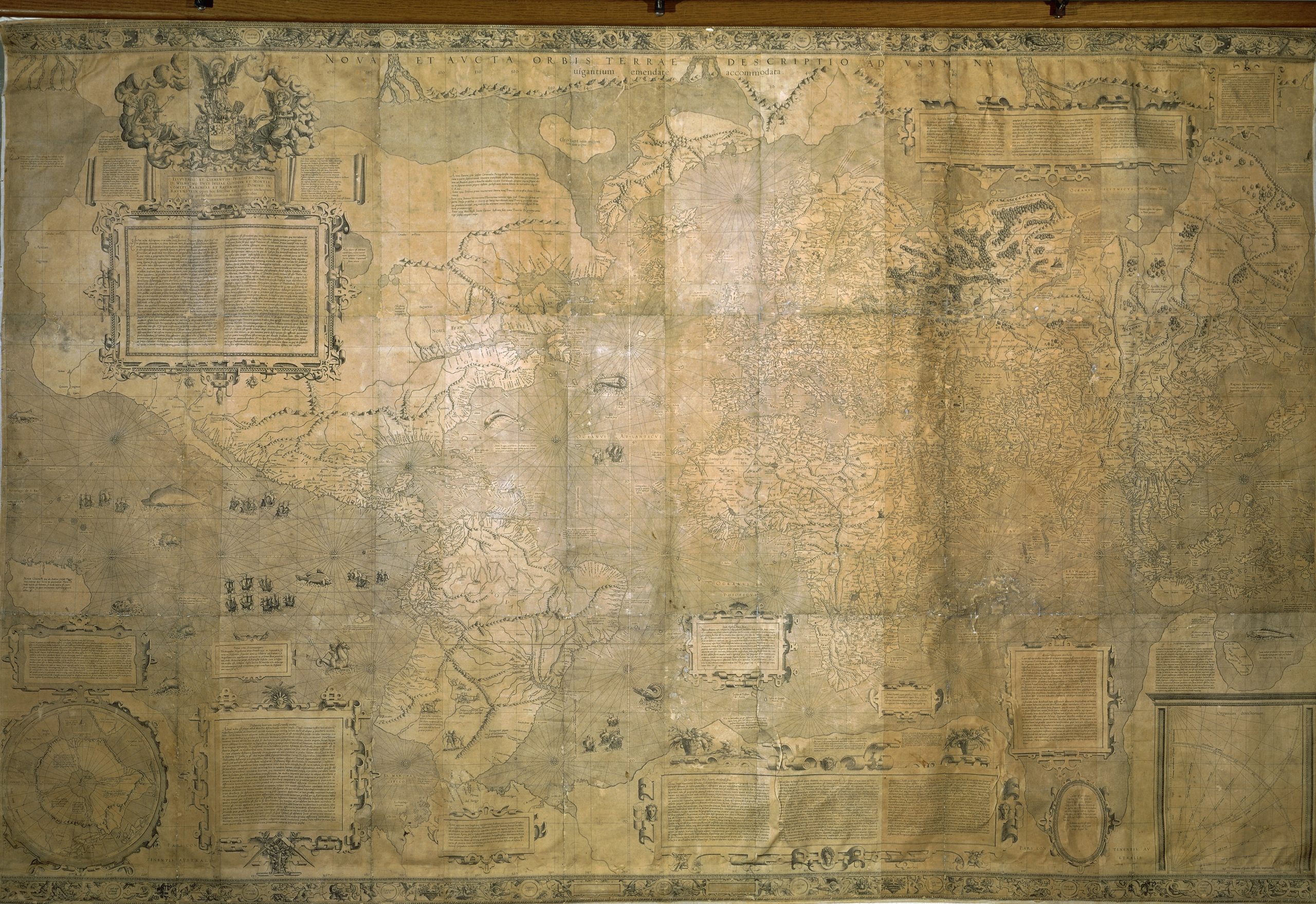

Among those who took up the gauntlet were Joan Blaeu, official cartographer to the Dutch East India Company, and Flemish map-maker Gerardus Mercator, described by a 16th-century biographer as a man of ‘mild character and honest way of life’. Trained as an engraver and calligrapher, influenced by the work of globemaker Gemma Frisius and French mathematician Oronce Fine — who, in 1531, explained his ‘representation of the entire world’ as ‘laid out on a plane in the form of a double human heart; of which the left comprises the northern part and the right the Southern part of the World’ — in middle age, Mercator evolved a clear, if not fully accurate, means of depicting the spherical earth in two dimensions.

‘Mercator’s Projection’ was published in 1569. Its model of a flattened globe crisscrossed by lines of longitude and latitude, intersecting at 90˚ angles, proved a key influence on subsequent map-making and a familiar staple of schoolrooms for centuries.

Mercator’s is not the only map to have achieved a degree of longevity unanticipated by its creator. In the 1950s, at the Great Barrier Reef off Australia’s north-east coast, a young David Attenborough used charts compiled by Capt Cook almost two centuries earlier, when, in the summer of 1770, Cook’s ship Endeavour collided with what he first took to be rocks, but which turned out to be a coral bank.

Early in his career, on voyages to Newfound-land and Quebec, Cook had demonstrated his skill as a surveyor. Over time, particularly on his Pacific voyages, he successfully partnered his knowledge of land-surveying techniques with a talent for nautical mapping. The results were detailed charts of the coast of New South Wales, as well as maps of the coastline of New Zealand and, on another voyage, the north-west coast of North America.

Echoing maps before and since, Cook’s charts sought to record in as accurate and readily comprehensible a form as possible the topography of the places he encountered and ‘discovered’. Later updated, his charts remain rich sources of information, increasingly for environmentalists and conservationists.

For centuries, maps have been valued — by travellers, explorers, adventurers, colonists, collectors and, on occasion, ne’er-do-wells. The 17th-century English buccaneer Bartholomew Sharp rejoiced in the maps he plundered from a Spanish ship, El Santo Rosario, in the summer of 1681. ‘I took a Spanish manuscript of prodigious value,’ he noted. ‘It describes all the ports, harbours, bays, sands, rock and rising of the land… They were going to throw it overboard, but by good luck I saved it.’ Sharp’s stolen maps were undoubtedly invaluable for this rapacious privateer. As did other maps of the time, they combined artistry with adroit draughtsmanship and the promise of brave new worlds. Little wonder, then, as Sharp explained, that ‘the Spanish cried when I got the book’.

For details of the prints based on Berlinghieri’s 1482 World Map, in the Sunderland Collection, handmade by Kristina Chan of Plaintiff Press, visit www.oculi-mundi.com

The world's first road atlas

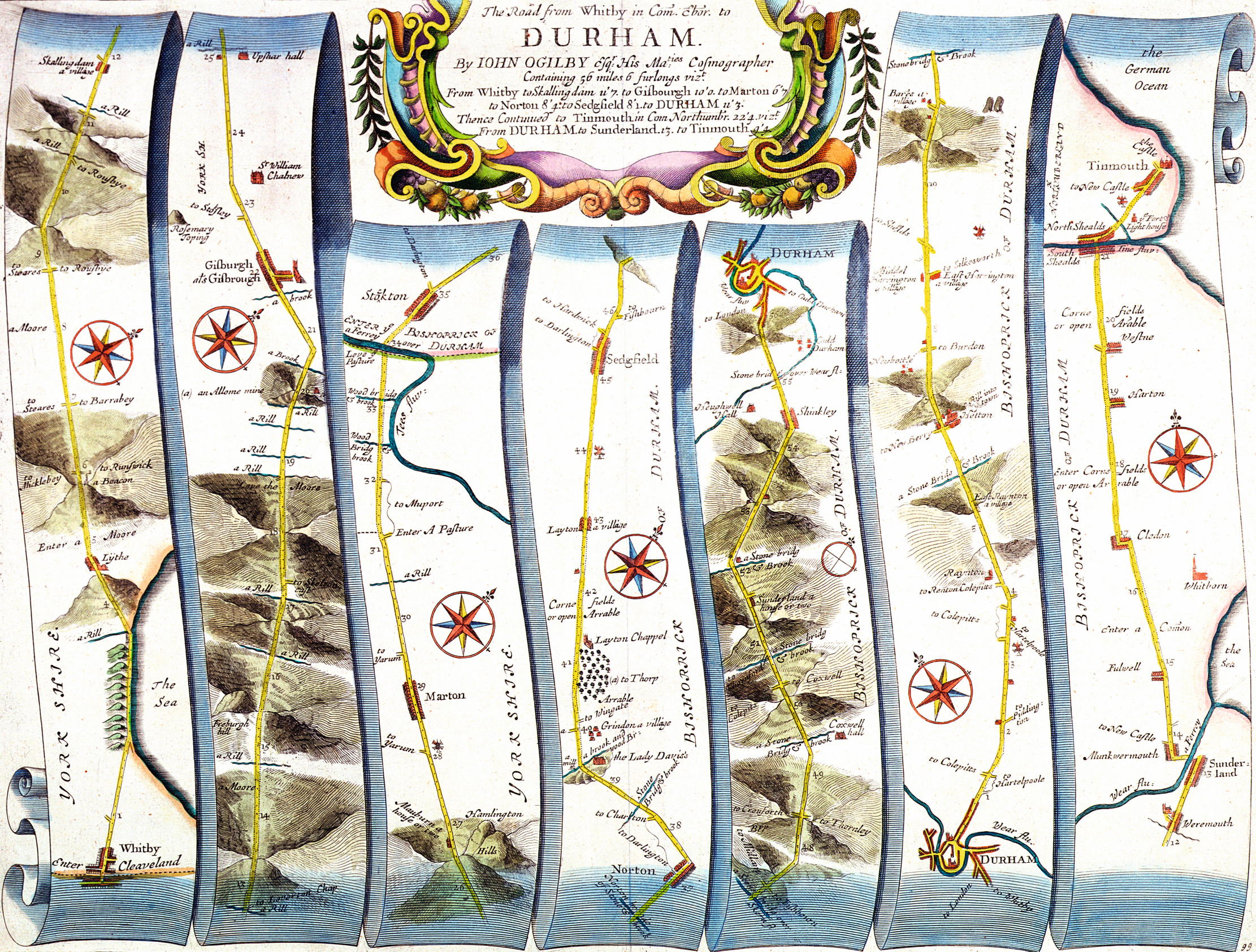

The world’s first road atlas, a sumptuous collection of road maps created by an ageing Scottish former-dancing-master-turned-secret agent, was published in 1675.

The Britannia of septuagenarian John Ogilby, cosmographer to Charles II, featured a series of maps of routes in England and Wales, depicted in a distinctive vertical scroll format by engraver Wenceslaus Hollar.

Ogilby made use of a standardised scale to increase the usefulness of his maps. He also eliminated all but key details of the routes depicted, including, for example, bridges, rivers, ‘A Great Mountaine’, ferries, heath, ‘arrable’ and the most prominent buildings in a vicinity, among them churches and the seats of local gentry.

Pictures: Getty; Alamy; Bridgeman images; The Stapleton Collection/Bridgeman Images; The Sunderland Collection/Kristina Chan/Plaintiff Press, www.oculi-mundi.com; Oculi Mundi; Iberfoto/Bridgeman Images

Credit: Leonardo da Vinci

The awkward questions that still need answering about Da Vinci's $450m Salvator Mundi

The dust has now settled following the $450 million sale of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi. But there are still

Credit: Alamy

Jason Goodwin: The quiet miracle of 'paths of will', where we shrug off authority and trust the people who have gone before

Jason Goodwin takes a moment to consider those little paths which spring up almost of their own accord, the muddy

What's the difference between a labyrinth and a maze?

You may never have thought to ponder what distinguishes a labyrinth from a maze. But as Martin Fone explains, it's

-

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter Weekend

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter WeekendAsparagus has royal roots — it was once a favourite of Madame de Pompadour.

By Melanie Johnson

-

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtower

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtowerOn Cliff Hill in Gorleston, one home is taller than all the others. It could be yours.

By James Fisher